Government jobs are often allocated based on bribes and patronage. How does this process work, and can this lead to good outcomes?

In many developing countries, obtaining government jobs through paying bribes and political connections is thought to be ubiquitous. The conventional wisdom has been that such practices lead to the hiring of low-quality government workers (Sukhtankar and Vaishnav 2016, Muralidharan 2015). This may cause serious and long-run harm since government workers often have long careers and influence many other individuals through their actions. For example, if a low-quality teacher is hired due to bribery, this could have a negative impact on not only their current students, but on the hundreds of students they will eventually teach.

Aside from a few qualitative accounts (Wade 1985), almost nothing is known about how corruption in hiring for government jobs works in practice. There is also an absence of evidence on more complicated questions such as whether it has negative consequences. Some recent papers have shown that an individual’s personal connections help getting hired for government jobs, and that such patronage-based hiring is related to worse outcomes from hires (Colonnelli et al. 2017, Fafchamps and Labonne 2017, Xu 2017).

Unanswered questions

- In contemporary developing countries, do people pay bribes for jobs, and if so, how much?

- How are corrupt hiring decisions made, given that there may be many politically connected applicants or applicants offering bribes?

- Do corrupt hiring systems have a negative impact on service delivery?

- If so, how should we design anti-corruption measures targeted at hiring processes?

The study

In a recent paper, I collect data to answer these questions (Weaver 2017). The data come from a hiring process for mid-level manager positions in a developing country bureaucracy. Each hired manager supervises 15-20 health workers who deliver primary health care services in rural villages. I collect detailed data on both the hired managers and the health workers they supervise, including bribe offers by those who applied for the job and payments by those who were hired.

How do these markets work?

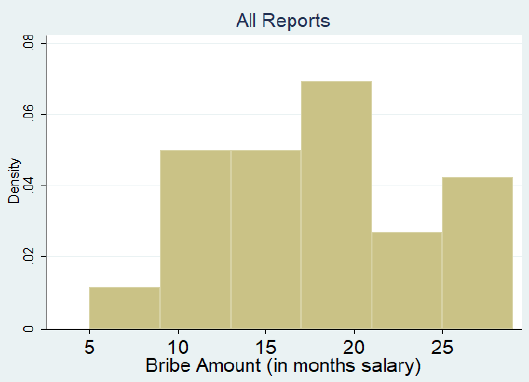

- All hires paid large bribes to get their jobs, averaging 17 months’ salary in the position (Figure 1). While enormous, these bribes are less than have been observed in other cases (e.g. Kristiansen et al. 2006).

- The hiring process functioned in a manner very similar to an auction. Many applicants offered bribes of differing sizes to the individuals responsible for making hiring decisions.

- Some applicants tried to use political connections to influence the hiring decision.

Figure 1

Since I observe usage of political connections, bribe offers, and other characteristics of the applicants, it is possible to figure out exactly how hiring decision were made. Hiring decision were based on three things:

- The size of the bribe offer

- The applicant’s political connections

- The education of the applicant

However, the size of an applicant’s bribe offer is by far the most important factor, determining the majority of hiring decisions. Understanding that the process works as an auction primarily based on bribes is useful in devising anti-corruption strategies.

The impact of corruption

Hiring high-quality individuals for this job (as a mid-level government manager) matters a great deal for delivery of public services. I find that reassigning a frontline worker from being supervised by a median quality manager to one in the top 15% of managers leads to large improvements in performance. This includes a 7.6% increase in deliveries at a hospital and a 15% increase in newborn check-ups conducted. Whether corrupt hiring leads to worse quality managers being selected will clearly matter.

To determine the impact of the corruption, I create a method to compare the actual hires, under the corrupt system, to those who would have applied and been hired under more standard hiring methods, such as selecting the highest scorers on a standardised test. Surprisingly, the corrupt system performs quite well when compared to three merit-based methods of hiring.

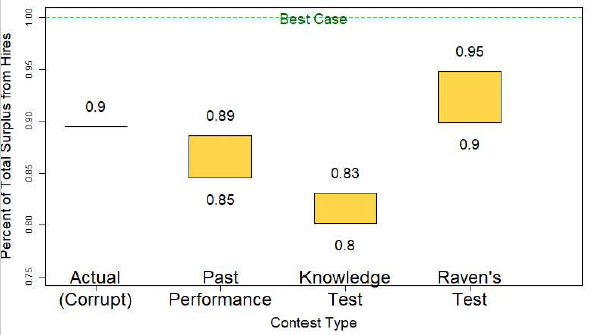

Figure 2 plots the quality of hires under each of the system, where 0 is the worst value and 1 is the best. Actual hires are significantly better than hires based on a knowledge-based test, and weakly better than hires based on past performance in a lower level role. However, the actual hires are not the best possible hires. Hiring based on a Raven’s Matrices test, a test of problem-solving ability, yields a superior set of hires.

Figure 2

These findings are counterintuitive, but have a simple explanation. Hiring based on bribes selects those who are wealthy and have a high desire for the job (willingness to pay). Both wealth and willingness to pay are strongly positively correlated with being a good manager in this context, which causes corrupt selection to lead to the hiring of good managers. Some of the other selection methods, such as the health knowledge test, are less strongly related to performing better as a manager. As a result, hires under those systems are not of as high a quality.

The study also discusses the types of jobs in which corruption will lead to more or less negative outcomes. Corruption in hiring for many types of jobs will be similar to this case and need not lead to negative outcomes. However, it will lead to bad outcomes for other types of jobs, such as police officers or tax collectors. This finding is related to whether there are many opportunities for corruption in the job in question. In jobs where there is high scope for corruption, more corrupt individuals will be willing to pay larger bribes, and thus be selected.

Policy implications

- Higher-quality mid-level managers led to large improvements in service delivery. Focusing on hiring processes, especially for managerial positions, is a promising method for reforming developing country bureaucracies. In this case, skills related to problem-solving ability and education were the most important for managerial performance.

- The effects of corruption in hiring are not universally good or bad, but will depend on the context in a predictable manner. In this case, corruption led to good outcomes, but I show that for other types of jobs, this need not be the case. Determining the positions in which corruption will cause greater or lesser distortions is useful in allocating limited anti-corruption resources.

- Recognising that contemporary corrupt job markets function like an auction is useful for effectively designing anti-corruption measures.

- A companion project (Weaver forthcoming) shows that standard ways of cracking down on corruption can backfire and worsen outcomes when applied to hiring processes. There is therefore a need to look into these contexts to design better hiring systems.

References

Colonnelli, E, M Prem and E Teso (2017), “Patronage in the Allocation of Public Sector Jobs”, Working Paper.

Fafchamps, M and J Labonne (2017), “Do Politicians’ Relatives Get Better Jobs? Evidence from Municipal Elections”, The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 33(2): 268-300.

Kristiansen, S and M Ramli (2006), “Buying an income: The market for civil service positions in Indonesia”, Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs 28(2): 207–233.

Muralidharan, K (2015), “A New Approach to Public Sector Hiring in India for Improved Service Delivery”, UC San Diego, NBER, NCAER, and J-PAL Working Paper, Brookings-NCAER India Policy Forum.

Sukhtankar, S and M Vaishnav (2015), “Corruption in India: Bridging Research Evidence and Policy Options”, Brookings-NCAER India Policy Forum.

Wade, R (1985), “The market for public office: Why the Indian state is not better at development”, World Development 13(4): 467–497.

Weaver, J (2017), “Jobs for Sale: Corruption and Misallocation in Hiring”, Working Paper.

Weaver, J (forthcoming), “Designing Hiring Systems: Theory and Empirical Evidence”, Working Paper.

Xu, G (2017), “The Costs of Patronage: Evidence from the British Empire”, Working Paper.