A household’s access to the urban sanitation network can have a significant impact on whether it pays its taxes

One of the most critical components to successful development policy is the ability of the state to collect tax revenue and use these resources to provide adequate public goods and services (Besley and Persson 2013, Haq et al. 2020). In developing countries that struggle to provide universal basic services, the “social contract” - where citizens pay taxes in exchange for the state providing these services – can break down and lead to a vicious cycle of households not paying taxes due to the perceived failure of the state (Castro and Scartascini 2015, Okunogbe 2021, Weigel 2020). This is turn leads to lower tax revenue and an inability to improve public goods provision, further eroding citizen’s incentive to pay taxes.

One of the most basic services that the state provides is access to improved water and sanitation (WASH). Despite the large welfare gains to building and maintaining a sewer network – an estimated 1,656,000 global deaths each year are caused by lack of improved sewers (Troeger et al. 2018) – a large share of the population in developing countries live without it (Duflo et al. 2012). Moreover, WASH providers are facing increasing budgetary constraints as financial support from governments dwindle, potentially jeopardising the 2030 UN Millennium Development Goal of reaching universal WASH coverage (World Bank 2022).

Given how salient improved sanitation services are to citizens, it is likely that the lack of WASH services contributes to the equilibrium of high tax delinquency and low service provision observed across the developing world. For policymakers interested in increasing the state’s capacity to raise tax revenue and improve welfare, understanding the degree to which citizens respond to the (lack of) basic WASH services is of first order importance. However, the non-random structure of sewer networks makes disentangling the impacts of WASH take-up of tax compliance difficult for the researcher.

Property taxes and sanitation: The case of Manaus, Brazil

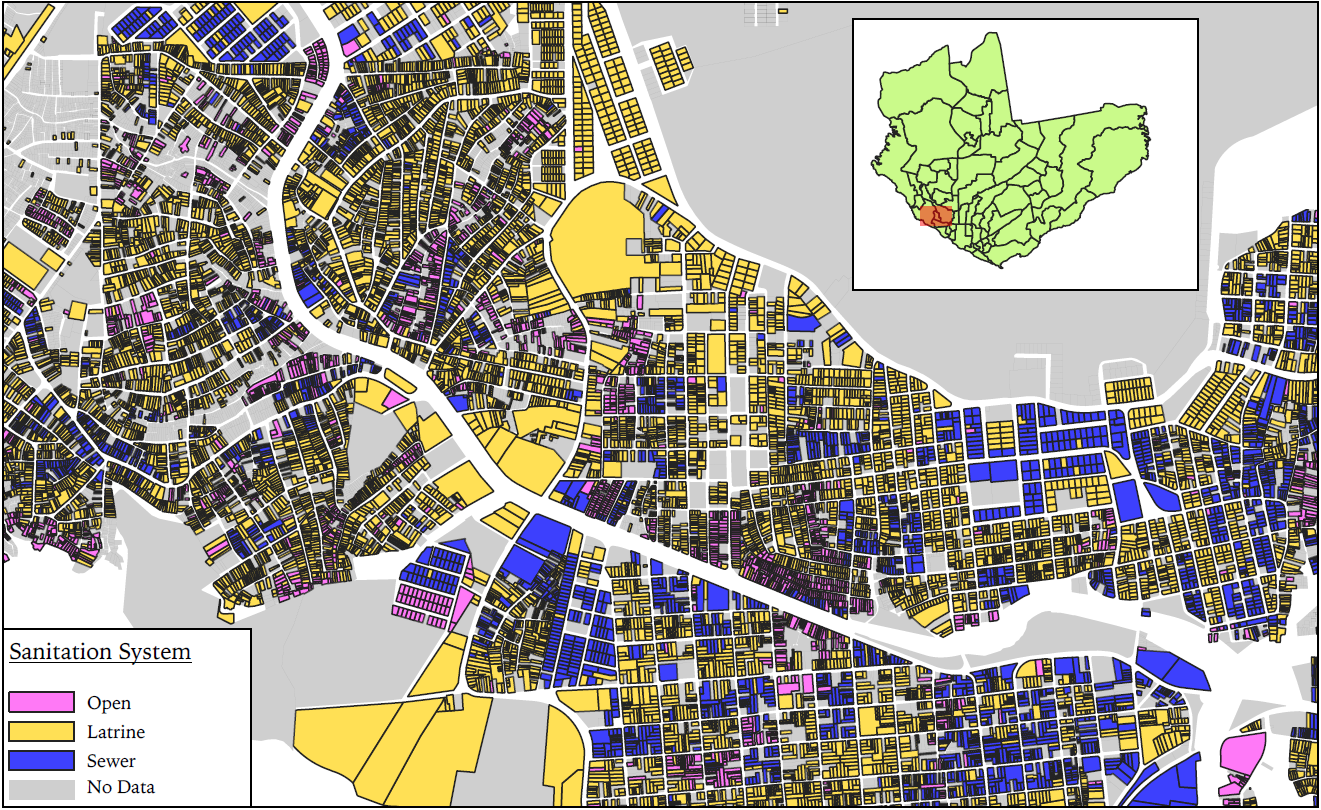

In recent research, we are able to address the role of the social contract in urban sanitation and tax compliance by focusing on the behaviour of residents in Manaus, Amazonas (Kresch et al. 2023). One of the largest cities in Brazil, Manaus is representative of the situation faced by many urban areas in developing countries with both low property tax compliance (less than 60% of households pay their tax bill) and non-universal access to improved sanitation (less than 25% of households have sewer connections). Crucially – and not unique to this setting – access to the sewer network varies across the city with very fine granularity, resulting in homes and business directly adjacent to each other routinely differing on whether they have a sewer connection (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Access to the sewer network across Manaus

Like many cities, Manaus employs a presumptive approach to calculating the property tax. This approach entails keeping an updated cadaster of easily observable characteristics for all properties in the city (e.g. number of stories, roofing material, lot size). As these characteristics are meant to be easily verified and updated by tax assessors on the street, the property tax formula does not factor in whether a building has sewer access (as opposed to a backyard latrine or no system). Thus, throughout the city there are households that have identical tax bills but have significantly different access to WASH services.

Do households with sewer access have higher tax compliance?

Exploiting variation in sewer access for over 200,000 households across the city, we find that households with a connection to the city sewer system were significantly more likely to pay their property taxes, compared to households with off-grid latrine systems and households that had no access to any form of improved sanitation.

For households with the same tax liability but different sanitation options, we find that those with sewer connections are 35% more likely to be pay their property taxes compared to households that lack any improved sanitation. Households with private backyard latrines also had a 22% increase in tax compliance compared to the non-WASH households, with the difference in compliance rates between sewer and latrine households being significant.

To further investigate whether the social contract is playing a role in the observed difference in compliance rates across sanitation type, we conducted a household survey to elicit views on the local government and the current tax system. We find that households with access to the city sewer network were significantly more likely to take the view that the quality of local government services is good. Moreover, this effect is entirely driven by compliant households; those households who had sewer access but were delinquent on their property tax payment did not hold significantly more favourable views of municipal services.

Conclusion

Taken together, our findings are consistent with a story in which the social contract plays a significant role in households deciding whether to pay their property taxes. Households with access to the sewer network are more likely to be in tax compliance and to have a more positive view on the local government’s ability to provide services.

Our findings are particularly relevant in the densely populated and rapidly urbanising areas across the global south, where tax compliance and access to improved sanitation are both low. Despite the large fixed costs inherent in constructing and maintaining urban sewer systems, our results suggest these costs could be partially offset by the newly generated tax revenue from increased property values and compliance rates. Such a financial sustainable system would move the world ever closer to achieving the goal of universalisation of WASH services.

References

Besley, T, and T Persson (2013), Taxation and development. In Handbook of public economics (Vol. 5, pp. 51-110).

Castro, L, and C Scartascini (2015), “Tax compliance and enforcement in the pampas evidence from a field experiment.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 116: 65-82.

Duflo, E, S Galiani, and M Mobarak (2012), “Improving access to urban services for the poor.” Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab Report.

Haq, O, A Q Khan, B Olken, and M Shaukat (2020), Rebuilding the social compact.

Kresch, E P, M Walker, M C Best, F Gerard, and J Naritomi (2023), “Sanitation and property tax compliance: Analyzing the social contract in Brazil.” Journal of Development Economics, 160: 102954

Okunogbe, O (2021), Becoming Legible to the State.

Troeger, C, B F Blacker, I A Khalil, P C Rao, S Cao, S R Zimsen... and R C Reiner (2018), “Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoea in 195 countries: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 18(11): 1211-1228.

Weigel, J L (2020), “The participation dividend of taxation: How citizens in Congo engage more with the state when it tries to tax them.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(4): 1849-1903.

World Bank (2022), All Drops in the Bucket for Universalization: Public Expenditure Review of Water and Sanitation in Brazil. World Bank.