Correcting inaccurate beliefs about peers can strengthen social networks, encourage people to talk about their financial and mental health concerns, and improve socioeconomic outcomes in settings where individuals lack support from formal institutions

People rely on their social networks to smooth consumption, gather information, and seek advice, especially when they lack access to formal support (Breza et al. 2019). However, networks can only function as social safety nets if individuals demand support in the first place. A key reason why they might not do so is if they are concerned about violating social norms. For example, people may not reach out to others to ask for financial support if they believe that it can hurt their reputation and reduce access to economic opportunities. Such concerns can adversely affect the network’s ability to act as a safety net. While it is difficult to change norms, we know from existing research that it can be possible to change people’s inaccurate beliefs about them (Bursztyn and Yang 2022, Haaland et al. 2020, Bursztyn et al. 2020).

In our research (Jain and Khandelwal 2024), we study whether inaccurate beliefs about others’ willingness to engage with financial and mental health concerns can generate ‘silent networks’ i.e. networks with limited useful interactions despite high benefits. We present experimental evidence to show how belief correction can increase useful social interactions. Then, we account for how misperceptions can naturally arise in social networks (Jackson and Yariv 2007, Jackson 2019), allowing us to predict whether our intervention would shift the existing equilibrium, and run policy counterfactuals

People do not engage in useful social interactions

We work with a sample of low-income informal sector workers, who are primarily employed in waste picking, and their families living in slum-like conditions in Delhi, India. We find that majority of individuals in this setting have volatile incomes, high levels of stress, and do not have access to formal sources of assistance. For instance, half of them do not have access to bank accounts, and accessing professional support for mental well-being is also not an option. As a result, social networks must act as social safety nets and help individuals deal with shocks. However, 75% report facing consumption crisis events in the last six months and 50% report feeling that the difficulties they face seem like they cannot be overcome. The majority do not interact with their peers about financial and mental well-being even though we find that these interactions can help and there is no alternative social network (e.g. in rural areas) that they rely upon.

Could this be due to pessimistic beliefs about social norms? We asked individuals for their beliefs about how many community members out of any randomly chosen 10 would be willing to engage around mental and financial concerns, as well as their own willingness to engage. We find that 68% (58%) underestimate the willingness of others to engage around mental health-related (financial well-being related) concerns.

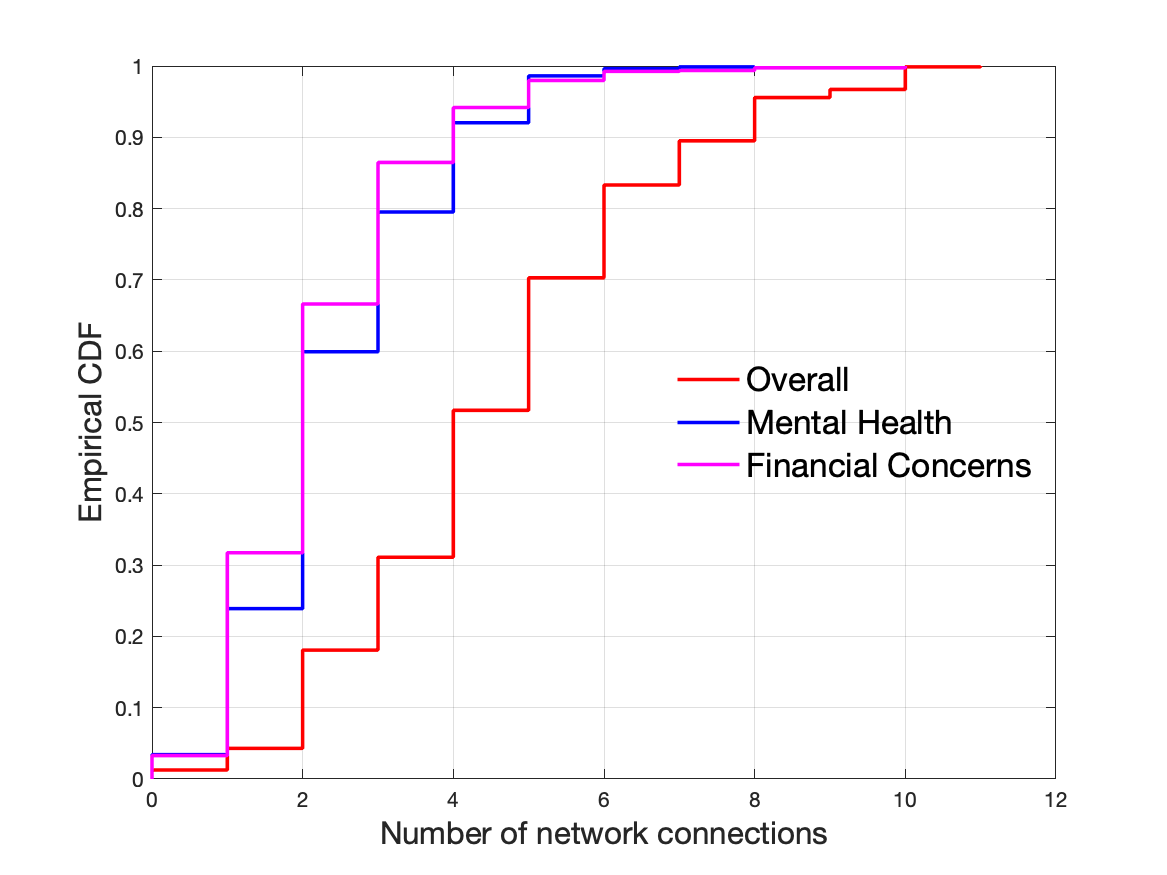

Figure 1 visualises the number of connections that individuals have in their mental health advice-taking network (i.e. to discuss mental health concerns), financial concerns network (i.e. to discuss monetary/employment concerns), and the overall social network (i.e. any interaction). We find that the gaps between these networks are correlated with beliefs; those who are more pessimistic about others’ willingness to engage have fewer connections in their advice-taking networks relative to their total connections in the overall social network.

Figure 1: Number of network connections in the mental health advice-taking network (i.e. to discuss mental health concerns), financial concerns network (i.e. to discuss monetary/employment concerns), and overall social network (i.e. any interaction)

Can an information provision intervention help?

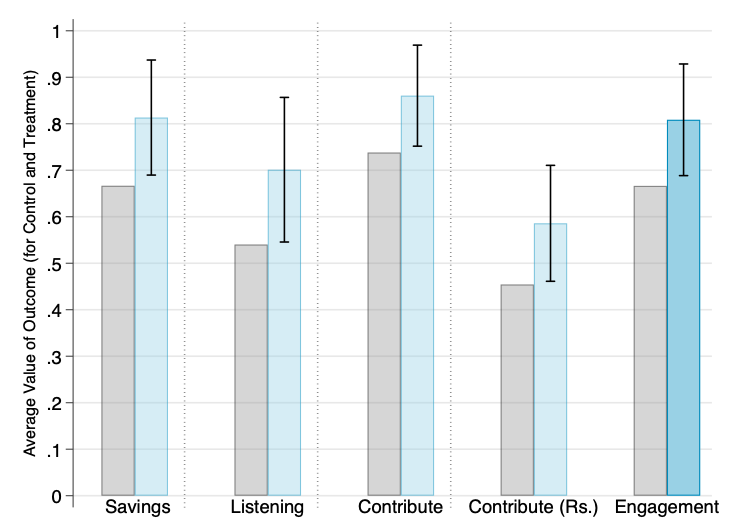

We implement a randomised controlled trial where we provide average sample-level information about others’ willingness to engage with concerns about mental and financial well-being. We detect a 15-percentage point increase in the willingness to participate in savings groups and a 16-percentage point increase in participation in a listening service where they would train to listen to the concerns of others in their community. Moreover, treated participants pay significantly larger financial contributions to set up the listening service (Figure 2). These contributions are as large as 13% of daily income.

Figure 2: The impact of providing information

Notes: The above figure shows the average value of each outcome for the control group (in grey) and the treatment group (in blue) with 95% confidence intervals for the difference between the two values. “Savings”, “Listening”, and “Contribute” refer to binary variables indicating whether the individual is willing to participate in savings groups, train and volunteer for a listening service, and contribute to setting it up. Engagement is an average of these three variables. “Contribute (Rs.)” is the monetary contribution made by the individuals, normalized to be between 0 and 1.

Furthermore, two years later, we find that those who report being exposed to this information (either having been a participant in the intervention and/or having heard the treatment information from others) have significantly more optimistic beliefs, higher dialogue intensity around these topics, and lower self-reported consumption volatility.

Why does the intervention work?

We first show that experimenter demand effects do not drive our results. Instead, we find that the intervention works because it reduces people’s perceived costs of violating the social norm.

Existing research shows that signaling and shame can prevent people from seeking advice (Chandrasekhar et al. 2018). To identify the role played by such concerns in reducing conversations around mental and financial well-being in our setting, we ask individuals to predict whether a randomly chosen person B would approach a random person A to seek support for mental and financial concerns. Importantly, we vary A’s characteristics in terms of how connected they are in the network (to get at reputational costs arising due to gossip), their attendance in a sensitivity training session (to get at interaction costs due to fears about being met with insensitivity), and their contacts in private jobs (to get at signaling costs due to concerns about not receiving information about job opportunities).

We find that individuals think that person B would not seek support from person A in ~23% of the cases. While all three costs matter in our setting, interaction, and reputational costs significantly affect the predictions of those who are themselves pessimistic about others’ willingness to engage. This shows that these costs matter precisely for the subgroup most likely to benefit from a belief correction intervention.

Have we changed equilibrium beliefs and engagement? What would it take to change it?

To answer this, we adapt and structurally estimate a model (Jackson and Yariv 2007, Jackson 2019) leveraging the random variation induced by the RCT. We use this to comment on why individuals may have inaccurate beliefs in the first place, predict whether our intervention would lead to persistent change in equilibrium beliefs, and analyse how the effect of our intervention compares to interventions that do not target beliefs. These include interventions that increase the perceived benefits of interactions (e.g. conditional cash transfers) or reduce the cost of violating norms without targeting beliefs (e.g. a job referral service). Under the model and estimation assumptions, we find that networks are indeed stuck in a trap of low dialogue. Furthermore, despite the positive short-run and two-year effects of our intervention, we predict that belief correction will not lead to a permanent change in equilibrium in our setting.

Moreover, we find that very costly interventions (such as those that shift the perceived benefits of interacting by 50% of their current mean) are needed to generate a permanent effect at least as large as the short-run effect of our RCT. However, the silver lining is that belief correction can be used as a means to generate the demand and funding for such costly interventions.

References

Breza, E, A Chandrasekhar, B Golub, and A Parvathaneni (2019), "Networks in economic development", Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 35(4): 678-721.

Bursztyn, L, A L González, and D Yanagizawa-Drott (2020), "Misperceived social norms: Women working outside the home in Saudi Arabia", American Economic Review, 110(10): 2997-3029.

Bursztyn, L and D Y Yang (2022), "Misperceptions about others", Annual Review of Economics, 14: 425-452.

Chandrasekhar, A G, B Golub, and H Yang (2018), "Signaling, shame, and silence in social learning", National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 25169.

Haaland, I, C Roth, and J Wohlfart (2023), "Designing information provision experiments", Journal of Economic Literature, 61(1): 3-40.

Jackson, M O (2019), "The friendship paradox and systematic biases in perceptions and social norms", Journal of Political Economy, 127(2): 777-818.

Jackson, M O and L Yariv (2007), "Diffusion of behavior and equilibrium properties in network games", American Economic Review, 97(2): 92-98.