Encouraging tuberculosis patients in India to refer others showing symptoms for testing led to a significant uptick in testing and the identification of new cases

Tackling tuberculosis: The power of peer referrals in India

Tuberculosis (TB) is a contagious disease that usually attacks the lungs but can also spread to other parts of the body, like the brain and spine. It is caused by a type of bacteria called Mycobacterium tuberculosis - this bacterium is thought to be over 3 million years old. Knowledge of the disease dates back to ancient Greece and Rome, and it was the top cause of death in the US at the beginning of the 20th century. In 2021, 10.6 million people fell ill with TB (WHO 2022). The disease is most common among vulnerable populations in poor countries in Africa and Asia. Mortality from untreated TB is high, and the disease is highly debilitating even among those who survive it, with serious, often devastating consequences for human productivity and well-being. But TB is treatable. Effective antibiotic treatments for TB became widely available in the mid-20th century, leading to a significant decline in TB deaths globally. The World Health Organization estimates that TB treatment saved 74 million lives between 2000 and 2021 (WHO 2022). However, with more than 1.6 million deaths annually, TB remains the most deadly infectious disease globally – a position from which it was only briefly displaced at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic (WHO 2022).

The key reason why TB is still so harmful is not that we lack treatment, it is that many of those with the disease go undetected and undiagnosed, and many detected cases do not get treatment. Also, many who start treatment do not complete it. Not completing treatment contributes to drug-resistant or multi-drug-resistant TB, i.e. TB that does not respond to at least isoniazid and rifampicin, the two most powerful anti-TB drugs (Gandhi et al. 2010).

Defeating TB requires efforts on many fronts

TB is a significant public health concern in India, a country that harbours a quarter of the world's TB cases, with an estimated 2.1 million cases detected in 2021 alone. India's public health system, though robust in certain aspects, struggles with the sheer volume of latent and active TB cases. Resource constraints and the overwhelming burden on public health facilities mean intensive contact tracing and individual-focused attention are often unfeasible. The healthcare system's limitations inadvertently contribute to the persistence of TB, and its highly infectious nature makes undiagnosed patients unintentional conduits for the disease's spread. Families, communities, and healthcare workers are continually at risk, amplifying the health, social, and economic repercussions of this endemic problem. Furthermore, the stigma attached to a TB diagnosis exacerbates the issue, because it can make individuals reluctant to seek testing and treatment and lead to a vicious cycle of underdetection and continued transmission. Together, these challenges necessitate alternative strategies to bridge the gaps in TB detection and treatment.

Tackling underdetection in India

In our recent research, Goldberg, Macis and Chintagunta (2023), we tackled the issue of underdetection in India, where about 40% of TB cases are never reported to the public health authorities (Cowling et al. 2014). Amid the myriad challenges to detection, using private information could complement other efforts. Current TB patients, with their personal experience and knowledge about the disease and its treatment, could help in reaching out to others. Their information and understanding offer a way for potential patients to seek help that is relatable and likely to be trusted more than information conveyed by a health worker.

Recognising this potential, we conducted a field experiment to explore the effectiveness of peer referrals in TB detection and treatment. Established TB patients were encouraged and financially incentivised to refer others showing symptoms of TB for testing. Individuals under appropriate medical care possess firsthand knowledge about various aspects of TB, including screening, testing, and treatment. Their personal experience as patients and their likely connections to others at risk - due to shared risk factors and the contagious nature of TB - position them uniquely to aid in the identification of and timely communication with those who would benefit from testing and treatment. Existing patients may also offer credible endorsements for healthcare providers and the advantages of proper treatment, delivering personal testimonials that might be more persuasive to potential patients than information from health workers. Thus, peer referrals offer an outreach strategy that can enhance identification and persuasion of at-risk individuals alongside the work of public health workers.

We collaborated with Operation ASHA, an NGO that operates Directly Observed Treatment Short Course (DOTS) centers across several cities, aligning with the Indian government's TB control programme, the Revised National Tuberculosis Programme (RNTCP). In our study, 122 DOTS centers treating 3,176 patients across nine cities were randomly divided into either a control group, which followed standard patient intake procedures, or into groups employing one of nine active case-finding strategies. These experimental strategies included different conditions and types of incentives for referrals and varied whether prospective patients were approached directly by current TB patients from their social networks or by health workers following up on leads provided by those existing TB patients.

Did peer referrals work?

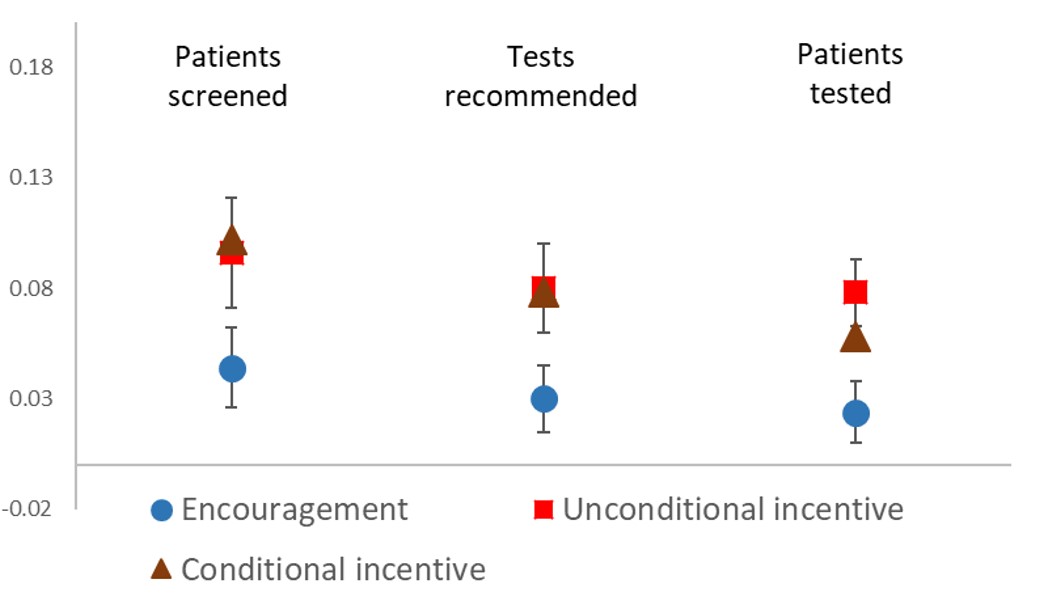

Leveraging the power of community and personal relationships led to a significant uptick in testing and the identification of new TB cases. In particular, the results showed a notable impact of financial incentives, which doubled the number of prospective patients seeking screening for TB. On average, incentivising existing patients led to one new patient being screened for every ten existing patients, a marked increase from one in 22 without incentives. The screening proved to be well targeted – incentives also significantly increased the number of people who were determined to have symptoms of TB and were sent for sputum testing at government centers. Ultimately, patients tested as a result of peer referrals were more likely to have TB than the average person tested over the same time period, demonstrating the effectiveness of peers in targeted outreach.

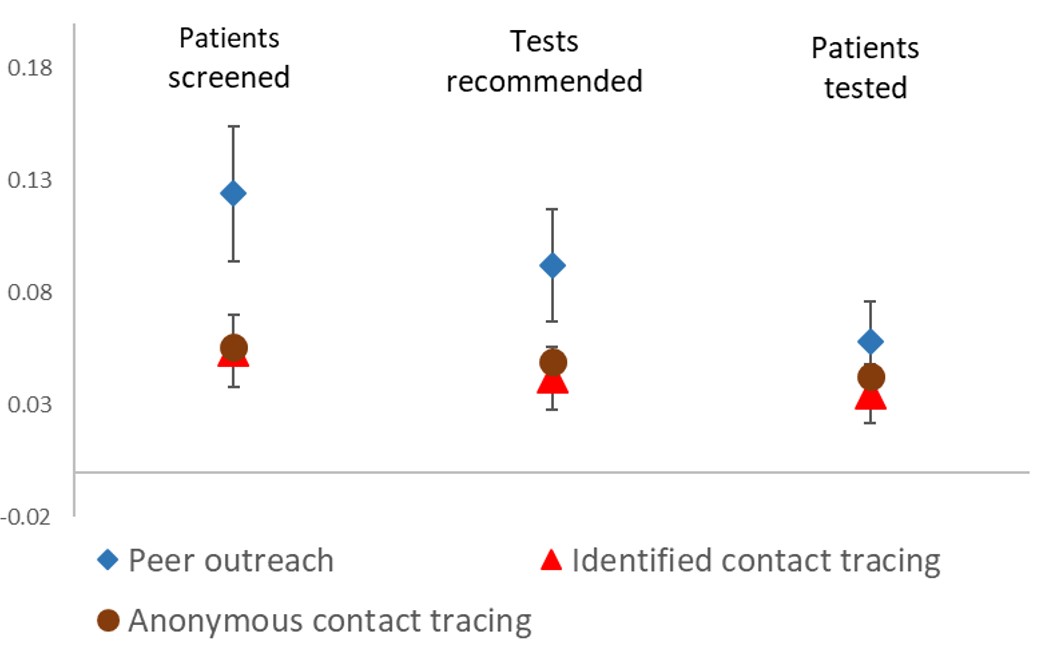

Direct outreach by existing TB patients was found to be more effective than outreach by health workers, and when combining incentives with peer outreach, we observed even more pronounced results. Incentivised peer outreach led to one new patient being screened for every 5.6 existing patients and one new symptomatic individual sent for testing for every 7.4 existing patients. Incentivised peer outreach also had statistically significant effects on the number of patients with active TB who were identified, and nearly all of these patients initiated treatment immediately.

Figure 1: Effects of incentives on TB screening and testing (Source: Goldberg et al. (2023), Table 2.)

Figure 2: Effects of outreach strategies on screening and testing (Source: Goldberg et al. (2023), Table 3.)

Peer referrals were cost-effective, making them a good additional strategy for detecting TB cases. Peer outreach with financial incentives led to the identification of active TB cases at a cost of $114 per case, a stark contrast to the $300-$400 incurred through traditional health worker outreach. This cost-effectiveness is essential in ensuring the sustainability and scalability of peer referral initiatives.

The success of the peer referral initiative highlights the critical role of community involvement and peer support in healthcare. Harnessing the power of personal networks, insights, and experiences paves the way for a more inclusive and effective approach to TB management, providing hope and a practical path forward in the ongoing fight against this persistent health menace.

This experiment’s implications resonate beyond TB. Similar challenges plague the detection and treatment of other diseases, such as HIV/AIDS and STDs. The insights from our study offer a blueprint for harnessing community networks and peer outreach in enhancing detection and treatment rates across various health concerns. However, the efficacy of peer-based outreach is likely context-specific.

Linking past lessons to new challenges: The case of Zambia’s COVID-19 outreach

A recent study by Burlando et al. (2022) titled "Passing the Message: Peer Outreach about COVID-19 Precautions in Zambia" applied an approach similar to that from the TB study in India, focusing on the dissemination of health information during a public health emergency.

Both studies share foundational principles:

- The attempt to curtail the spread of a communicable disease.

- The significance of observable health behaviors among peers.

- The challenge of overcoming public misinformation and misunderstanding of the disease.

However, there were important differences between the two cases. Both the risk of infection and knowledge of treatment were more personal for TB in India than for COVID-19 in Zambia. As a consequence, targeted outreach was less feasible, and messages were generic rather than rooted in personal experience, in the COVID-19 application.

A notable finding from the Zambia study was that individuals willingly forwarded public health messages about COVID-19 when encouraged to do so. This mirrors the findings from the TB study in India and underscores the potential of peer-based messaging in public health contexts. However, unlike in India, financial incentives did not increase the sharing of information in Zambia, and dissemination of information did not lead to a corresponding observable change in COVID-19 precautionary behaviors among the recipients of these messages.

Several factors may contribute to the limited effect of the peer-driven outreach efforts in Zambia. By the time the study was conducted, COVID-19 information was already being widely disseminated through various mediums like radio, newspapers, and social media. The people asked to share messages in Zambia were randomly selected from a sample of cell phone users, and had no specific personal experience with or knowledge of COVID-19 testing or treatment. Consequently, the intervention's messages may not have provided new or especially credible information to the recipients. Also, the intervention in India targeted people who had symptoms of TB, and recommended that they take steps to remediate their health, while in Zambia, the advice was to take precautionary measures. Prior research indicates a greater willingness to invest in curative than preventative health care (Dupas 2011).

Moreover, the null results of the Zambia study align with other global attempts to influence COVID-19 precautions via similar mediums. There seems to be a consistent challenge in converting information dissemination into tangible behavioral change, especially when the information is not novel or personalised.

In summary, while the TB study in India and the COVID-19 study in Zambia share similar methodologies and foundational principles, the outcomes and the contextual challenges highlight the complexities of public health outreach. As the world continues to grapple with health crises, understanding these nuances will be instrumental in crafting effective strategies for information dissemination and behavioral change.

References

Burlando, A, P Chintagunta, J Goldberg, M Graboyes, P Hangoma, D Karlan, M Macis and S Prina (2022), “Passing the Message: Peer Outreach about COVID-19 Precautions in Zambia” National Bureau of Economic Research (No. w30414).

Cowling, K, R Dandona, and L Dandona (2014), “Improving the estimation of the tuberculosis burden in India.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 92: 817-825.

Dupas, P (2011), “Health behavior in developing countries.” Annu. Rev. Econ. 3(1): 425-449.

Gandhi, N R, P Nunn, K Dheda, H S Schaaf, M Zignol, D Van Soolingen, ... and J Bayona (2010), “Multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: a threat to global control of tuberculosis.” The Lancet, 375(9728): 1830-1843.

Goldberg, J, M Macis, and P Chintagunta (2023), “Incentivized Peer Referrals for Tuberculosis Screening: Evidence from India.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 15(1): 259-291.

WHO (2022), “WHO Global Tuberculosis Report 2022.” https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2022