Income differences between high- and low-income countries reflect differences in technology adoption and skill endowments. Ensuring the right worker finds the right job - improving worker-job matching – can play an important role in realising the gains of technology and endowment upgrading.

Read "Meritocracy across Countries" by Oriana Bandiera, Ananya Kotia, Ilse Lindenlaub, Christian Moser & Andrea Prat.

A meritocratic labour market is one where workers are allocated to jobs based on their skills or productivity, rather than on other attributes such as their social status, their network or their wealth. In this episode of VoxDevTalks, Oriana Bandiera and Ilse Lindenlaub discuss the findings from their latest research (co-authored with Ananya Kotia, Christian Moser and Andrea Prat). They discuss whether high-income countries have more meritocratic labour markets and the importance of meritocracy for economic development.

What mechanisms underlie the relationship between worker-job matching and economic development?

In a perfectly meritocratic labour market, worker-job matches are such that output is maximised, implying that jobs go to those with the most suitable skills. One potential barrier that may explain why some countries have less meritocratic labour markets are ‘matching frictions’ – factors that make it difficult for the right job seeker to find the right job and vice versa. Some countries may face higher frictions that prevent jobs being allocated on skills alone. Often these frictions are a result of the institutional structure of an economy. Informal institutions, such as the degree of tolerance for nepotism or corruption, and formal institutions, such as a lack of enforcement of discrimination laws, can inhibit worker-job matching based on skill.

Differences in technology adoption and skill endowments are important for explaining cross-country income differences, but may also weaken incentives for skill-based matching. Advanced technologies often require skilled workers and thus motivate the matching between high skill supply and demand. Similarly, differences in skill levels and endowments in countries may affect the meritocracy of labour markets.

How can we capture differences in meritocracy and skill-based matching across countries?

To try and capture the variation in meritocracy across countries, the authors use an OECD dataset of 28 countries that collects data from a quantitative test measuring the skills of adults and provides information on numerical and literacy competencies. They add that this data has the advantage of not being self-reported and allows them to avoid using years of education as a metric. Because the positive correlation between skills and years of education is far stronger for high-income countries than low-income countries, using years of education as a proxy of skills between countries is heavily flawed.

‘Ten years of education in UK is not the same as in Finland or Ecuador. Our measure is an objective test-based measure which therefore does not have to rely on the education system being the same.’

There is more skill-based sorting in high-income countries

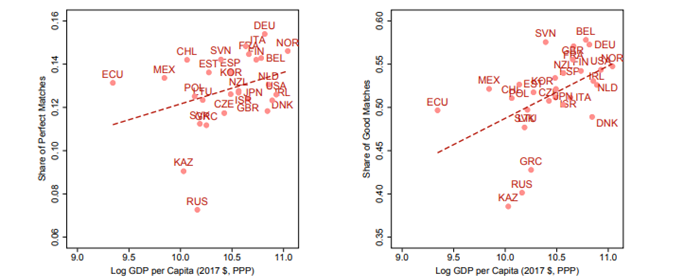

Figure 1: Intensive margin: more perfect and good worker-job matches in high-income countries

Note: The left panel shows the share of ‘perfect’ worker-job matches, defined as matches in which the worker’s skill quintiles equal their job’s skill requirement quintiles in each of the two skill dimensions. The right panel shows the share of ‘good’ worker-job matches, defined as matches in which the worker’s skill quintiles are no more than one quintile away from, their job’s skill requirement quintiles in each of the two skill dimensions. Source: PIAAC. Figure 2 in Bandiera et al. (2024).

As can be seen in Figure 1, there is more skill-based sorting among high-income countries (e.g. Norway or Ireland) along the intensive margin (workers’ skills are more aligned with their job skill requirements). The same relationship exists along the extensive margin such that employed workers are more positively selected on skills.

How important is meritocracy at explaining cross-country income differences?

Using a ‘decomposition exercise’ based on the economic model they develop; the authors attempt to capture how much of the difference in aggregate output between countries can be explained by low meritocracy in the labour market. They conclude that higher matching frictions and lower levels of meritocracy in poorer countries are not the main culprit behind these countries' lower incomes. Instead, income differences reflect lower technology adoption and lack of a good fit between skilled supply and skilled demand. Both low levels of technology adoption and endowment constraints curtail the incentive to sort on the labour market leading to a less meritocratic labour market. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of the gains from moving onto the technological and skill endowment frontier can be realised through improved sorting.

‘We suggest that the lack of meritocracy is not the source of the lower income in these poor countries, but rather is a consequence of not adopting the right or most advanced technology and lacking the appropriate endowments.’

They use a counterfactual to find out how much output is lost because of low levels of labour market meritocracy, given the positive relationship between labour market meritocracy and income levels. All countries would see increases in aggregate output however the gain is far larger for low-income countries.

Nevertheless, the gains that could be made from assigning poor countries the same frontier technology and highly skilled workforce and jobs demanding those skills as Norway, would lead to gains of a magnitude larger than those that could be achieved through removing matching frictions.

What are the policy implications?

Although reducing matching frictions can help improve the allocation of jobs, helping improve the skills of workers in an economy (i.e. the endowments) and spurring the adoption of new technologies can have far greater impacts on closing the income gap between low- and high-income countries. Therefore, to secure the best return for every pound, policy should focus on investing in upskilling workers through education (e.g. Andrabi 2024) or improving technology adoption (e.g. Aker and Jack 2022).

‘All the fights against corruption, nepotism…which can improve the allocation of jobs in low-income countries can only give us a multiple of the GDP of that country…but given the huge differences between high- and low-income countries it does not do much to close much of the gap.’

True meritocracy at the global level: Eliminating country borders

As a final counterfactual the researchers examine how global output would change if they eliminated all country borders such that any worker from any country can take any job anywhere. This would lead to a worldwide output gain of 11% due to the improved matching between workers and jobs. High skilled workers from lower income countries (e.g. Mexico or Ecuador) could be employed in high skilled jobs elsewhere so that their skills were fully utilised.

References

Bandiera, O, Kotia, A, Lindenlaub, I, Moser, C, and Prat, A (2024), "Meritocracy across Countries," NBER Working Paper No. 32375.