The apparent positive impact of training coffee farmers in Rwanda was driven by negative spillover effects on farmers who did not receive training

Agriculture is of utmost importance to low-income economies, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where agricultural productivity is increasingly lagging behind the rest of the world (FAOSTAT 2022). To try and address this issue, governments and NGOs conduct agricultural training programmes to promote the adoption of yield-enhancing technologies. These programmes often rely on a few trained farmers within each community disseminating best practices through social networks. However, existing experimental studies on the diffusion of agricultural innovation through social networks have yielded mixed results (Suri and Udry 2022). This literature also does not address the possibility of negative spillovers imposed on untrained farmers. One such externality could occur if an intervention increases the demand for scarce inputs in settings where input markets are frequently far from perfect. Another source of potential externalities from an intervention that affects some people but not others is the re-wiring of social networks (Banerjee et al. 2021): if trained farmers find it advantageous to only socialise with other trained farmers, this could affect the sharing of both information and risk in the community, potentially penalising farmers who do not receive training. Conversely, if control farmers seek out treatment farmers, this could accelerate the transmission of any intervention (Comola and Prina 2021).

Context

Our study investigates these previously under-researched questions using a two-stage randomised evaluation of a coffee agronomy training programme in Rwanda (Duflo, Keniston, Suri & Zipfel 2023). The programme, implemented by a leading agribusiness NGO, focused on providing agronomy training to farmers to improve their yields. The selected farmers received monthly instruction modules and refresher modules over two years, covering various agronomic practices related to coffee production.

Capturing impacts of coffee agronomy training

To measure direct and indirect impacts, we implemented a two-level evaluation design, similar to Crépon et al. (2013). First, we collected applications for the training programme from coffee farmers. Second, we randomly varied treatment concentration at the village level across 27 villages: in approximately one third of villages, 25% of farmers who signed up were to be enrolled in the training, in another third, 50%, and in the final third, 75%. Finally, the 1,594 farmers who applied for the training were allocated to treatment and control following the assigned proportions in each village.

Figure 1: Visible effects of best agronomic practices around coffee tree nutrition

We collected ten rounds (including four post-treatment) of data on a wide range of indicators to measure the impacts of the training on farmers’ knowledge and adoption of the practices as well as on their yields. However, we were concerned that farmers might erroneously report adoption simply because they were asked about it repeatedly — a concern that proved valid. Therefore, in addition to survey data, our enumerators also audited the coffee plots through direct observation. Figure 1 illustrates that the extent to which a tree is well nourished, for instance, can be assessed through plot audits: a stark contrast is evident between the coffee trees; one, poorly nourished, exhibits yellow and curled leaves, while the other boasts vibrant and healthy green leaves. Finally, to measure both diffusion effects and any impact on social connections, we collected social network data before and after the training, constructing complete social network maps of all 3,000 coffee-growing households in the sub-district. We also collected GPS coordinates of plots and households to construct two measures of neighbours: people farmers live close to and people whose coffee plots are close to each other.

Results

The results showed significant effects on knowledge and self-reported adoption of the agronomic practices. Similarly, within-village comparisons of treatment and control farmers suggest that treatment farmers used more inputs than control farmers, and their yields were approximately 6.7% higher. However, tree audits show no treatment effects on adoption of the practices taught in the trainings.

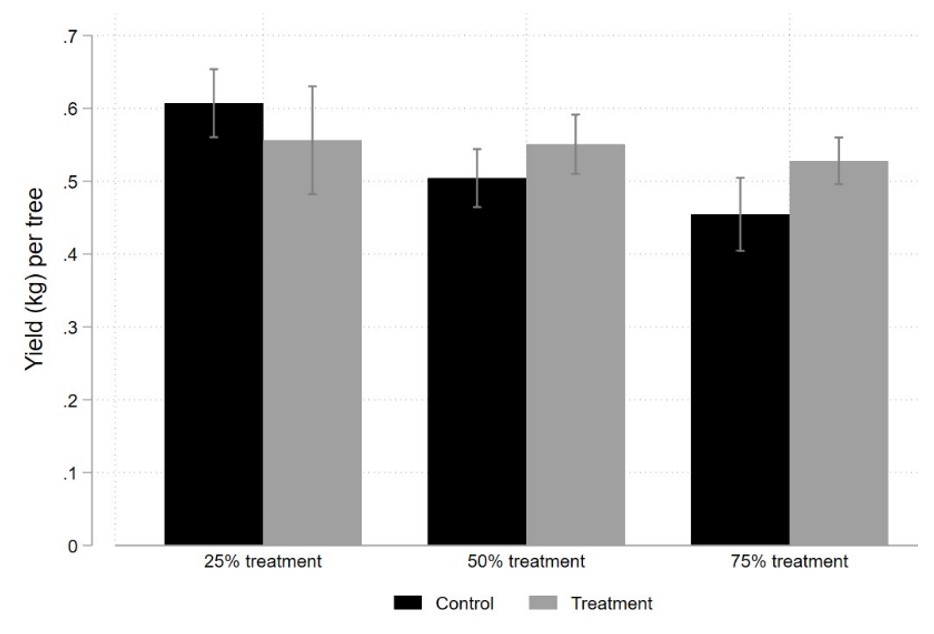

Figure 2: Treatment-Control comparison of mean coffee yields, by village treatment share

Do spillovers undermine the training programme?

An analysis exploiting the exogenous variation in village-level shares of treated farmers helps explain this apparent contradiction. As Figure 2 illustrates, we find clear evidence of negative spillovers: the higher the fraction of treated farmers in a village, the lower the yields of the control group. Control farmers in heavily treated villages also used less chemical fertiliser (NPK) and labour days per tree, and their trees had visibly poorer leaf health. Thus, the apparent positive impact of the programme on yields is largely an artifact of the fact that yields went down for control farmers. Not surprisingly, we find no evidence of knowledge diffusion in the social network or to geographic neighbours.

We conclude that these negative externalities likely stem from the crowding out of inputs in limited supply. Indeed, the agronomy training programme took place in a context where NPK was not widely available in Rwanda. The government phased out the direct delivery of fertiliser during our study period, relying on private actors, cooperatives and agro-dealers to take over, but this happened slowly and imperfectly. We also know from prior research that agricultural labour markets are often far from perfect (Breza et al. 2021).

The fact that the treatment does not increase the yields of treated farmers but may have decreased those of control farmers suggests that training some farmers but not others may decrease aggregate output by increasing input misallocation. Estimates of a simple coffee production function suggest that they are no different across treatment and control farmers, meaning that input reallocation is unlikely to have affected efficiency in overall coffee production in this sample.

Finally, we examine another source of potential spillovers from the intervention affecting some farmers but not others: the fact that the treatment may itself have modified the structure of social networks. Treated farmers formed new connections within the treatment group, primarily among people with whom they attended the training. However, these new connections did not come at the cost of friendships in the control group. In fact, treated farmers appeared to have more overall connections. Conversely, we did not find any evidence that the control group sought out trained farmers to gain access to their increased knowledge about coffee agronomy. The social effect of the training seems to have been largely limited to the relationships formed during the actual training meetings themselves.

Key takeaways

In sum, this study underscores the risks associated with assisting some farmers while neglecting others in imperfect market conditions. Furthermore, the fact that the naive comparison between treated and control farmers within a village would have led to a serious overestimate of the benefits of the programme without a village-level randomisation calls for caution in the evaluation of agricultural extension programmes.

References

Banerjee, A V, A G Chandrasekhar, E Duflo, and M O Jackson (2021), “Changes in Social Network Structure in Response to Exposure to Formal Credit Markets.” NBER Working Paper No. 28365.

Breza, E, S Kaur, and Y Shamdasani (2021), “Labor rationing.” American Economic Review, 111(10): 3184–3224.

Comola, M and S Prina (2021), “Treatment Effect Accounting for Network Changes.” Review of Economics and Statistics, 103(3): 597–604.

Crépon, B, E Duflo, M Gurgand, R Rathelot, and P Zamora (2013), “Do Labor Market Policies have Displacement Effects? Evidence from a Clustered Randomized Experiment.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(2):531–580.

Duflo, E, D Keniston, T Suri, and C Zipfel (2023), “Chat Over Coffee? Diffusion of Agronomic Practices and Market Spillovers in Rwanda.” NBER Working Paper 31368

FAOSTAT (2022), “Technical report, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT Statistical Database.” [Rome]. Accessed September 22, 2022.

Suri, T and C Udry (2022) “Agricultural Technology in Africa”, VoxDevLit, 5.1