Evidence from land reform in El Salvador shows that private property rights are not necessarily more efficient than cooperative property rights

"On March 5th, we went to sleep as poor colonos [labourers]. On March 6th, we woke up rich, as landholders."

Cooperative Member, La Maroma Cooperative, 2017

Editor's note: This article has been amended to reflect the findings of a replication of the underlying paper. Results on worker incomes and inequality have therefore been removed.

Latin America has high levels of land inequality. In fact, it is frequently cited as a key driver of Latin America’s comparative underdevelopment (Engerman and Solokoff 2002). In response to these high levels of inequality, over half of Latin American countries have attempted land reform programmes to transform haciendas, in which an owner contracts labourers to work on the land, into agricultural cooperatives, in which workers jointly own and manage production. Figure 1 below illustrates the Latin American countries that have attempted a land reform since the 1920s.

Figure 1

Despite the widespread prevalence of land reforms to create cooperative property rights systems, there is no causal evidence on the effects of such rights on agricultural productivity or development (see Pencavel 2013) for a review). The main empirical challenge when studying the impacts of cooperative property rights relative to outside ownership is that property rights arrangements are not randomly assigned. Generally, the choice of property right system reflects the underlying characteristics of the land or the landowners, such as geography, capital requirements, or cultural practices. These characteristics may also affect outcomes such as productivity. This means that one cannot compare cooperatives to non-cooperatives to identify the impacts of cooperative property rights. This empirical challenge has left a gap in the research on the implications of cooperative ownership relative to outside ownership

El Salvador’s land reform

In my job market paper (Montero 2018), I use a unique feature of a land reform programme from El Salvador in 1980 to provide the causal impacts of cooperative property rights on agricultural productivity, crop choices, and economic development. Prior to the land reform, almost all of El Salvador’s agricultural production was organised in the form of haciendas. In fact, an estimated 1% of landholders owned over half of El Salvador’s agricultural land. As a result of the land reform, properties belonging to individuals with cumulative landholdings over 500 hectares were reorganised into cooperatives to be owned and managed by the former hacienda workers. However, properties belonging to individuals with cumulative land holdings under 500 hectares remained as privately owned haciendas.

El Salvador’s land reform had two important features that provide discontinuous variation in the probability of cooperative formation that I use to identify the impacts of cooperative property rights on economic outcomes:

- The cumulative ownership threshold of 500 hectares creates a set of similar properties, some of which happen to be owned by someone with more than 500 hectares in total holdings and were therefore reorganised into cooperatives, and some of which were owned by someone with cumulative holdings just below the threshold and therefore were not reorganised into cooperatives.

- The military executed the reform swiftly and took multiple steps to ensure its secrecy prior to its implementation. This prevented large landholders from being able to selectively adjust their cumulative landholdings to avoid expropriation prior to the implementation of the reform.

Cooperative property rights, agricultural productivity, and income

I use the 500 hectares threshold rule from El Salvador’s land reform law and a regression discontinuity design comparing properties that were reorganised into cooperatives to similar properties that were not reorganised to estimate the economic impacts of cooperative property rights relative to the private ownership system haciendas.

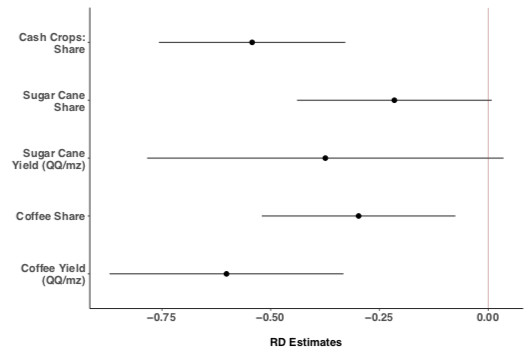

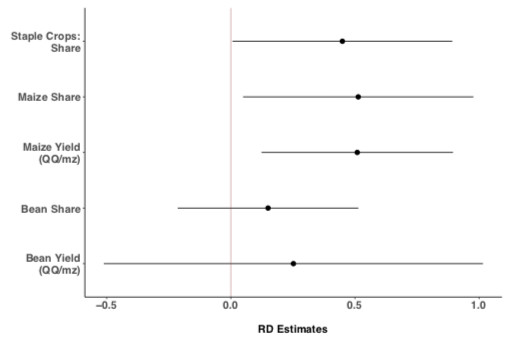

Using data from El Salvador’s 2007 census of agriculture, I find several key results related to agricultural productivity. First, relative to haciendas, cooperatives devote less land to cash crops, such as sugar cane and coffee, and are less productive at cash crops. However, this is not the case for staple crops, such as maize and beans. Cooperatives devote more land to produce staple crops and are actually more productive at these crops relative to haciendas. These results are presented in Figure 2. Interestingly, I find no evidence that cooperatives are on aggregate less productive than haciendas. By this I mean that cooperatives and haciendas have similar levels of revenues and profits per hectare.

Figure 2 Agricultural choices and productivity

Notes: Figure plots standardised (beta) regression discontinuity coefficients. Re- gressions use local linear polynomials and the MSE optimal bandwidth from Calonico et al. (2017). QQ represents quintals, where 1 quintal is equal to 100 kg. mz represents Manzanas, where 1 mz equals 1.72 acres.

These results are consistent with a property rights model of agricultural cooperatives, in which cooperative voters choose to redistribute cash crop earnings, which therefore reduces the cooperative’s productivity in the production of cash crops. In the model and in focus group discussions with cooperative members, because workers can consume staple crops directly if their output is taxed, staple crops are not subject to this redistribution. As a result, cooperatives are more likely to focus on staple crop production and are more efficient than haciendas at producing staple crops.

Policy implications: Cooperatives as a means for development

Despite the strong priors economists may have that private property rights are evidently more efficient than cooperative property rights, this is not necessarily the case - there are no differences in aggregate productivity between cooperatives and haciendas.

The findings speak to a modern policy question in Central America today, where there has been renewed interest in exploring ‘cooperative development’ in the last few years (OIT 2012). In fact, the UN declared the year 2012 as the ‘International Year of Cooperatives’. Additionally, my paper provides important evidence on the long-run impacts of land reforms that reorganised firms from outside ownership. The results are encouraging – they suggest that land reforms that give workers a stake in the production may benefit workers and development.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this column appeared on the the World Bank Development Impact Blog.

References

Engerman, S L and K L Sokoloff (2002), “Factor Endowments, Inequality, and Paths of Development Among New World Economics”, NBER Working Paper No. 9259.

Montero, E (2018), “Cooperative property rights and development: Evidence from land reform in El Salvador”, Harvard University.

Organización Internacional del Trabajo (OIT) (2002), El cooperativismo en América Latina. Una diversidad de contribuciones al desarrollo sostenible, Geneva

Pencavel, J (2013), “The economics of worker cooperatives”, The International Library of Critical Writings in Economics 276.