India should consider how government policies have both intended and unintended consequences for education, as they impact incentives to attend school

The Modi government’s 484-page National Education Policy, released in draft form in June 2019, sets ambitious goals for all levels of Indian education, from early childhood programmes to higher education. In broad terms, the plan calls for increasing public expenditures on education from 10% of government spending to 20% over a ten-year period. It challenges assumptions and pushes for new models to raise education levels throughout the country.

Looking beyond the classroom

For an education policy to succeed, government officials must look beyond the classroom and consider the many factors at play for families, especially those in rural or relatively poor communities. These communities must weigh the costs and benefits of education. While such benefits are obvious to many families of means or those who live in proximity to good schools, for other families, education comes with certain costs. If students are going to school, they are foregoing income – for themselves and for their families – they could earn from working instead.

For many Indian families, the consequential decision of school versus work is shaped by a range of government policies. New research addresses these issues directly and provides useful insights for policymakers as they work to finalise the National Education Policy (Adukia 2019, Adukia et al. 2019).

Do jobs programmes stifle education?

India manages the world’s largest guaranteed jobs programme, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). The programme provides annual employment to adults in 53 million households, nearly one-quarter of all households. Research has shown that the programme raises rural household wages and increases consumption. But is there a cost to education? Some evidence from different developing countries, from Mexico to India, has suggested that an increase in low-skill jobs can induce children to drop out of school at higher rates.

To address this question, I analysed the effect of MGNREGA on children’s educational attainment in rural districts between 2005-09. While there are some negative impacts across districts, the overall negative impact is small in magnitude. For every 43 to 50 households (depending on the particular data source), there is a one-child decline in school enrolment. That number adds up when one accounts for it being 23% of all Indian households, but such declines in enrolment can be mitigated by directing less than 0.35% of MGNREGA expenditure towards education interventions. Further, my analysis shows that increased income from MGNREGA jobs may help some households invest more in their children’s education.

As with many policies meant to achieve one goal, MGNREGA’s impact on Indian households is complex and demands careful analysis. While MGNREGA does result in an increase in school dropout, such a reduction could be offset through targeted education interventions. Further, MGNREGA helps bring millions of Indian households out of poverty. It could also ultimately mean more education for children whose parents have more resources to invest in their education.

Many (but not all) roads lead to education

My related research estimates the effect of rural road building on educational decisions. Does increased access to jobs with higher returns to education improve the educational attainment of rural villagers? Or do the better job opportunities in those larger markets lure young villagers away from school? My colleagues and I examine the impact of new roads that connect villages to the paved road network (Adukia et al. 2019).

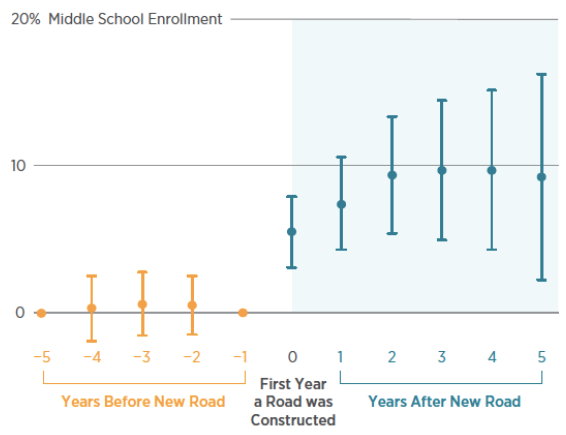

From 2001 to 2015, India built high-quality roads to 115,000 villages, connecting over 30 million rural households to nearby towns and cities. Our research finds that connecting a rural village to a new paved road results in a substantial 7% increase in middle-school enrolment over the following three years as shown in Figure 1. Beyond enrolment, we find improvements in student performance, as more middle-school students took completion exams and scored at a higher percentage.

Figure 1 Impact of roads on middle school enrolment: Treatment effect time series

Notes: This figure shows that increases in school enrolment correspond to the timing of new road construction, and these effects appear to be persistent. The timing and persistence of this change in enrolment suggests that the treatment effects are not driven by labour demand shocks from road construction itself, which would occur as the road is built and then would disappear thereafter. See full paper for details.

We draw from a model of human capital investment to conceptualise the potential link between roads and education:

- On one hand, new roads can offer connections to employment opportunities that raise the wages of low-skilled workers and, thus, increase the opportunity cost of staying in school.

- On the other hand, connections to better job markets could increase the skill premium and actually stimulate more education.

- Better jobs outside the village could raise family income or decrease liquidity constraints, reducing the pressure on children to work.

All of these effects are potentially important, but the labour markets to which villages are connected have the largest effects on schooling decisions. We find positive and significant effects of roads on educational attainment for 39% of the villages.

In the end, there is evidence that connecting those who live in rural and relatively poor markets with nearby cities (mostly) increases educational investment. Put simply, better economic opportunity can be a powerful force for increasing school enrolment and student performance in low-income countries.

Policy implications: The importance of cost-benefit analysis

Our results arrive at an important time for India, as government officials charged with weighing the cost-benefit of India’s guaranteed jobs programme are reportedly paying particular attention to the supposed negative effects on education. However, this new research reveals that efforts to raise families out of poverty should not be sacrificed to misperceived losses in education. Likewise, poor residents of rural villages should not be kept economically isolated out of fear that new and better roads will induce students to drop out of school and pursue immediate work opportunities. India’s example can also offer lessons for developing nations around the world, and reflects the strong linkages between education, growth, and access to markets.

References

Adukia, A (2019), “Spillover impacts on education from employment guarantees,” Becker Friedman Institute, BFI Working paper, University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy.

Adukia, A, S Asher, P Novosad (2019), “Educational Investment Responses to Economic Opportunity: Evidence from Indian Road Construction,” Becker Friedman Institute, BFI Working paper, University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy.