Subsidies of household electricity prices in India come at the expense of firms, reducing both growth and output

Electricity constraints are pervasive in developing countries and can present a barrier to growth. In the most recent World Bank enterprise surveys, over a third of firms in developing countries identified electricity as a major obstacle to their operations (World Bank 2020). While there has been steady progress in electrification rates, one in ten people worldwide still do not have access to electricity, almost all of whom live in developing countries (International Energy Agency 2020). Even with increased electrification rates, outages are prevalent. Almost 60% of firms in developing countries report experiencing an outage in a given year, with an average of over five outages per month, each lasting almost five hours (World Bank 2020). While several papers have studied the impacts of electrification and outages on firms (for example, Allcott et al. 2016, Chaurey and Le 2020, and Fried and Lagakos 2020 ), there has been relatively little work on another constraint faced by firms: electricity pricing.

Cross-subsidisation and high electricity prices for firms in developing countries

Firms in developing countries tend to face relatively high prices for electricity as a result of cross-subsidisation systems whereby firms subsidise prices for other users. In a recent paper (Abeberese 2017), I explore the implications of these high electricity prices for firms. I conduct my analysis on manufacturing firms in India where a system of cross-subsidisation, driven in part by politicians’ incentives to cater to their voting blocs and, to a lesser extent, the social objective of providing affordable services for the poor, has led to relatively low electricity prices for farmers and households at the expense of industrial users. In contrast, in most developed countries, industrial users typically pay lower prices for electricity compared to other users because the cost to power utilities of supplying electricity to industrial users tends to be lower than that of other users due to their ability to receive electricity at higher voltages and in bulk.

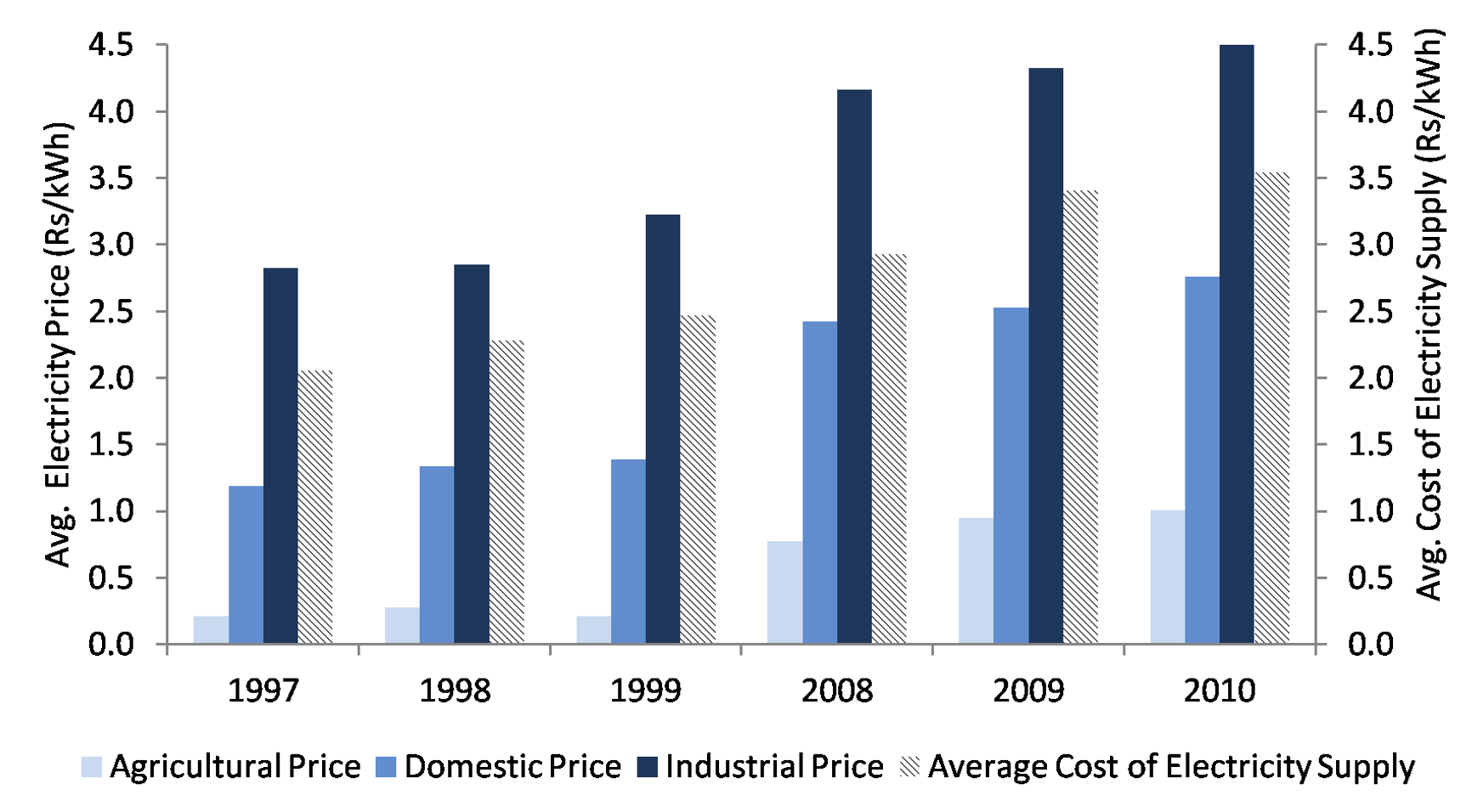

Figure 1 shows the average prices of electricity paid by three categories of users in India: households (domestic users), agricultural users, and industrial users. The prices paid by industrial users have consistently been higher than those paid by domestic and agricultural users. At one point, industrial users paid 15 times the electricity price paid by agricultural users (Government of India 2002). Moreover, although the cost to power utilities of supplying electricity to industrial users is typically lower than that of other users, the prices paid by industrial users in India have consistently been above the average cost of electricity supply. On the other hand, the prices paid by domestic and agricultural users have consistently been below the average cost. At present, the government is in the middle of a reform to reduce cross-subsidies, but progress has been slow and high levels of cross-subsidies still exist.

Figure 1 Average electricity price for different categories of users and average cost of electricity

Source: Government of India (1999, 2002, 2011) and Indiastat Database.

Analysing the impacts of electricity prices

To understand how the relatively high electricity prices may affect firms, I analyse whether changes in electricity prices in a state translate into changes in the behaviour of firms in that state. To isolate the causal effects of electricity prices, I analyse drivers of changes in electricity prices that themselves do not directly affect firms – that is, the only effect on firm behaviour is indirectly through their effect on electricity prices. Since electricity generation in India is primarily via coal-fired thermal plants, the historical prevalence of coal-fired plants in a state together with changes in the price of coal provide variation across states and over time in electricity prices. The prevalence of coal-fired power plants is largely determined by a state’s proximity to coal mines. As this proximity is constant over time for each firm, it should not directly drive changes in firm behaviour. Coal prices paid by power utilities, however, are set by the government-owned coal producers. These prices are separate from and independent of the coal prices paid by firms that use coal as an input and, hence, should also not directly drive changes in firm behaviour.

Higher electricity prices are reducing firm output and productivity growth

Using the resulting electricity prices generated by the variation in the prevalence of coal-powered plants and changes in coal prices, I find that firms reduce their electricity consumption and switch to less electricity-intensive production processes in response to an increase in electricity prices. While self-generation of electricity is a common response to electricity outages, I find that firms do not increase self-generation in response to an increase in electricity prices. This is because self-generation is a substantially costlier alternative to purchasing electricity from power utilities due to the economies of scale in electricity production and the costlier fuels used in self-generation. Therefore, with self-generation not being a viable alternative, the increase in electricity prices leads to a reduction in the overall consumption of electricity by firms.

Since electricity is a critical input for many manufacturing processes, in particular more technologically advanced ones, a reduced ability to use such processes may negatively affect firm growth. In line with this, I find that an increase in electricity prices leads to reductions in firm output and productivity growth rates.

To put the losses from high electricity prices into context, I use the estimates from my analysis together with data on the cost to firms of electricity subsidies for agricultural and domestic users in India from 2008. I find that reducing the amount of these subsidies by as little as 10%(equivalent to about INR 8.9 billion ), could reduce electricity prices for firms by about 1.4%, resulting in an increase in output of about 2%. This increase in output is about INR 140 billion , which would have been more than enough to offset the INR 8.9-billion-reduction in subsidies.

Policy implications

Subsidies aimed at reducing electricity prices for households are not exclusive to India. They are common across developing countries, leading to an inefficient distribution of electricity (Burgess et al. 2020). These subsidies are usually at the expense of firms which, as my study shows, can lead to reduced output and productivity growth rates. Therefore, while increasing electrification and reducing outages can be critical for growth, attention also needs to be paid to reducing distortions in electricity pricing. More efficient pricing systems need to be developed that meet the social objective of assisting poor households without undermining firm growth.

References

Abeberese, A B (2017), “Electricity Cost and Firm Performance: Evidence from India”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 99(5): 839–852.

Allcott, H, A Collard-Wexler and S D O’Connell (2016), “How Do Electricity Shortages Affect Productivity? Evidence from India”, American Economic Review, 106(3): 587–624.

Burgess, R, M Greenstone, N Ryan and A Sudarshan (2020), “The Consequences of Treating Electricity as a Right”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(1), 145-69.

Chaurey, R and D T Le (2020), “Rural Infrastructure Development and Economic Activity”, Working Paper.

Fried, S and D Lagakos (2020), “Electricity and Firm Productivity: A General Equilibrium Approach”, NBER Working Paper No. 27081.

Government of India (1999), Annual Report on the Working of State Electricity Boards and Electricity Departments 1999, New Delhi: Government of India, Planning Commission.

Government of India (2002), Annual Report on the Working of State Electricity Boards and Electricity Departments 2001 – 2002, New Delhi: Government of India, Planning Commission.

Government of India (2011), Annual Report on the Working of State Electricity Boards and Electricity Departments 2011 – 2012, New Delhi: Government of India, Planning Commission.

International Energy Agency (2020), “SDG7: Data and Projections”.

World Bank (2020), Enterprise Surveys.