Demonetisation in India in December 2016, whilst not reflected in official GDP, led to temporary reductions in employment, output, and credit

Economists continue to debate the role of money in society, in part because large-scale experiments concerning money remain rare (Ramey 2016). One such natural experiment occurred in 2016, in an episode known as India’s ‘demonetisation’. On 8 November at 8:15pm local time, Prime Minister Narendra Modi gave an unscheduled, nationally televised address in which he announced that, to combat black money, the two largest denomination notes – the 500 rupee ($7.50) and 1,000 rupee ($15) notes – would cease to be legal tender, effective at midnight. Holders of these notes could deposit them at banks but could not use them in transactions. The notes would be replaced by new 500 and 2,000 denomination notes.

The difficulty of printing new notes quickly meant that currency in circulation that could be used for transactions declined sharply, and only recovered after several months. Demonetisation occurred in an otherwise stable macroeconomic environment and did not affect other hallmarks of monetary policy such as the overall liabilities of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) or the target interest rate. Moreover, eventually more than 99% of the demonetised currency was converted into deposits (RBI 2018), so broader monetary aggregates did not change.

Analysing the consequences of India’s demonetisation

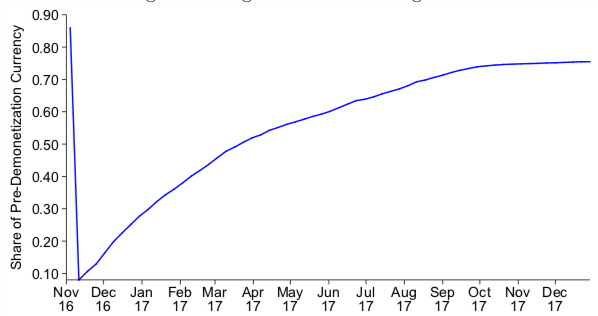

In a recent paper, my coauthors Gita Gopinath, Prachi Mishra, and Abhinav Naryanan and I analyse this episode (Chodorow-Reich et al. 2019). Figure 1 shows the path of large legal tender notes as a share of total pre-demonetisation currency outstanding. Together, these notes accounted for about 86% of currency outstanding. At the time of the announcement, the government had printed new notes equal to about 10% of the pre-demonetisation stock of currency, so that total currency usable as legal tender declined by 75% overnight.

Figure 1 Large-denomination legal tender

We study the consequences of demonetisation in the cross-section of Indian districts (roughly 600 districts partition the country). Using a comprehensive data set from the RBI, we construct a local area demonetisation shock as the ratio of post-demonetisation to pre-demonetisation currency in each month. This approach recognises that, while extreme, at a national level the demonetisation episode constitutes only a single observation, and other economic shocks may have occurred during the period. On the other hand, it creates a challenge insofar as official, high frequency measures of economic activity at the district level do not exist. We combine data from several sources, including (i) ATM withdrawals; (ii) satellite data on human generated nightlight activity, a proxy for economic output used in many circumstances where official data do not exist (Henderson et al. 2012); (iii) a new survey-based measure of employment; (iv) e-wallet and debit card transactions; and (iii) deposit and credit growth.

Demonetisation had different effects across districts

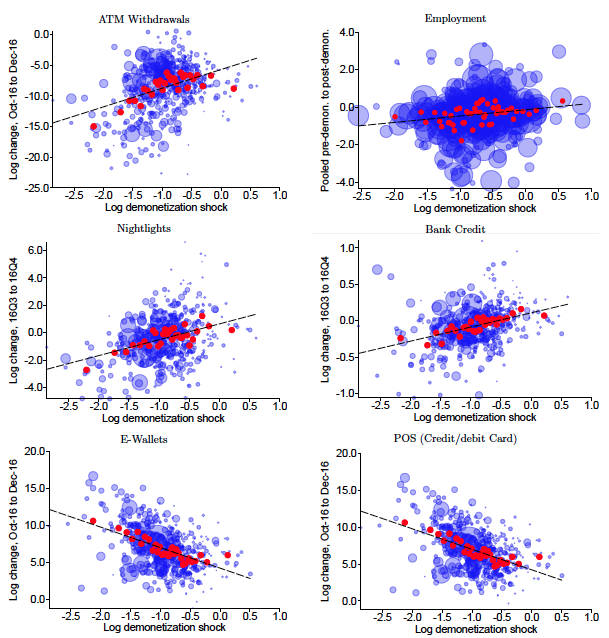

Figure 2 summarises our main results. While essentially all districts experienced a contraction in cash in the period following demonetisation, there was significant variation across districts.

Figure 2 Impact of demonetisation across districts

We find that districts that experienced more severe demonetisation shocks had:

- larger contractions in ATM withdrawals;

- larger reductions in economic activity, as measured by satellite data on human generated nightlight activity and a survey-based measure of employment;

- slower credit growth; and

- faster adoption of alternative payments technologies such as e-wallets and point-of-service cards.

These cross-sectional patterns reject the neutrality of money during India's demonetisation. What this means is that real variables, namely employment and output, were affected by a change in the stock of money. The neutrality of money predicts only nominal variables (e.g. prices and wages) to be affected by a change in the stock of money.

Our findings also shed light on the special role of currency in modern India. During demonetisation, broad money aggregates did not change, but output nonetheless fell. However, the cross-sectional difference in output implied by these figures is vastly smaller than the decline in currency itself. This difference suggests that individuals found ways around using legal tender currency to conduct transactions, for example by convincing retailers to open an informal line of credit, accepting old notes or by switching to electronic forms of payment. Our analysis illustrates two such forms of substitution, towards e-wallet payments and debit cards.

National effects of demonetisation

The cross-sectional responses cumulate to a contraction in employment and nightlights-based output due to the cash shortage caused by demonetisation of three percentage points in December 2016 relative to if demonetisation had not taken place. This magnitude translates into a decline in the growth rate in 2016Q4 (year-over-year) of two percentage points relative to if demonetisation had not taken place. Similarly, the effect on credit implies the currency contraction reduced the quarterly growth rate of credit by two percentage points in 2016Q4.

These effects peak in the months immediately after demonetisation and dissipate over the next few months. The decline inferred from the cross-sectional approach exceeds the actual decline in official GDP during the period. An advantage of our approach is it relies on measures such as nightlight activity and survey employment that capture informal sector activity. In contrast, official GDP does not depend on high frequency measures of informal sector activity, a point acknowledged by the government itself (CEA 2017).

Broader implications

While certainly a unique episode, the lessons from demonetisation may apply to other settings. For example, what economic costs would result from a country leaving the euro and having to print new national currency? Or, in a country such as Sweden that already largely uses electronic payment media, what would happen if the national payments network were to suffer an outage? Our results point to the possibility of substantial economic disruption in these events.

Finally, while our research focuses on the short-term impact of demonetisation, there may be potential longer-term benefits from improvements in tax collections, a shift towards savings in non-financial instruments, and non-cash payment mechanisms. Even in the short run, demonetization may have had effects at the national level which our cross-regional analysis will not uncover, such as moving economic activity from the informal to the formal sector. An emerging literature is already addressing these and other questions.

References

CEA (2017), Economic Survey 2016–17 Volume I chap. Economic Outlook and Policy Challenges, 1–37. Ministry of Finance.

Chodorow-Reich, G, G Gopinath, P Mishra and A Naryanan (2019), “Cash and the economy: Evidence from India’s demonetisation”, Working Paper.

Henderson, V, A Storeygard and D Weil (2012), “Measuring economic growth from outer space”, American Economic Review 102(2): 994–1028.

Ramey, V (2016), “Chapter 2 - Macroeconomic shocks and their propagation”, in Handbook of Macroeconomics, eds. Taylor, J and H Uhlig, 2:71 – 162, Elsevier.

Reserve Bank of India (RBI) (2018), Annual Report 2017-18.