Subsidy policies combined with financial education can generate learning from experiences and promote long-run insurance take-up

Households face different types of risks that can generate large fluctuations in income and consumption. To shield individuals from such risks, many governments have made great strides in developing and marketing formal insurance products. However, in both developing and developed countries, the value placed by individuals on insurance is usually surprisingly low (Finkelstein et al. 2019), with initiatives to provide information, offer subsidies, and increase trust having had limited success (Cole et al. 2013, Banerjee et al. 2019). Many countries have consequently given up trying to sell insurance and moved to make insurance free or mandatory.

One reason why learning about insurance is difficult is that ‘positive’ experience with insurance only happens when there is a negative shock, which is rare. Moreover, the insurance literature has shown that even learning from these bad events is imperfect, as their influence diminishes over time (Cai and Song 2017). The reality, however, is that we know little about the design of policies that can induce effective learning from experiences with insurance.

Combining subsidy policies and financial education

To make progress on these issues, we study the case of a new index-based weather insurance product for rice farmers in China. We set up a novel experiment where we jointly introduce two interventions: a subsidy policy to encourage early adoption and personal experience, and a financial education programme on how insurance works. We track subsequent adoption after two and four years to measure the short- and long-term impacts of the two policies, their interactions, and mechanisms.

The experiment involved 134 villages with about 3,500 households in rural China. In the first year, we randomised subsidy policies at the village level by offering either a partial subsidy of 70% of the actuarially fair price or a full subsidy. We also offered a financial education program about insurance products to randomly selected households in 86 randomly selected villages. In the second year, we randomly assigned eight prices to the product at the household level, with subsidies ranging from 40% to 90%.

Short-term effect of subsidies on insurance take-up

We find that households receiving a full subsidy in the first year exhibit greater demand for insurance in the second year. Since insurance is an experience good, the effectiveness of a subsidy depends crucially on farmers’ experience with the product. For this, we explore the impact of an important element of farmers’ experience with the insurance program: whether they received a payout (direct experience effect) or observed friends receiving payouts (social experience effect), on future insurance adoption.

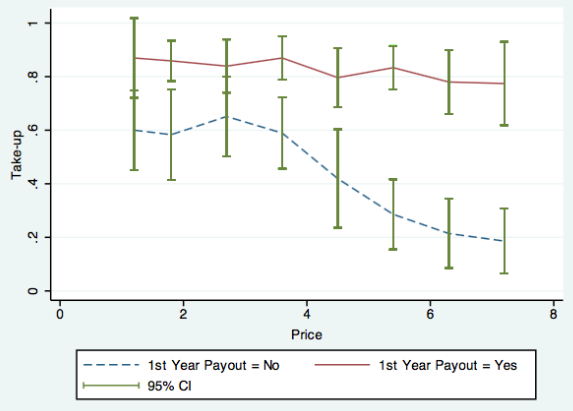

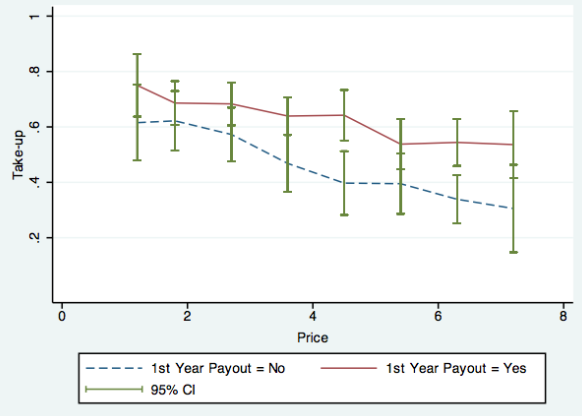

- First, we find that directly receiving a payout has a positive effect on second year take-up, and that it makes insurance demand less price elastic. This effect is stronger for households that paid for insurance (Figure 1). To explain why the payout effect is smaller under the full subsidy policy, we show that people paid less attention to the payout information if they received the insurance for free.

Figure 1 Effect of receiving a payout on second year insurance take-up

(a) Non-free villages

(b) Free villages

- Second, for those not insured in the first year, we find that observing payouts in their network increases their second-year demand.

Together, these results suggest that the impact of subsidies on insurance take-up comes through its potential in increasing the opportunity of receiving or observing payouts (scope effect), although with a trade-off in that the payout effect itself is lower when the insurance was received for free (attention effect). The scope–attention trade-off is made more complex by the fact that paying for insurance when there is no subsequent payout creates a strong discouragement effect, diminishing take-up the next year. We find, however, that there is no price anchoring effect with the use of subsidies wherein lowering the current price would undermine future demand. All in all, the scope effect of subsidies on payouts dominates tradeoffs in increasing take-up.

Long-term effect of subsidies and financial education on insurance take-up

Turning to the long-term effect of observing payouts, with four years of insurance take-up and payout data, we show that there is heterogeneity depending on farmers’ initial level of financial literacy. Specifically, for randomly selected households that benefited from financial education in the first year, receiving a payout provides a one-time learning effect which influences their take-up permanently. For them, experiencing payouts reinforces their understanding of how insurance works and its benefits. In contrast, for households that did not benefit from financial education, such learning does not occur. They update insurance take-up decisions yearly based on recent changes in experience with disasters and returns of purchasing insurance. In that case, subsidies would need to be continuously provided to maintain a good overall take-up rate if no disaster happened.

Conclusion and policy implications

Results from this long-term field experiment and the contents of the financial education dispensed suggest a new explanation as to why promoting the take-up of insurance has proven to be so difficult. The stochastic nature of weather shocks and of the resulting payouts creates salience each year on either the cost or the benefit of insurance, making it difficult for farmers with low financial literacy to fully understand the overall benefit of the product.

The policy implication is that in order to make a subsidy policy effective in promoting long-term voluntary insurance adoption, it should be combined with other interventions such as financial education to improve households’ initial understanding of insurance, so they have the capacity to learn from experiences with the product. This insight could be widely applied to the take-up of other products and activities that involve uncertainty and require time to experience gains or losses.

References

Banerjee, A, A Finkelstein, R Hanna, B Olken, A Ornaghi and S Sumarto (2019), “The challenges of universal health insurance in developing countries: Evidence from a large-scale randomized experiment in Indonesia”, NBER Working Paper 26204.

Cai, J and C Song (2017), “Do disaster experience and knowledge affect insurance take-up decisions?”, Journal of Development Economics 124: 83–94.

Cai, J, A de Janvry and E Sadoulet (2020), “Subsidy policies and insurance demand”, American Economic Review, forthcoming.

Cole, S, X Giné and J Vickery (2017), “How does risk management influence production decisions? Evidence from a field experiment”, The Review of Financial Studies 30(6): 1935–70.

Finkelstein, A, N Hendren and E Luttmer (2019), “The value of medicaid: Interpreting results from the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment”, Journal of Political Economy 127(6): 2836–74.