Tax policies that reduce firm inaction are more effective at stimulating investment than policies that simply lower the cost of investment

One of the most important changes in the public finances of developing countries has been the wide adoption of value added taxes (VATs) (Ebrill 2001). VATs are popular because they allow governments to raise revenue. It is also thought that they do not distort production. While this may be true in theory, different approaches to VAT systems around the world expose their potential to induce distortions in firm production decisions.

The study: China’s tax reform and firm investment

In a recent paper (Chen et al. 2019) we study the Chinese VAT system as an example of an approach that discouraged investment. Historically, China’s VAT system did not credit firms for VATs paid on equipment purchases. In the 2000s, the Chinese government introduced a reform to remove this tax on investment.

We study the effects of this reform on firm investment incorporating the universal fact that investment is lumpy. Investment is said to be lumpy because it either takes the form of inaction (when firms do not invest) or a spike (when firms replace a considerable fraction of their existing capital stock). While the lumpiness of investment is a known fact, policymakers do not usually consider how tax policy can impact lumpy investments.

The findings

Tax policy and lumpy investments

We find that tax policies can directly impact the lumpiness of investment. China’s VAT reform exposes the importance of investment frictions because it had two effects on investment. First, it reduced the tax cost of investment by 15%. Second, it narrowed the price gap between new and used equipment, which directly impacts the decision to invest or not.

Our results show that firms that were affected by the policy increased investment by 36% relative to a set of control firms. In addition, we find that the majority of this increase in investment is driven by additional spikes. This result suggests that interactions between tax policy and investment frictions were a major contributor to the investment increase.

Capital value and delayed investment

Before 2004, China had a production-based VAT system. This meant that firms did not receive input credits for equipment purchases, in contrast to other expenses such as materials. For example, a firm purchasing equipment worth 1,000 renminbi (RMB) would need to pay RMB 1,170 in total, given the 17% VAT rate. If the firm later sold this equipment in the used market, it would not recover the additional VAT.

This system increased the gap between the price of new and used capital (‘partial irreversibility’). (Cooper and Haltiwanger 2006). Partial irreversibility can lead firms to delay investments since they may only want to adjust their capital levels when they face sufficiently high or low productivity shocks. In our data, this delay is evident in the fact that almost half of the firms do not invest in a given year.

Further analysis: Foreign versus domestic firm impacts

Starting in 2004, the Chinese government started transitioning to a VAT system that did not discourage investment. The government first piloted the new system in Northeast China (Cai and Harrison 2018). This system was unexpectedly adopted nationwide as a response to the financial crisis.

Since foreign firms had been allowed to deduct input VAT on equipment even before the reform, the reform generated a natural experiment. That is, the 2009 VAT reform did not affect the tax treatment of investment for foreign firms, but it substantially reduced investment costs for domestic firms. For this reason, we use foreign firms as controls for treated domestic firms in our difference-in-difference analysis.

The findings

Domestic firm investment

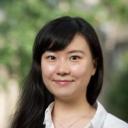

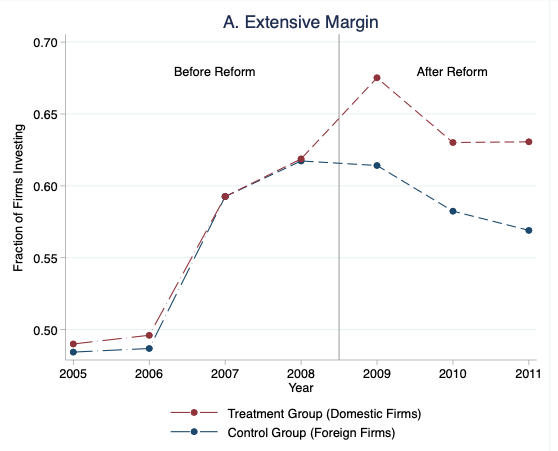

We find that the VAT reform significantly increased the investment of domestic firms at both the extensive and intensive margins. We first consider the extensive margin — whether a firm invests or not. Panel A of Figure 1 plots the fraction of domestic firms (red line) and foreign firms (blue line) investing in any given year. This figure shows that foreign firms had similar investment trends before the reform.

After the reform, however, the fraction of domestic firms with positive investment increased by around 5 percentage points, or 10% relative to the 50% average rate. Similarly, panel B shows that the investment to capital ratio of domestic firms rose by 3.6 percentage points, for a 36% increase relative to an average investment rate of 10%.

Figure 1 The effects of 2009 China’s VAT reform

Domestic firm spike investment

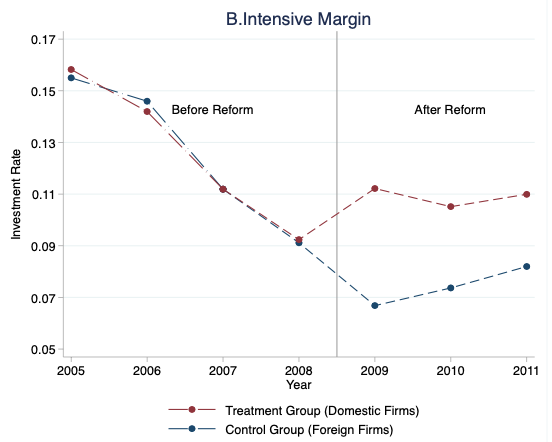

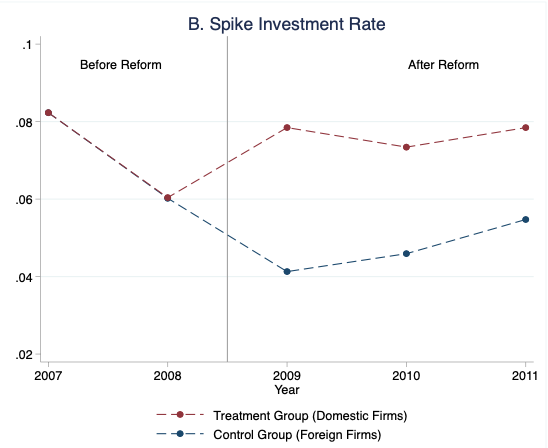

We delve into the effects of the reform by studying whether firms increase the size of planned investments or whether they opt to make new large investments. To do so, we decompose the investment response into ‘spikes’ and ‘non-spikes’. The spike investment rate is the investment rate multiplied by an indicator for whether the firm replaced more than 20% of its capital in a given year. The non-spike captures investments that replace less than 20% of capital.

Panel A of Figure 2 plots the average non-spike investment rate of domestic and foreign firms, respectively. This graph shows that the reform had a limited effect on the non-spike investment rate. In contrast, the reform increased the spike investment rate by 3.5 percentage points for domestic firms. Overall, the spike investment rate is responsible for 90% of the total effect.

Figure 2 Decomposing the effects to spike and non-spike investment

VAT credits and firm investment

An additional feature of China’s VAT system in 2009 was that firms were not immediately refunded if they had excess VAT credits. This feature generates an additional test since firms with excess VAT credits would not be affected by the reform.

We find that firms respond differently depending on whether they have excess VAT credits. Specifically, firms with excess VAT credits show much weaker responses to the reform. This suggests that the refunding policy for excess credits in VAT systems can have implications for firm investment.

Policy implications: Stimulating firm investment

Motivated by our reduced-form results, we construct a dynamic investment model that incorporates salient features of the Chinese tax system. The model is consistent with cross-sectional investment patterns as well as with the reduced-form effects of the reform. The model allows us to study why different policies have different effects on investment.

The model shows the tax policies interact with the investment frictions that generate lumpy investment. Policies that reduce the likelihood of firm inaction are more effective at stimulating investment for a given fiscal cost than policies that simply lower the cost of investment.

For instance, by reducing partial irreversibility, lowering the effect of the VAT rate on equipment is more effective at stimulating investment than a comparable reduction in the cost of capital. Other policies that lower partial irreversibility, such an investment tax credit or eliminating input taxes, are also more effective at stimulating investment than other policies, such as a corporate income tax cut.

While the growth of VAT has increased revenue collections in developing countries, we are just starting to understand how this revolution in tax administration affects firm decisions (e.g. Gadenne et al. 2019, Singh 2019). The case of China’s VAT reform demonstrates that how VAT is implemented can significantly impact firm investment.

References

Chen, Z, X Jiang, Z, Liu, J C S, Serrato and D Xu (2019), “Tax Policy and Lumpy Investment Behavior: Evidence from China’s VAT Reform”, NBER Working Paper 26336.

Cooper, R W and J C Haltiwanger (2006), “On the nature of capital adjustment costs”, The Review of Economic Studies 73(3): 611-633.

Cai, J and A Harrison (2018), “Industrial Policy in China: Some Unintended Consequences?”, Industrial and Labor Relations Review.

Ebrill, L, M Keen, J P Bodin and V Summers (2001), The Modern VAT, International Monetary Fund.

Gadenne, L, N Tushar and R Rathelot (2019), “Taxation and supply chains: Evidence from Value-Added Taxes in West Bengal”, Working Paper.

Singh, D (2019), “Merging to Dodge Taxes? Unexpected Consequences of VAT adoption in India”, Working Paper.