The positive effects of improving management systems persist nine years after management consulting support was provided

Differences in management account for about 30% of the unexplained total factor productivity (TFP) differentials driving the large differences in the wealth of nations (Van Reenen 2018). As a consequence, many governments run programmes designed to help firms improve their management practices. But there is a debate over how long we should expect any improvements to last. One view is that management improvements become self-sustaining, epitomised by the ‘Toyota way’ (Liker 2004). But a contrasting view is that maintaining good management is difficult, and that two-thirds of transformation initiatives ultimately fail (Sirkin et al. 2005).

Study and methodology

In our recent research, we examine the persistence of an intensive management intervention carried out in India (Bloom et al. 2018).

In 2008, we started a randomised experiment involving 28 plants in 17 firms in the woven cotton fabric industry in India. These were large firms, with an average of 270 employees, and a median of two plants per firm.

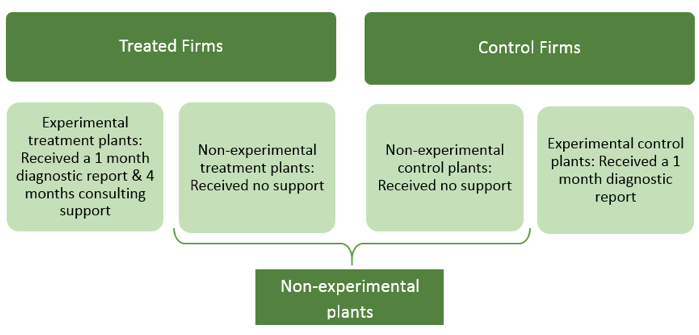

We divided these plants into three groups:

- Non-experimental plants received no diagnostic or consulting support.

- Experimental control plants received a one-month diagnostic that involved evaluating the current management practices of each plant and providing recommendations for change.

- Experimental treatment plants received the one-month diagnostic as well as four months of implementation support, where consultants helped the plant implement as many of 38 standard management practices as they could.

Figure 1

Findings

In the first year after this intervention, we found that experimental treated plants had increased their adoption of these 38 management practices by an average of 38 percentage points (compared to a 12 percentage point increase in the control plants) resulting in improvements in quality, an increase in output, and a 17% increase in productivity.

Did these interventions last?

In 2017, nine years later, we used the original consulting firm and returned to all 17 firms that we had previously measured over the 2008-11 period. We were able to re-measure management practices in both the experimental and non-experimental plants.

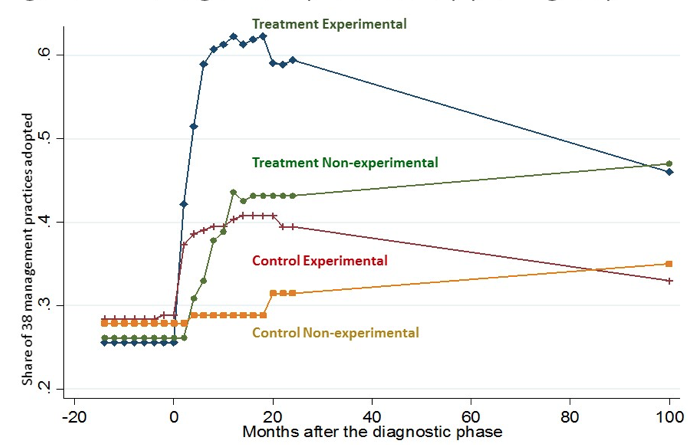

Figure 2 shows that we find something in between the two views noted above:

- Treated firms did drop about 40% of their original gain in management practices

- Control firms also dropped a lot of the practices they had adopted after the diagnostic.

- The result is that there is still a large, persistent and statistically significant 19.7 percentage point gap in management practices between the treatment and control plants, eight to nine years after the experiment ended.

- Over time, the level of management practices converges between the experimental and non-experimental plants within firms – we see this occurring for both the treated firms and for the control firms.

- This convergence also occurs at the individual practice level, with firms transferring the practices they kept in their experimental plants across to their non-experimental plants.

Figure 2 Management practices by plant group

Notes: Sample comprised of the balanced panel of plants from 2008 to 2017 (11 treatment experimental, 6 treatment non-experimental, 6 control and 2 control non-experimental).

What drives changes in management practices?

We interviewed the directors and plant managers about each of the 38 management practices to understand why practices were adopted or dropped over time. The most common reason for adopting a new practice was spill-over from another plant in the same firm.

Within the treated experimental plants, there were three main reasons why practices were dropped:

- The most important, accounting for over half the dropped practices, was a new plant manager coming in.

- The second most important reason was a lack of director time.

Some practices were also dropped because firm owners saw no benefit. This highlights the importance of key employees in maintaining good management.

There were two types of practices that were most likely to be dropped:

- visual displays and written practices that few firms were using before the intervention, and that many firms did not see the value of; and

- practices requiring daily attention from management.

In contrast, we find that many practices are very sticky, with few firms dropping them once adopted. The practices most likely to persist were:

- practices that were relatively common in other firms to begin with; and

- practices most directly tied to the immediate improvements in quality and inventory levels that occurred after the original consulting intervention.

Achieving lasting impacts on firm performance

Our main measure of productivity is looms per worker, a classic measure of productivity for textile firms (e.g. Clark 1987). A higher number indicates fewer breakdowns and a higher rate of production, with less workers needed for fixing machines or quality-related problems.

- We find that this measure increases by 26.7% over the eight to nine years, which is statistically significant.

- Further, there is suggestive evidence that productivity rises over time.

- Finally, using data from our original survey wave, we were also able to impute an increase in labour productivity of 19% since 2011, with a long-run effect of 35%.

Revealed preference also suggests that firms found the management improvements useful:

- Treated firms were more likely to hire consultants on their own after our intervention.

- Treated firms also accompanied the improvement in operational management practices with improved marketing practices.

Hope for the consulting industry, and a spur to public policy

The received wisdom when two of the authors worked at a leading global management consulting firm was that management innovations would last approximately three years. Our work shows the potential for many of the improvements implemented to persist much longer, increasing the expected return to firms engaging such services. These lasting impacts then do raise the puzzle of why more firms do not invest in improving management on their own, and what types of public policy interventions can change this. We see this as an active area for future research.

Editor’s Note: Read more about this project in the IGC’s growth brief.

References

Bloom, N, B Eifert, A Mahajan, D McKenzie and J Roberts (2013), “Does Management Matter? Evidence from India”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(1): 1-51.

Bloom, N, A Mahajan, D McKenzie and J Roberts(2018), “Do Management Interventions Last? Evidence from India”, NBER Working Paper no. 24249.

Clark, G (1987), “Why Isn’t the Whole World Developed? Lessons from the Cotton Mills”, Journal of Economic History 47(1): 141-173.

Liker, J K (2004), The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the World's Greatest Manufacturer, McGraw-Hill.

Sirkin, H, P Keenan and A Jackson (2005), “The Hard Side of Change Management”, Harvard Business Review, October.

Van Reenen, J (2018), "Management and the wealth of nations", VoxDev.org, 18 January.