A 15-year survey of 12,000 firms across 34 countries shows that management practices explain a large share of productivity gaps

Income differences between rich and poor countries remain staggering, and these inequalities are in good part due to unexplained productivity gaps (what economists call total factor productivity, or TFP for short). Many estimates (e.g. Jones 2015) calculate that US productivity is more than 30 times larger than some sub-Saharan African countries. In practical terms, this means it would take a Liberian worker a month to produce what an American worker makes in a day, even if they had access to the same capital equipment and materials.

This huge productivity spread between countries is mirrored by large productivity differences within countries. Output per worker is four times as great, and TFP twice as large, for the top 10% of US establishments compared to the bottom 10%, even within a narrowly defined industry like cement or cardboard box production (Syverson 2011). And such cross-firm differences appear even greater for developing countries (Hsieh and Klenow 2009).

Core management practices

The importance of core management practices for such between-country and between-firm performance spreads has long been recognised, from Adam Smith’s 1776 pin factory, through Francis Walker (the founder of the American Economic Association in 1887), to today’s large community of management scholars.

Many case studies illustrate the importance of management. For example, one I was involved with was Gokaldas Exports (Bloom et al. 2013), a family-owned business founded in 1979 that had grown into India’s largest apparel exporter by 2004. It had 35,000 workers, was valued at approximately $215 million, and exported nearly 90% of its production. Its founder, Jhamandas H Hinduja, had bequeathed control of the company to three sons, each of whom brought in his own son. Nike, a major customer, wanted Gokaldas to introduce lean management practices and put the company in touch with consultants who could help to make this happen. But the CEO was resistant. It took rising competition from Bangladesh, multiple demonstration projects, and finally the intervention of other family members (one of whom I taught in business school) to overcome this resistance. The new practices led to greatly enhanced performance.

Such anecdotes suggest that management is an important driver of productivity, and further raise the question of why – if management is so critical – is change so challenging? However, many remain sceptical. Are such case studies really generalisable? The statistical study of management practices has been inhibited by a lack of large-scale, quantitative data across many firms, industries, and countries. In the past 15 years, I have helped develop new ways of robustly measuring management practices and can now show that a large fraction of productivity differences is due to the adoption of those practices.

World Management Survey

Our first attempt has been the World Management Survey. This now covers 12,000 organisations across 34 countries that use (or don’t use) core management practices, such as setting sensible targets, providing proper incentives, and credibly monitoring performance (Bloom and Van Reenen 2007, Bloom et al. 2017). With this instrument, we rated companies on their use of 18 practices, ranging from poor to non-existent at the low end (for example, “performance measures tracked do not indicate directly if overall business objectives are being met”) to very sophisticated at the high end (“performance is continuously tracked and communicated, both formally and informally, to all staff using a range of visual management tools”). When we started working on this project back in 2002, our aim was to build a dataset that had two key features. First, the data had to be reliable and fully comparable across firms. Second, the data had to cover a large and representative sample of firms around the world. We quickly realised that in order to achieve our goals we had to manage the data collection process ourselves, with the help of a large team of interviewers conducting phone interviews from the London School of Economics, where we were all based at the time. We were able to make many methodological choices in terms of how the data were collected – such as having multiple interviews per firm with different interviewers – which reassure us that the data provides a very realistic perspective of the extent to which the core management practices included in the survey were actually adopted.

Variation across firms and between countries

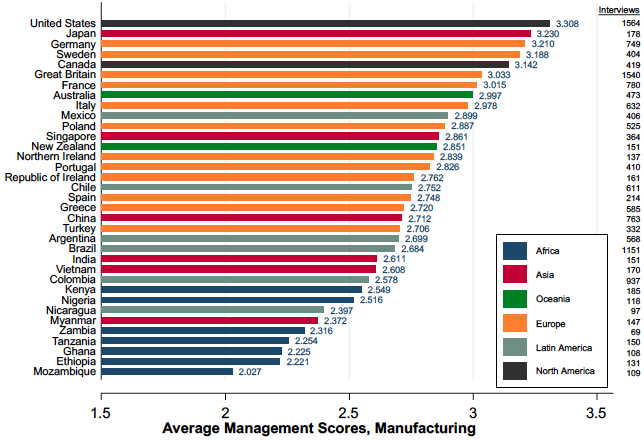

Figure 1 Average management scores by country

Note: Average management scores; 15,489 observations (2004-2014).

Source: Bloom et al. (2017)

The dispersion in the management score across firms is large. Figure 1 shows that there are large between country differences that largely mirror the productivity spread. An even larger fraction of the overall variance (approximately 40%) is actually within countries across different firms (Figure 2). Across our entire sample we find that 11% of firms have an average score of two or less, which corresponds to very weak monitoring, almost no targets for employees, and promotions and rewards based on tenure or family connections. At the other end of the spectrum, there are also clear management superstars across all the countries we surveyed – 6% of the firms in our sample have a score of four or greater. In other words, such firms boast rigorous performance monitoring, systems geared to optimise the flow of information across and within functions, motivational short- and long-run targets, and a performance system that rewards and promotes great employees while helping underperformers to turn around or move on.

Figure 2 Management practice scores across firms

Note: Bars are the histogram of the actual density.

Source: Bloom et al. (2017)

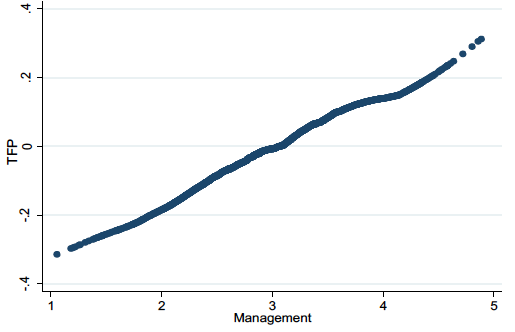

The large, persistent gaps in basic managerial practices that we document are associated with large, persistent differences in firm performance. Better-managed firms are more productive, grow at a faster pace, and are less likely to die. Figure 3 shows a close correlation between better-managed firms and higher productivity. This may not be causal of course, but we also observe these performance improvements after experimental interventions ‘injecting’ these type of management practices into Indian textile firms (Bloom et al. 2013).

We performed a simple accounting exercise to evaluate the importance of management for the cross-country differences in productivity. We found that management accounted for about 30% of the unexplained TFP differentials driving the large differences in the wealth of nations.

Figure 3 Firm TFP is increasing in management

Notes: This plots the lowest predicted valued of TFP against management (bandwidth=0.5). TFP calculated as residual of regression of ln(sales) on ln(capital) and ln(labor) plus a full set of 3 digit industry, country and year dummies controls. N = 10,900.

Source: Bloom et al. (2017)

Concluding remarks

The variation in management is in part due to policy-related factors, starting with competition, which creates a strong incentive to reduce inefficiencies. We have also studied the role of labour regulations, as they may dampen the incentive to adopt practices requiring the flexibility to reallocate employees according to their merit, and to adopt performance-related forms of compensation. Policies aimed at improving the skills, or accelerating the entry or selection of firms based on their managerial capabilities, should certainly be in every policymaker’s playbook.

Finally, information may be critical. As our Gokaldas case study mentioned above illustrated, many firms in developing countries may not even realise how weak their management practices are. Or, even when they do they realise this, they may not know how to improve things. Tools such as benchmarking and training can help spread information and knowledge in both of these dimensions. Governments and NGOs often do this, but such programmes are rarely evaluated in a rigorous way (for a survey, see McKenzie and Woodruff 2017). Doing so may be able to raise management and ultimately the wealth of emerging nations.

Editors' note: This column is based on this PEDL project.

References

Bloom, N and J Van Reenen (2007), “Measuring and explaining management practices across firms and countries”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(4): 1341-1408.

Bloom, N, S Melvin and J Van Reenen (2013), “Gokaldas Exports (A): The challenge of change”, Stanford Business School Case Study SM-213(A).

Bloom, N, B Eifert, A Mahajan, D McKenzie and J Roberts (2013), “Does management matter? Evidence from India” Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(1): 1-51.

Bloom, N, R Sadun and J Van Reenen (2017), “Management as a technology”, CEP Discussion Paper 1433.

Hsieh, C-T and P Klenow (2009), “Misallocation and manufacturing TFP in China and India”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(4): 1403-1448.

Jones, C (2015), “The facts of economic growth”, Chapter 2 in J Taylor and H Uhlig (eds), Handbook of Macroeconomics, Volume 2A, North Holland.

McKenzie, D and C Woodruff (2017), “Business practices in small firms in developing countries”, Management Science 63(9): 2967-2981.

Syverson, C (2011), “What determines productivity?” Journal of Economic Literature 49(2): 326-65.