Artisans who are attached to their creative output offer discounts to discerning buyers, even when these buyers have a high willingness to pay

The developing world is replete with people working in low-income, but creative occupations. Among them, handicraft artisans are the ones we most readily recognise because they imbue their creations with personalisation and intricate craftsmanship. And yet, they often languish in poverty. Artisans create decorative items that offer them scope for creativity and individual expression, such that each of their creations is a labour of love. However, little is concretely known about a crucial element to their businesses – how do they set prices? This is an important question because over 40% of workers in the global economy are employed in creative occupations (Florida 2002) and it is crucial to understand how they monetise their work output.

Intrinsic motivation versus material rewards

Some scholars have argued that individuals engaged in creative work are intrinsically motivated and care less about material rewards (e.g. Deci et al. 1999). In contrast, other scholars have suggested that even people deeply connected with their work may seek competitive returns for their work output. This is especially the case when their economic needs are substantial or when they view economic rewards as validation of their mastery (Bourdieu 1993).

In my paper (Ranganathan 2018), I revisit this important question by studying price-setting among wood and lacquerware artisans in Channapatna, an isolated handicraft town in southern India. I use eight months of ethnographic fieldwork, consisting of observation and interviews with artisans in their natural work environment, and a field audit experiment.

The type of buyer is important to artisans

My fieldwork revealed that creative producers like artisans develop a deep connection with their work and attachment to their products. In interviews, artisans described taking pride in every piece they made and treating each product like their child. They experienced the transformation of the craft products from its raw, crude form to its final, refined state, which instilled identification with the work process. This identification was internally driven, stemming organically from the process of engaging closely with work tasks, in contrast to externally anchored motivations like money or reputation.

My fieldwork further suggested that artisans’ identification with their work influenced how they sold their products and set prices. They valued finding a discerning buyer who would take care of their product, appreciate its value, and display it in aesthetically pleasing ways. In fact, they valued this more than simply finding a buyer who would pay a hefty price. Therefore, when artisans encountered discerning buyers, they de-emphasised financial gains and set below-market prices (even when the buyers had a high willingness to pay). When the same artisans encountered non-discerning buyers who were otherwise similar, however, they tried to maximise their financial gains by setting market prices.

Segmenting buyers

I found that there were three distinct groups used by artisans as a heuristic to determine their level of discernment and to set prices accordingly:

- Indian-baseline buyers. This group includes Indian buyers from the region around Channapatna. They looked and dressed like locals, wearing polyester Indian attire and plastic jewellery, and carrying synthetic handbags. Channapatna’s artisans consider buyers in this group to be non-discerning.

- Indian-craft buyers. This group likewise includes Indian buyers native to the region. However, they wear handmade products, including craft jewellery and hand-woven Indian attire, and carry natural fibre handbags. These buyers signal appreciation for handmade products and are seen as discerning by artisans.

- International buyers. As the name suggests, this group consists of foreign tourists who choose to shop for handmade products in the remote town of Channapatna. These buyers conduct their transactions in English, look discernibly wealthy, have lighter skin colour than other buyers, and wear Western clothing. Artisans see them as having a keen interest in Indian handicrafts and therefore consider them discerning.

Having uncovered these three categories of buyers, I next implemented an experiment that captured artisans’ pricing pattern across these different buyer groups. The experiment also compared artisans’ prices with the prices of traders, who did not make the products that they sold. In this way, I could analyse how artisans’ prices to different buyers deviate from standard market pricing.

Designing the experiment

I used a field audit design to study price setting in Channapatna. Six auditors, who varied in their portrayed level of discernment, were trained to act as buyers of a pair of half-inch bangles. Each auditor visited 77 sellers (52 artisans and 25 traders) in a randomly assigned order. They made purchases and negotiated for a price according to a prescribed bargaining script. The experiment therefore provided data on the prices charged by artisans and traders to different buyers from 455 sales transactions.

The auditors differed in their material presentation, which constituted the key aspect of the experiment, as follows:

- Two Indian-baseline auditors came from towns around Channapatna and conducted their transactions in the local language. They dressed like they normally would.

- Two Indian-craft auditors also came from towns around Channapatna. However, they were given hand-woven cotton clothes to wear along with terracotta earrings, a handcrafted metal necklace, and a handmade bag.

- Two international auditors, from Thailand and Mauritius, looked and dressed like foreigners and conducted their transactions in English.

Prices vary according to the buyer

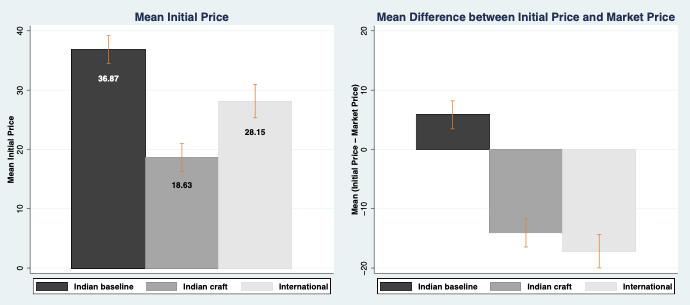

The results are shown in Figure 1, which compares artisans’ prices for the three buyer categories, and the market price for each buyer category.

Figure 1

The graph on the left indicates that artisans charged the lowest prices to the Indian-craft buyers (18.63 INR), followed by the international buyers (28.15 INR). They charged the highest prices to the Indian-baseline buyers (36.87 INR). The graph on the right shows that artisans offered prices significantly below market prices to the two discerning buyer categories, Indian-craft and international. With respect to the non-discerning Indian-baseline buyers, they offered prices slightly greater than the market price.

This suggests that artisans offer discerning buyers significant discounts (up to 50%) for their products. Further, these discounts are surprisingly offered to even those buyers who were willing to pay more for the products, such as foreigners.

Policy implications: Increasing tourism may not raise income for artisans

Artisans in Channapatna, despite being poor, identify strongly with their work. They monetise their work output in accordance with the audience consuming it, offering significantly below-market prices to discerning audiences.

My findings highlight the need for more sophisticated models of how low-income workers make sense of their work. These must go beyond theories rooted solely in financial interests. For example, my research implies that a common policy solution to help artisans increase their income, increasing tourism to artisanal towns, may not be effective. This policy makes sense in theory, as more tourists lead to more sales and therefore more income. However, in practice, artisans sell their products at heavily discounted prices to foreign buyers, meaning their income does not increase in a meaningful way.

References

Bourdieu, P (1993), The field of cultural production: Essays on art and literature, New York: Columbia University Press.

Deci, E, R Koestner and R Ryan (1999), “A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation”, Psychological Bulletin 125: 627–668.

Florida, R (2002), The rise of the creative class: And how it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life, New York: Basic Books.

Ranganathan, A (2018), “The artisan and his audience: Identification with work and price setting in a handicraft cluster in Southern India”, Administrative Science Quarterly 63: 637–667.