A new experiment in Mozambique found that the social stigma attached to HIV has been falling, but people do not tend to realise it. A simple message that informed individuals of their communities’ true (low) degrees of stigma substantially increased HIV testing.

By 2020, only 84% of the global HIV-infected population knew their status, failing the United Nations 90-90-90 goal. Insufficient status awareness imposes extraordinary challenges to preventing transmission and expanding medical treatment. Promoting HIV testing is crucial to overcoming this challenge (WHO 2020, Granich et al. 2009), especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, which remains the world’s most HIV-affected region.

Social stigma is a widely blamed barrier to the global efforts to fight HIV/AIDS

Social stigma is a widely blamed demand barrier to all HIV-related care (Stangl et al. 2013, Stangl, Brady, and Fritz 2012). People living with HIV are often morally judged and socially avoided. Seeking a test for HIV and initiating and adhering to treatment could all enact stigma (Derksen et al. 2022, Lowerther et al. 2014, Thornton 2008). Such stigma spills over to their families and extends to those at high risk of infection.

However, there is a shortage of well-identified evidence on the causal effect of stigma on HIV care. Is stigma's impact real and substantial enough for us to act on, or is stigma a convenient scapegoat covering failures in other aspects of the healthcare system?

Stigma and HIV healthcare in Mozambique

Stigma is a community feature and is always intertwined with other community features such as culture, economic development level, population knowledge, social coherence, etc. It is challenging to tease out the impact of stigma on behaviour from all other social factors associated with stigma. My recent research (Yu 2023) in Mozambique took on this challenge and provided direct insight into the role of stigma in HIV health care.

Stigmatising attitudes towards HIV have been falling in Mozambique

The study team first conducted a baseline survey in 2018 on a representative sample of households in 76 Mozambican communities. Among other information, we collected responses to the following three questions to measure the stigma environment.

- Would you buy fresh vegetables from a shopkeeper if you knew that this person had HIV? (Yes/No)

- If a member of your family became sick with AIDS, would you be willing to care for them in your own household? (Yes/No)

- In your opinion, if a teacher has HIV but is not sick, should they be allowed to continue teaching at school? (Yes/No)

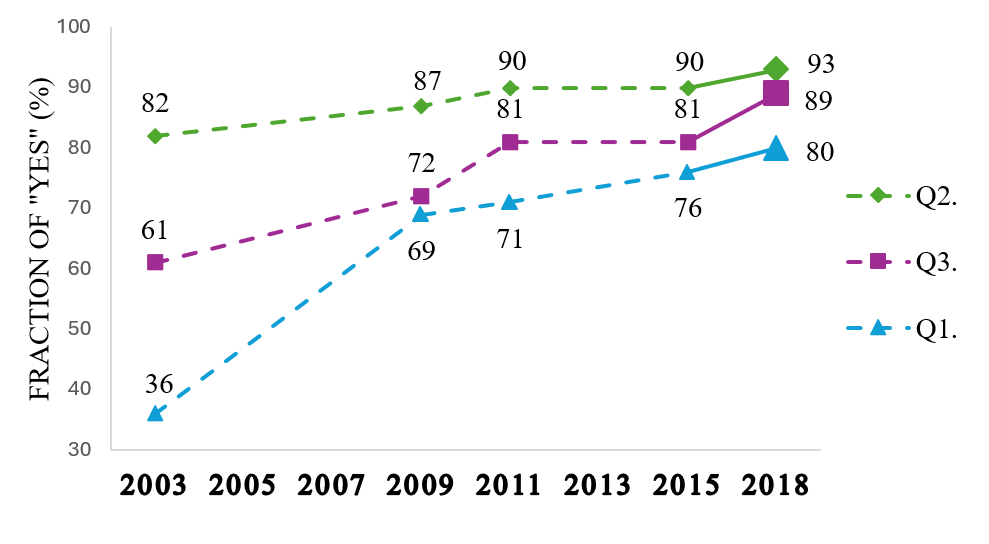

The three questions were adopted from the worldwide panel AIDS Indicator Survey (AIS) of the DHS Program. An affirmative answer indicates a supportive attitude, while a negative answer indicates stigmatisation. An average community in the 2018 survey gave high shares of affirmative answers to the three questions - 80.1%, 93.2%, and 89.2%, respectively. This finding echoes the results from a representative Mozambican sample by AIS: Figure 1 depicts the share of affirmative answers from AIS consistently increased steadily from 2003 to 2015 (MISAU, INE, and ICF 2015) and from our baseline survey in 2018.

Figure 1: Answers to questions on the stigma environment show supportive attitudes are increasing

Many people do not realise that HIV-related stigma is falling

We revisited the surveyed households one year later, in 2019, and collected their beliefs about the stigma environment of their community. For example, we asked,

- If I ask the question, “Would you buy fresh vegetables from a shopkeeper if you knew that this person had HIV?” to 10 people in your community, how many of them would you expect to say “Yes”?

If 90% of the community said “yes" in the baseline survey when asked if they would buy fresh vegetables from an HIV-positive shopkeeper, but a participant believed that only 7 out of 10 would have said “yes," she overestimated the stigma. Sixty-three percent (63%) of the survey participants overestimate at least one of the stigma measures in their community.

Correcting misperceptions amongst the misinformed population

We embedded an experiment during the 2019 revisit survey. Those who overestimated stigma were randomly assigned to one of the following groups:

- Control group - participants received a coupon redeemable for 50 meticais ($2.25 by PPP) when taking an HIV test

- Concern-relieving group - participants received the same 50-metical coupons as the control group and were informed of the true (low) stigma environment measures from their communities

- High-incentive group - participants received coupons redeemable for 100 meticais upon taking a test but received no information.

The primary outcome of interest is HIV-testing behaviour measured through the redemption of coupons.

HIV testing services are free and anonymous at local sanitary units and typically take 30 minutes, including waiting time. Coupons we distributed in the experiment could be redeemed in the local sanitary unit for their value in electronic cash when a person presented proof of an HIV test (without disclosing the test result). The coupons were valid for 14 days. A unique barcode, readable only by researchers analysing data remotely, can link a redeemed coupon to its recipient. This protocol keeps the test takers anonymous to research staff in the field.

A simple message that informed individuals of their communities’ true (low) degrees of stigma substantially increased HIV testing

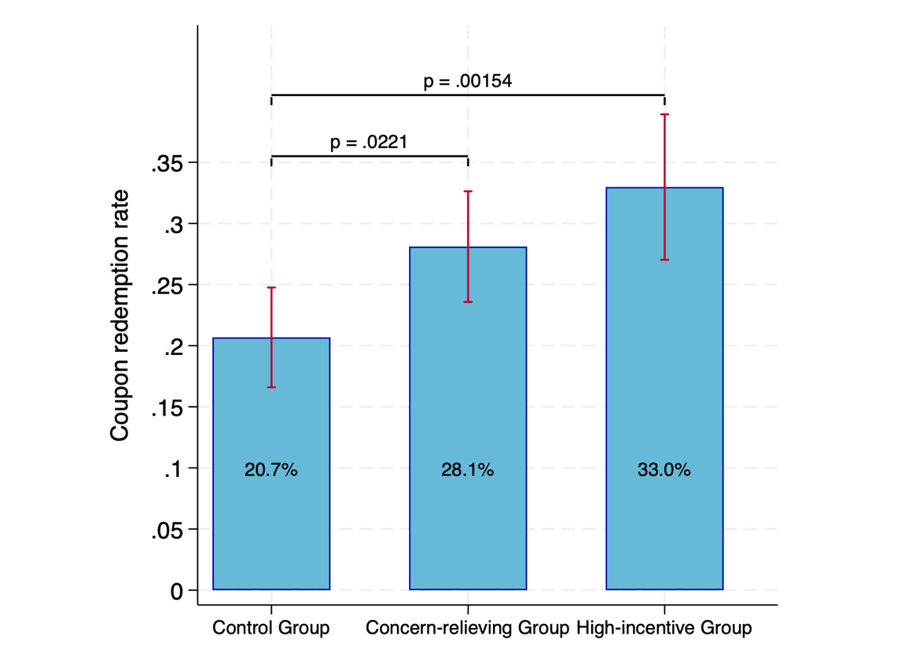

In the control group, 20.7% of participants took tests. The concern-relieving intervention increased the testing rate by 7.4 percentage points (or 36%) while doubling the financial incentives increased the testing rate by 12.3 percentage points (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Informing individuals about the true stigma environment increased testing

The treatment effect of relieving stigma concerns is comparable to a monetary incentive worth more than half the daily cost of living.

The high-incentive treatment group was introduced to put a dollar value on the stigma-concern-relieving intervention. Increasing the coupon value for a test by 50 meticais (from 50 to 100 meticais) is associated with a 12.3-percentage-point increase in testing. Compared to this benchmark, the concern-relieving intervention, which induced 7.4 percentage points more tests, translates to a 30-metical (1.30 dollars by PPP) financial incentive, the size of which is over half the daily cost of living.

Conclusions and implications for future HIV policy

The campaigns fighting HIV stigma in past decades have been effective in that stigma measures have been falling, and people have become open-minded about taking in and acting on new information about stigma. Nevertheless, we show that stigmas still concern the public and have a tangible impact on health behaviour. Such impact will not be confined to testing. Still, it can challenge the entire cascade of HIV care (testing, treatment initiation, and adherence) and prevention (for example, the use of PrEP, Velloza et al. 2020).

The United Nations now aims for new targets of HIV testing, treatment, and viral suppression rates to be 95%-95%-95% (UNAIDS 2020). Demand creation (WHO 2020) is essential, and addressing stigma concerns is vital. The study makes a case for information transparency and open discussion of HIV and AIDS and their social implications. The intervention that disseminates information on low degrees of stigma can be readily scaled up at a low cost. Building on the existing achievements of anti-stigma campaigns, such a policy will push us toward achieving the last mile to a “zero stigmatisation" world.

References

Derksen, L, A Muula, and J van Oosterhout (2022), “Love in the time of HIV: How beliefs about externalities impact health behavior”, Journal of Development Economics, 159: 102993.

Granich, R M, C F Gilks, C Dye, K M De Cock, and B G Williams (2009), “Universal Voluntary HIV Testing with Immediate Antiretroviral Therapy as a Strategy for Elimination of HIV Transmission: A Mathematical Model”, The Lancet, 373(9657): 48-57.

Lowther, K, L Selman, R Harding, and I J Higginson (2014), “Experience of persistent psychological symptoms and perceived stigma among people with HIV on antiretroviral therapy (ART): a systematic review”, International Journal of Nursing Studies, 51(8): 1171-1189.

Stangl, A, L Brady, and K Fritz (2012), “Measuring HIV Stigma and Discrimination”, STRIVE Technical Brief.

Stangl, A, J Lloyd, L Brady, C Holland, and S Baral (2013), “A Systematic Review of Interventions to Reduce HIV-Related Stigma and Discrimination from 2002 to 2013: How far Have We Come?”, Journal of the International AIDS Society, 16(3S2): 18734.

MISAU, INE, and ICF (2015), Inquérito de Indicadores de Imunização, Malária e HIV/SIDA em Moçambique 2015, Ministério da Saúde (MISAU), Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE), and Com a Assistência Técnica de ICF (Maputo and Rockville).

Thornton, R (2008), “The Demand for, and Impact of, Learning HIV Status”, American Economic Review, 98(5): 1829-1836.

UNAIDS (2020), Prevailing against Pandemics by Putting People at the Centre, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (Geneva).

Velloza, J, N Khoza, F Scorgie, M Chitukuta, P Mutero, K Mutiti, N Mangxilana, L Nobula, M A Bulterys, M Atujuna, S Hosek, R Heffron, L-G Bekker, N Mgodi, M Chirenje, C Celum, S Delany-Moretlwe, and HPTN Study Group (2020), “The Influence of HIV-Related Stigma on PrEP Disclosure and Adherence among Adolescent Girls and Young Women in HPTN 082: a Qualitative Study”, Journal of the International AIDS Society, 23(3): e25463.

WHO (2020), Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Testing Services, 2019, World Health Organization (Geneva).

Yu, H (2023), “Social Stigma as a Barrier to HIV Testing: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment in Mozambique”, Journal of Development Economics, 161: 103035.