The introduction of mass public transportation systems in Lima, Peru, connected neighbourhoods, reduced commuting times, and increased access to college

There are over 500 million college students worldwide, the majority of whom are commuter students living in large urban areas. As a result, the accessibility and efficiency of city infrastructure can play a pivotal role in shaping the formation of their human capital. This challenge is especially pronounced in low- and middle-income countries, which have lower levels of transportation infrastructure than more advanced economies (Gonzales-Navarro and Zarate 2023).

Despite a large body of evidence suggesting that distance to school affects various educational outcomes (Kane and Rouse 1995, Card 2003, Agarwal and Somaini 2019), far less is known about how commuting time shapes college decisions. Improving cities' public transportation might increase access to educational opportunities in the short run, as well as improving employment prospects and welfare in the long run, as documented by Balboni et al. (2021), Tsivanidis (2023) and Zarate (2022).

A megacity with mega transportation problems

Lima, the capital of Peru and a megacity of 12 million people, had no public mass transportation systems until 2010. Lima's population is comparable to other large cities around the world, such as New York City, Paris, Xi’an, Chennai, Jakarta, Bogota, and Los Angeles. However, Lima is not nearly as dense, and commuting across the city can take up to three hours during rush hour. During the 90s, market liberation policies allowed used cars and minibuses to be imported, which became the main mode of transportation for commuters, but their poor quality and a lack of transit regulations meant that safety standards for commuters, and particularly young commuters, were low. By 2010, 57% of those involved in a traffic accident were under 25 years of age.

In July 2010, the city opened Metropolitano, a bus rapid transit line that connected the north and south of the city. The Metropolitano was the very first mass transportation public system in Peru, connecting 12 out of 44 districts. A year after the Metropolitano opened, the Peruvian president inaugurated the first line of the Metro de Lima, which was built on an elevated viaduct. This train connected the northeast side of the city with the southeast side, linking over two million people.

The introduction of these two mass public transportation systems reduced commuting times by as much as an hour and a half for connected neighbourhoods on the outskirts of the city. For thousands of commuter students residing in such neighbourhoods, the reduction on their commuting time was 17% on average. This magnitude is significant, especially when taking into account that these students typically traveled two hours back and forth to their college campuses.

The causal impact of reducing commuting time to college

To estimate the causal effects of this reduction, I created a novel dataset of college and student location, geocoding an entire decade’s worth of students' household locations. My design compares the educational choices and outcomes of cohorts in neighbourhoods exposed to new stations to the same cohorts in neighbourhoods that were exposed to planned-but-not-executed stations.

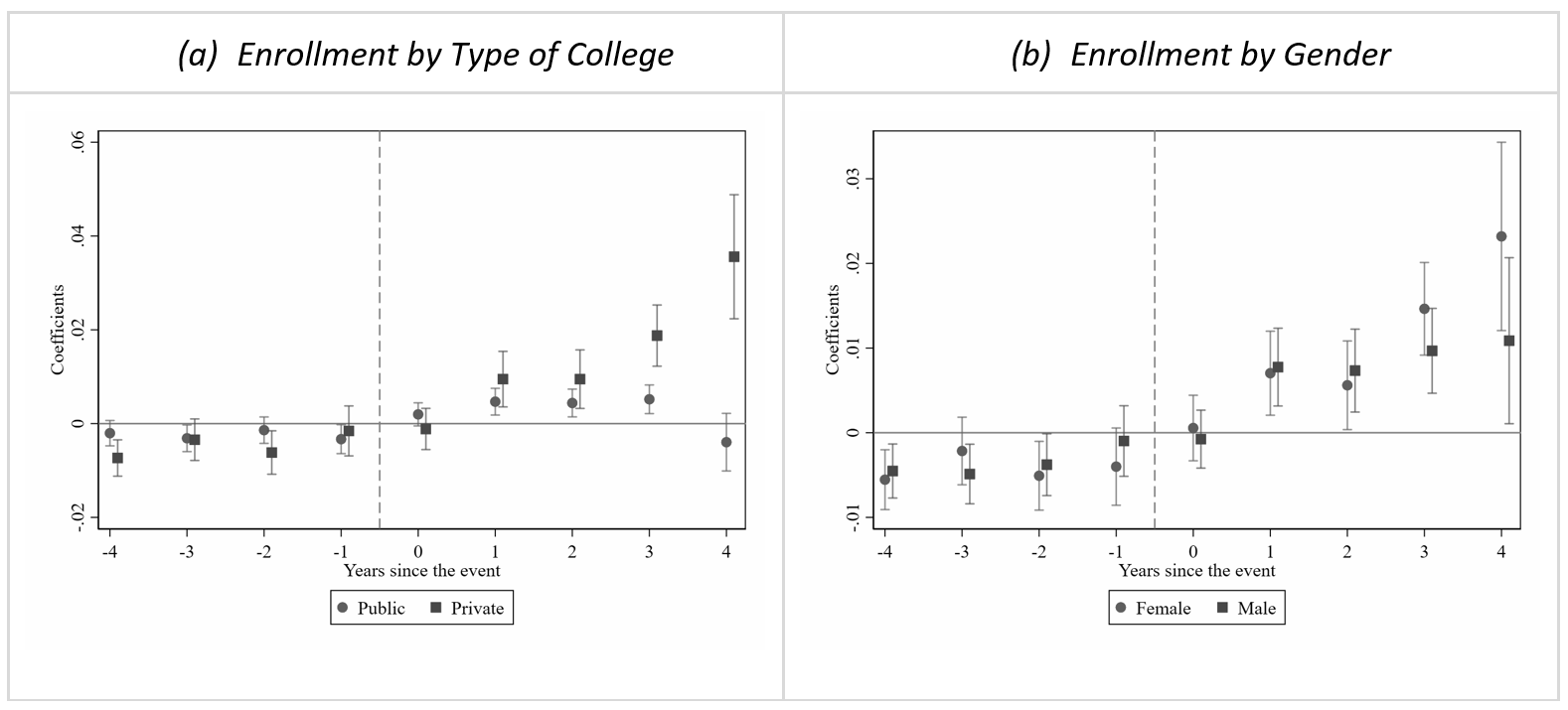

I find that neighbourhoods connected to new lines experience a one percentage point (p.p.) increase in enrollment rates, on average, relative to neighbourhoods connected to planned-but-not-executed stations. Private colleges experience higher impacts that increase over time, while public colleges show a smaller impact as seen in Figure 1, panel (a). These results reflect the Peruvian higher education landscape, in which private colleges are less selective and more able to accommodate new demand, especially those that are low-cost, while public colleges are typically more selective and oversubscribed given their tuition-free nature. Interestingly the size of these two increases for men and women are similar, suggesting no gender differences in terms of access to college (see Figure 1, panel (b)).

Figure 1: Effects of reducing commuting time on college enrollment rates

Commuting to a better college? Differences in college choice by gender

Besides increasing access to college, reducing commuting time can also affect a student's decision over which college they want to attend. In Peru, the college system lacks a centralised admissions system or a standardised admissions test, making it challenging for researchers to capture students' preferences. To address this issue, I use machine learning to identify students who were very likely to attend college (or not) in the absence of new lines. This allows me to isolate the effects on the extensive margin (a sample of students whose outside option is to not attend college) and the intensive margin (a sample of students who are attending college but might change their college of choice). Furthermore, in a context where the abundance of safety issues in transportation for women are more pronounced (Borker 2024) and building on recent evidence regarding women's demand for secure transportation, I document gender-specific disparities in college choice.

On one hand, I find that for female students who were already highly inclined to attend college (intensive margin), their choice of institution remains largely unchanged. However, female students induced to attend college by the policy (extensive margin) become more likely to attend a low-quality private college. Why? My findings suggest that the location of these colleges in the geographical centre of the city and their newfound accessibility via the new transit lines, made them more attractive for females and eased their commutes. These results align with what Borker (2021) shows in New Delhi, where female students are willing to choose lower quality colleges to avoid street harassment.

On the other hand, male students (both in the extensive and intensive margin) traded off from lower quality private colleges and became more likely to attend public ones, regardless of whether these colleges get connected or not to new lines, suggesting that men are traveling more around the city.

These results represent an overall positive for men, given that public universities yield higher wages in the laboru market than low and medium quality private colleges, at zero cost. Atop this, gender disparities are also evident in the choice of majors, with women exhibiting a greater likelihood of enrolling in non-STEM fields in low-quality institutions, while men become increasingly inclined towards STEM disciplines in public colleges.

Reducing commuting time does increase college access, but it can widen gender gaps

This study is the first to provide causal evidence on the short-term impacts of improved public city transportation on college education. However, the magnitude of these effects are smaller than those of policies which aim to directly increase college enrollment rates. For instance, initiatives like providing information (an 8 percentage point increase in FAFSA applications in Bettinger et al. (2012)), early commitment to free tuition (a 15 percentage point increase for high-achieving low-income students in a flagship university in Dynarski et al. (2021)), or scholarships (10 percentage point increase in Colombia’s Ser Pilo Paga programme in Londõno Velez et al. (2023)) have shown more substantial effects. Nevertheless, the results shed a light on the importance that commuting time can have on marginal students.

In a context where low-quality private colleges offer considerably lower wage returns in the labour market and where the gender wage gaps are pronounced, similar to many countries in the developing world, it is important to reconsider which colleges and which students benefit the most from these new systems. An increased proportion of women enrolling in lower-wage return colleges relative to men only exacerbates this divide. When designing new city transportation infrastructure, it is important to recognise how it can shape educational prospects for both men and women, and subsequently change their labour market trajectories. Moreover, the results of this paper also suggest the need to consider gender-specific travel preferences in designing transportation systems for maximum inclusivity and accessibility.

References

Agarwal, N and P Somaini (2020), "Revealed Preference Analysis of School Choice Models", Annual Review of Economics, Volume 12.

Balboni, C, G Bryan, M Morten, and B Siddiqi (2020), "Transportation, Gentrification, and Urban Mobility: The Inequality Effects of Place-Based Policies", Working Paper.

Bettinger, E, B Terry Long, P Oreopoulos, and L Sanbonmatsu (2012), "The Role of Application Assistance and Information in College Decisions: Results from the H&R Block Fafsa Experiment", Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(3) 1205–1242.

Borker, G (2021), "Safety First: Perceived Risk of Street Harassment and Educational Choices of Women", Policy Research Working Paper No. 9731, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Borker, G (2024), "Understanding the constraints to women’s use of urban public transport in developing countries", World Development, 180.

Card, D (1993), "Using geographic variation in college proximity to estimate the return to schooling", National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Dynarski, S, CJ Libassi, K Michelmore, and S Owen (2021), "Closing the Gap: The Effect of Reducing Complexity and Uncertainty in College Pricing on the Choices of Low-Income Students", American Economic Review, 111(6): 1721-56.

Gonzalez-Navarro, M, R David Zarate, R Jedwab, N Tsivanidis (2023), "Land Transport Infrastructure", VoxDevLit, 9(1).

Kane, T and C Rouse (1995), "Labor-Market Returns to Two- and Four-Year College", American Economic Review, 85(3): 600–614.

Londoño-Vélez, J, C Rodriguez, F Sanchez, and L Álvarez-Arango (2023), "Financial Aid and Social Mobility: Evidence from Colombia's Ser Pilo Paga", NBER Working Papers 31737.

Tsivanidis, N (2023), "Evaluating the Impact of Urban Transit Infrastructure: Evidence from Bogota’s TransMilenio", Working Paper.

Zarate, R (2022), "Spatial Misallocation, Informality, and Transit Improvements: Evidence from Mexico City", World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9990.