Variation in social structure shapes the formation of financial ties and the spillover effects of public policy in East Africa

Informal income transfers are pervasive in developing countries. They affect many aspects of daily life and help prevent temporary income shocks from leading to major hardship. Moreover, the pattern and scale of these informal interactions shape the aggregate impacts of public policy, as individuals redistribute resources within their economic and social networks.

In economic analysis, families or villages are typically assumed to be the main groups in which these informal interactions take place, and individuals form financial ties in order to smooth consumption in the face of fluctuating economic conditions (e.g. Townsend 1994 1995). A long tradition of research in anthropology, however, has documented that there are vast and persistent differences in the pattern of social and economic exchange across cultures (e.g. Benedict 1934).

According to these accounts, seemingly universal social groupings like the family vary widely in relevance, and patterns of exchange and allegiance differ markedly across societies. By largely ignoring differences in social organisation and how they vary across societies, economists may be missing a key determinant of the pattern and strength of financial ties, as well as a useful tool for understanding the distributional consequences of development policy.

In a recent paper, we directly investigate the extent to which long-standing features of social organisation shape present-day economic interactions and the spillover effects of policy (Moscona and Seck 2023). The focus of our analysis is the stark distinction between societies with and without “age sets,” described by Lowie (2021) as the “most important example of an alternative to kinship-based organisation.” In some societies, perhaps most familiar to those in the West, the extended family (kin group) is the main social group and the one in which social and financial ties are strongest. In societies with age sets, however, the primary social unit is often a group of individuals who are of similar age and initiated into adulthood at the same time (the “age set”); the strongest feelings of obligation are between individuals of the same cohort, who pass through each phase of life as a group.

Age set organisation

Age sets have been thoroughly studied by anthropologists, whose accounts suggest that age set organisation leads to stronger within-cohort economic ties and weaker within-family or inter-generational economic ties (e.g. Radcliffe-Brown 1929). For example, Eistenstadt (1954) writes that “relations between age mates [involve] general and permanent obligations of cooperation, solidarity, and help.” Describing contemporary Maasai society in Kenya, Spencer (2014) notes that “it is toward age mates that men look to for support rather than brothers or close patrilineal kin.” These studies suggest that the pattern of social and economic ties could be substantially different in societies with and without age sets. By our own estimates, over 200 million people today live in ethnic groups in which age sets are the traditional form of social organisation; yet the impact of age-based organisation on economic activity remains largely unknown.

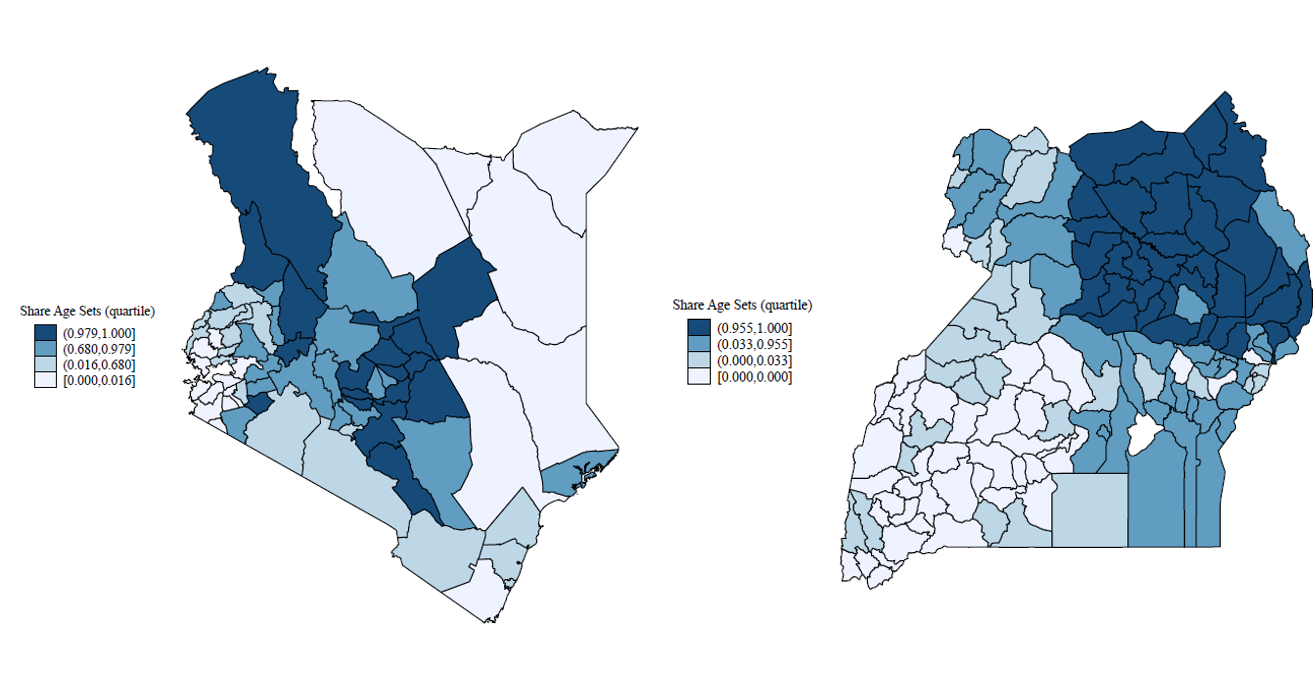

Our analysis focuses on Kenya and Uganda, where societies both with and without age sets are common. Using a range of ethnographic sources, we first determine whether age sets are a primary form of social organisation for all ethnic groups living in Kenya and Uganda. Figure 1a displays a map of Kenya and Figure 1b displays a map of Uganda, in which each county or district is colour-coded based on the share of the population that, according to our database, is a member of an age set society. To construct this map, we linked our group-level data with self-reported ethnic affiliation in the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). Members of age set societies make up 72% of the surveyed households in Kenya and 29% of the households in Uganda.

Figure 1: Age set societies in Kenya and Uganda

Notes: These maps display country boundaries in Kenya (1a) and district boundaries in Uganda (1b). Regions are color-coded based on the share of Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) households in each district that are members of age set societies. Districts are divided into four quartiles based on the share of the population comprised of members of age set societies, with darker colors corresponding to higher shares. The data are from the most recent geo-coded wave of the DHS in each country.

Experimental evidence: social structure affects financial ties

In the first part of our analysis, we study a cash transfer programme in Kenya in order to directly investigate how exogenous income changes are re-distributed in societies that have age sets, compared to societies that do not. This makes it possible to directly test the hypothesis that differences in social organisation affect the pattern of financial ties and transactions, even zooming in on groups that reside in close proximity. In particular, we exploit a randomised evaluation of the Hunger Safety Net Program (HSNP), which took place across 48 sub-locations in Northern Kenya. In both treatment and control sub-locations, some households were selected to receive the transfer; however, the transfers were only actually disbursed in the randomly-selected treatment sub-locations.

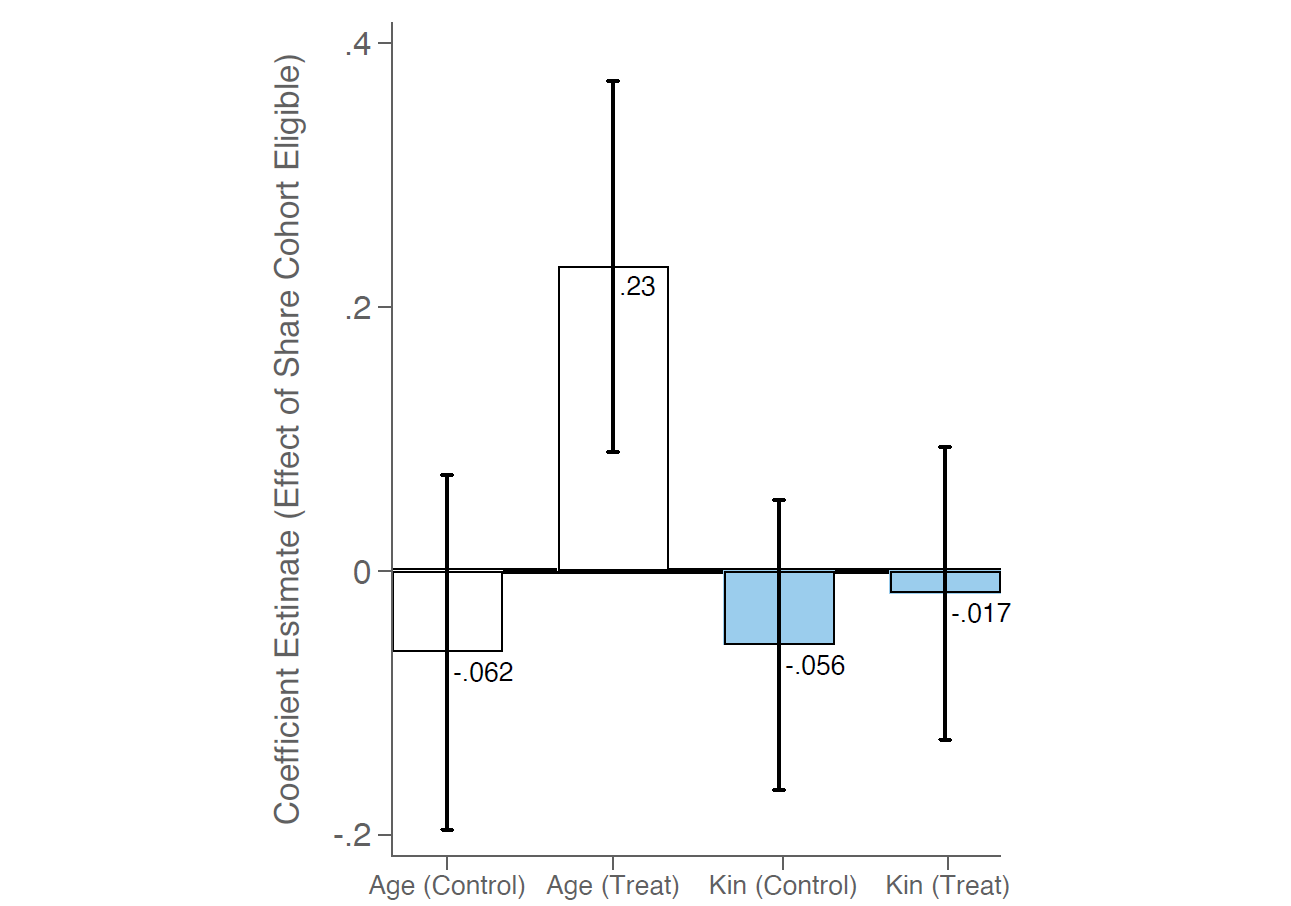

To investigate within-cohort spillovers, we estimate how household consumption changes when a cohort member of the household head receives an income transfer. The results are summarised in Figure 2. All bars report the effect of a household head’s cohort member being selected to receive a cash transfer on household consumption; however, each bar focuses on a different sub-sample. The first and third bars focus on members of age-based and kin-based societies respectively, in the control group. Since in both cases the transfers were never actually given out, both bars are statistically indistinguishable from zero. The second and fourth bars, however, focus on members of age-based and kin-based societies in the treatment group. Here, there are clear within-cohort spillover effects of the transfer in age-based societies, but these spillover effects are absent in kin-based societies. In age set societies, cohort-level financial ties are strong and these ties seem much less important in kin-based societies.

Figure 2: Spillover effects of cash transfers in age-based vs kin-based societies

Notes: Each bar reports the coefficient estimate of the relationship between a main provider’s household consumption spending and the share of his cohort eligible for the cash transfer. The regression is estimated on the sub-sample noted at the bottom. From left, these are: age set societies in control sub-locations, age set societies in treatment sub-locations, non-age set societies in control sub-locations, non-age set societies in treatment sub-locations. Interviewer and targeting code by ethnicity fixed effects are included in all specifications. 95% confidence intervals are reported.

We next ask whether the strong within-cohort ties in age-based societies function in addition to or instead of within-family ties. To do this, we use self-reported data on sub-clan membership as a proxy for the extended family. We find the exact opposite pattern as the one presented in Figure 2: there are strong within-family spillovers in kin-based societies but these spillovers are entirely absent in age set societies. As an additional test, we zoom in on one arm of the cash transfer experiment which was meant to simulate a pension programme. In kin-based societies, the pension programme led to greater investment in children, as proxied by spending on education. However, we find no evidence of this effect in age-based societies. Together, we interpret these results to mean that age set societies have weaker ties within families and across generations. Differences in social organisation are associated with a completely different economic network structure.

Policy analysis: Social structure affects distributional consequences

In the second part of our analysis, we investigate the implications of these differences for the distributional consequences of country-wide public policy. We study the roll out of Uganda’s national pension programme (the “Senior Citizen Grant” programme). We exploit the fact that the programme was first piloted in fifteen districts, making it possible to compare pension-eligible households in pilot vs. non-pilot districts. Our main question is how the pension programme affected intergenerational investment in children, separately in households that are members of age-based vs. kin-based groups. To measure investment in children, we compile a range of data on child health outcomes from Uganda’s DHS.

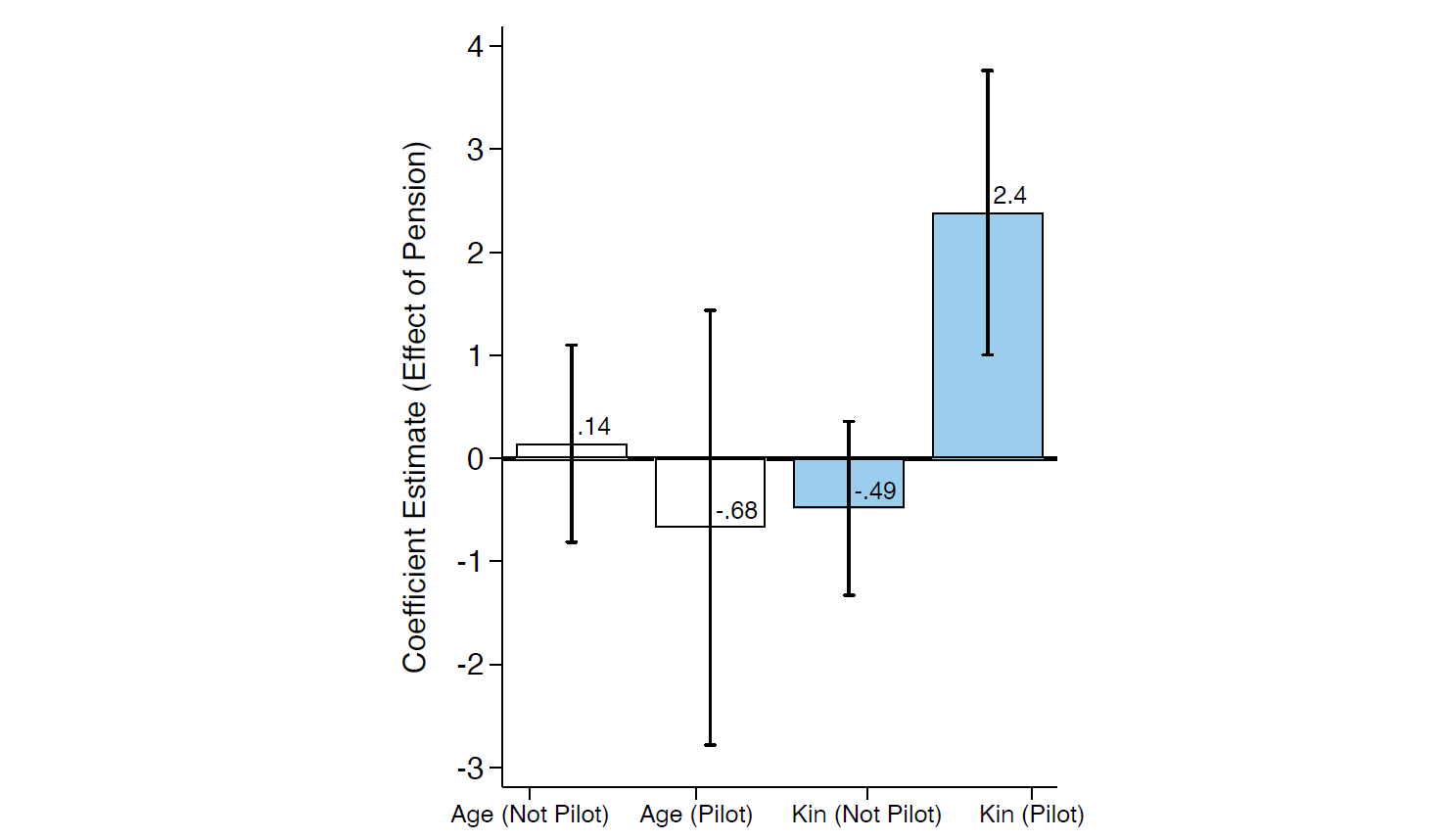

The main results are summarised in Figure 3, which follows a similar structure to Figure 2. The unit of observation is a child in the DHS data and the outcome variable is weight-for-height, a standard proxy for nutritional well-being. The first and third columns report the effect of pension eligibility for households that are members of age-based vs. kin-based ethnicities in non-pilot districts. Intuitively, both bars are indistinguishable from zero since these households are in districts where the pension had not been introduced. The second and fourth columns, however, show the effect of pension eligibility in age-based and kin-based households in pilot districts. Here, we see large effects of the pension programme on child nutrition in kin-based societies; this effect is absent in age-based societies.

Figure 3: Spillover effects of pension programme in age-based vs kin-based societies

Notes: Each bar reports the coefficient estimate of the relationship between a child’s weight-for-height percentile and household-level pension eligibility exposure. The regression is estimated on the sub-sample noted at the bottom. From left, these are: age set societies in non-pilot districts, age set societies in pilot districts, non-age set societies in non-pilot districts, non-age set societies in pilot districts. District-by-ethnicity and interview month fixed effects are included in all specifications. 95% confidence intervals are reported.

The effects are large: an additional year of the pension programme increases child weight by 0.15 standard deviations and reduces the probability of malnourishment by 5.5% in kin based societies, but has no effect in age-based societies. We find similar effects for other measures of child nutrition and for school attendance. These findings show that differences in local social organisation can dramatically alter the consequences of major public policy. While the primary beneficiaries of any pension programmes are the elderly, Uganda’s Ministry of Gender, Labour, and Social Development also expected the programme to help children, noting on its website that the pension grants will benefit children “as older people tend to invest a portion of their grant money in meeting their grandchildren’s nutritional, health, education needs.” Our results suggest that these broader consequences of policy, however, are mediated by social structure.

Zooming out: social organisation, inequality, and vulnerability

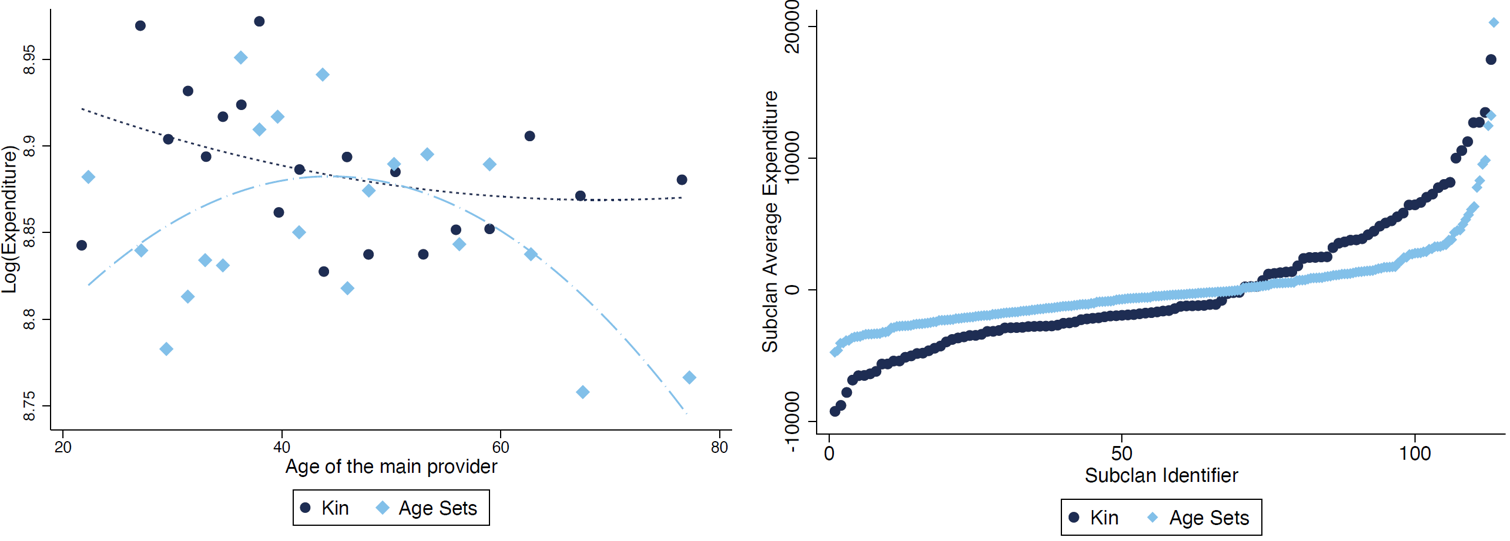

A final question is how social organisation shapes broader patterns of inequality and vulnerability in society. Returning to consumption data from Kenya’s HSNP, Figure 4a displays the distribution of consumption by age, separately in age-based and kin-based societies; and Figure 4b displays the distribution of consumption by sub-clan, in age-based and kin-based societies. Two clear patterns emerge. While consumption over the lifecycle is relatively flat in kin-based societies, in age-based societies the young and old consume systematically less (Figure 4a). This greater cross-cohort inequality could be driven by the fact that the young and old have fewer high earners in their network in age-based societies and are left more vulnerable as a result. In kin-based societies, the young can turn to older family members and the elderly can turn to younger family members. At the same time, while consumption differences across sub-clans are relatively limited in age-based societies, perhaps because age sets cut across clan lines, there is substantial cross-clan inequality in kin-based societies (Figure 4b).

Figure 4: Social organisation and inequality

Notes: Figure 4a displays binned scatter plots of log of household consumption expenditure (y-axis) vs. the age of the main provider (x-axis), separately for members of age set societies (light diamonds) and kin-based societies (dark circles). Quadratic fit curves are also displayed. We partial out sub-location fixed effects and the number of household members. Figure 4b displays scatter plot of consumption expenditure (y-axis) vs. sub-clan identifiers (x-axis) plotted separately for members of age set societies (light diamonds) and kin-based societies (dark circles). Sub-clans are ordered by their average consumption spending, which is normalised by the mean consumption spending for each series.

These findings suggest that social organisation may shape not only the consequences of income and policy shocks but also baseline patterns of poverty and vulnerability. Age set organisation is one example of the vast differences in social structure that exist around the world; others include secret societies, cults and religious groups, gender-based groups, military associations, and clan super-sets that link individuals across broad geographic expanses. Better data and a deeper understanding of these different forms of social organisation could be invaluable resources for predicting and analysing financial networks, the consequences of public policy, and patterns of vulnerability. This all strikes us as an exciting area for future work.

References

Benedict, R (1934), Patterns of culture, Boston; New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Eisenstadt, S N, (1954) “African age groups: a comparative study,” Africa, 24(2): 100.

Lowie, R H (1921), Primitive Society, New York: Liveright.

Moscona, J and A A Seck (2023), “Age Set vs. Kin: Culture and Financial Ties in East Africa,” Working paper. Available here: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3956141.

Radcliffe-Brown, A R (1929), “Age organization terminology,” Man, 29(21).

Spencer, P (2014), Youth and Experiences of Ageing Among Maa: Models of Society Evoked by the Maasai, Samburu, and Chamus of Kenya, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

Townsend, R M (1994), “Risk and insurance in village India,” Econometrica, pp. 539–591.

Townsend, R M (1995), “Consumption insurance: An evaluation of risk-bearing systems in low-income economies,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(3): 83–102.