Higher media reporting of sexual assaults reduces women’s likelihood of working outside their homes in urban India

Incidents of sexual assault and rape in developing countries often receive extensive media coverage. Recent notable cases include the December 2012 gang rape and murder case in Delhi and, more recently, the September 2020 gang rape in the south eastern Noakhali district of Bangladesh. Such media reporting can inadvertently deter working-age women from going out of their homes to work by emphasising the violence that women and girls risk facing.

In India, an array of empirical research indicates that women’s safety concerns outside the home are likely to play a key role in their economic activity. Muralidharan and Prakash (2017) find that providing girls in the Indian state of Bihar with a bicycle improved secondary school enrolment by making it safer and quicker for girls to travel to school. Borker (2018) finds that women are willing to choose a lower quality college at the University of Delhi for a travel route that they perceive to be safer. Chakraborty et al. (2018) find that in urban neighbourhoods where self-reported levels of sexual harassment against women are high, women are far less likely to seek outside employment.

Violence in the media and women’s fear of public safety

In a recent paper, I examine media’s influence of reporting violence on women’s likelihood of working using data from urban India (Siddique 2020). I use Indian labour market data between 2009 and 2012 combined with a geographically referenced data source on media reports of physical and sexual assaults that occurred in Indian districts over time. Using the combined data, I investigate the effect of media-reported violence in the local area (Indian district) in the past quarter on a resident woman’s decision to work outside her home today.

I find that a one standard deviation increase in sexual assault reports per 1000 people within the local area of a woman leads to a reduction in the probability that she works outside her home by 5.5%. By contrast, physical assault reports have no effect on whether women work outside the home; neither do sexual assault reports on whether men work outside the home.

The negative effect of sexual assault media reports on female labour supply remains even after including additional controls for exogenous labour demand shocks. These controls help me to rule out alternative explanations of my findings, such as how a negative labour demand shock could potentially cause increasing violence against women by way of reduced female employment as well as female bargaining power within households. In additional analyses, I control for the underlying level of crimes against women (including rapes, assaults and insults) reported to the police in a district in the past year. I continue to find a negative and statistically significant effect of sexual assault media reports on female labour supply whilst holding constant the underlying level of crimes against women reported to the police.

For how long do women stay home?

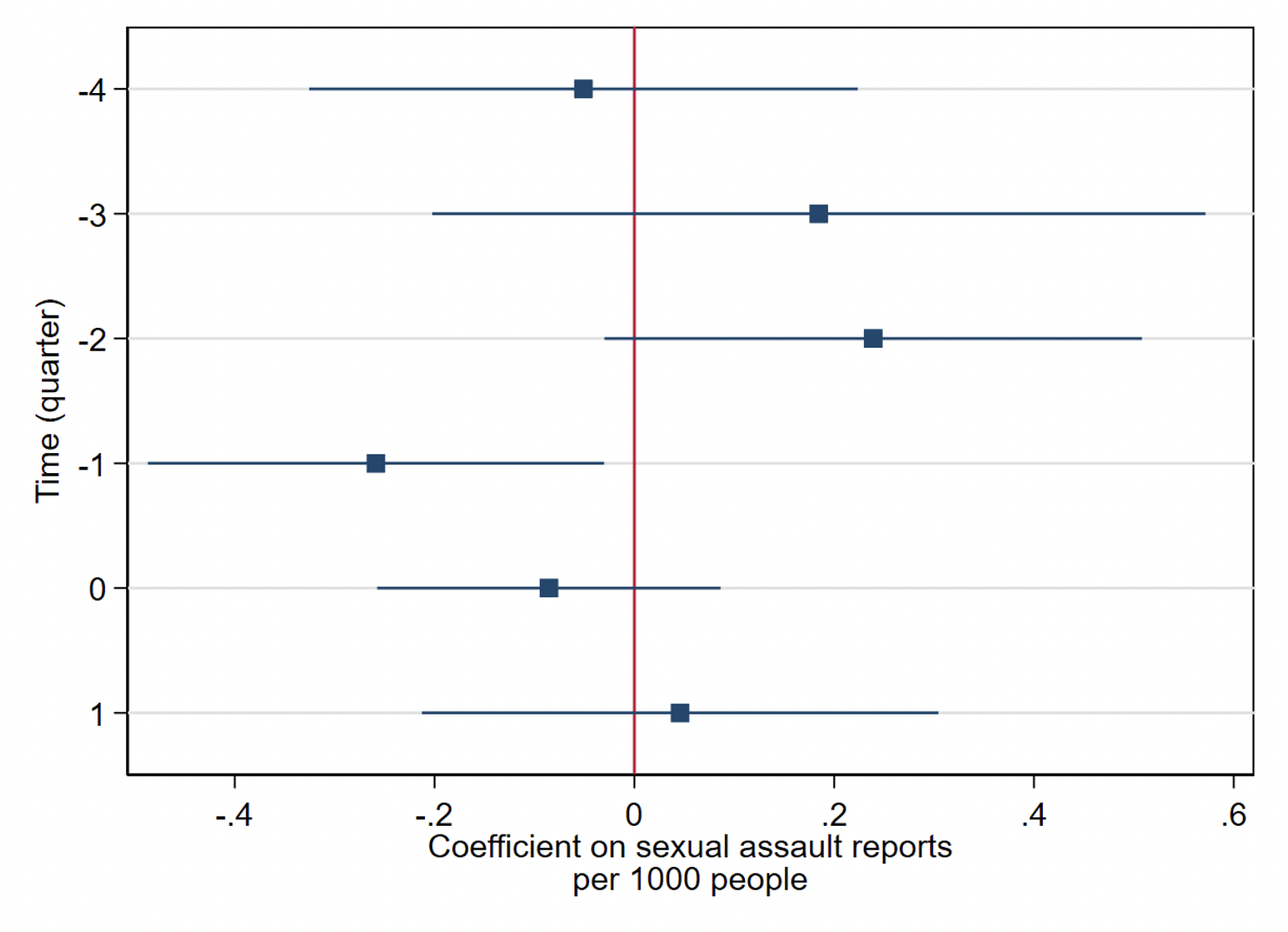

The results also uncover suggestive evidence that this effect is short-lived, with female labour supply increasing to catch-up following an initial decline. As seen in Figure 1, the coefficient on the one-period (quarter) lag of sexual assault media reports is negative and statistically significant while the coefficient on the two-period lag is positive, but just misses statistical significance at the 5% level. The coefficient on the one-period lead of sexual assault media reports is close to zero, which serves as a useful placebo check on my results. I carry out a further placebo experiment using additional Indian labour market data from between 2005 and 2008 which also confirms the findings.

Figure 1 Coefficient plot showing the effect of sexual assault media reports on female labour supply

In addition, as sexual assault victims are more likely to be younger women, age may be an important determinant. In 2017, about 30% of police registered rape victims in India were women younger than 18, while 50% were between 18 and 30 years old. Upon further analysis, I find that the negative effect of media-reported violence on female labour supply is concentrated among young women who are between 18 and 25 years old. Among these women, the effect is more than twice as large as the effect estimated for all working-age women, while the effect is smaller (although still negative) and statistically insignificant for older women alone.

Policy implications

The results of this research highlight the importance of addressing safety concerns of women in India, particularly young women. Longer-term interventions could involve strengthening policing and legal frameworks that protects women from sexual assaults. Shorter-term interventions could involve provision of special transport facilities for women. Aguilar et al. (forthcoming) examine a program that reserves subway cars for women in Mexico City and find that this reduces sexual harassment towards women. In Rio de Janeiro, Kondylis et al. (2018) find that riding in women-reserved safe spaces reduces harassment against women. However, both studies also find negative effects – in Mexico City there is an increase in non-sexual aggression incidents among men, while in Rio de Janeiro there is stigmatisation of women who ride female-only cars. Hence, policy prescriptions to address women’s safety concerns need to be made with care to achieve the desired impact.

Editors’ note: A shorter version of this column first appeared on the University of Bristol School of Economics blog.

References

Aguilar, A, E Gutierrez and P S Villagran (forthcoming), “Benefits and unintended consequences of gender segregation in public transportation: Evidence from Mexico City’s subway system”, forthcoming in Economic Development and Cultural Change.

Borker, G (2018), “Safety first: Perceived risk of street harassment and educational choices of women”, Job Market Paper.

Chakraborty, T, A Mukherjee, S R Rachapalli and S Saha (2018), “Stigma of sexual violence and women’s decision to work”, World Development 103: 226-238.

Kondylis, F, A Legovini, K Vyborny, A Zwager and L Andrade, (2018), “Demand for safe spaces: Avoiding harassment and stigma”, Unpublished Manuscript.

Muralidharan, K and N Prakash (2017), “Cycling to school: Increasing secondary school enrolment for girls in India”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9(3): 321-350.

Siddique, Z (2020), “Media reported violence and female labor supply”, accepted for publication in Economic Development and Cultural Change.