Refugee inflows from Syria to Turkey led to the displacement of women in the labour force, but also reduced the risk of intimate partner violence

Intimate partner violence is a widespread social problem that is associated with poor health and economic outcomes for women and their children. On average, 30% of women aged 15 or older have experienced physical or sexual violence from their partners during their lifetimes across the world (Devries et al. 2013). The costs of intimate partner violence are staggering. In the United States alone, the lifetime economic costs of intimate partner violence amount to $3.6 trillion, with $1.3 trillion attributed to productivity losses (Peterson et al. 2018). Despite such high costs, there is no consensus on the underlying causes of intimate partner violence.

While women’s economic empowerment has long been touted as an important tool in reducing risk of intimate partner violence, the relationship between female economic empowerment and domestic violence can be complicated. On one hand, an increase in resources available to women may increase their bargaining power within the household, reducing their exposure to violence. On the other hand, a rise in female resources through, for example, conditional cash transfers may strengthen men’s incentives to use violence as an instrument for extracting resources from women. In fact, a growing body of work has shown that an increase in resources available to women may trigger backlash effects from men (Bloch and Rao 2002, Bobonis et al. 2013, Erten and Keskin 2018).

The differential inflow of Syrian refugees across Turkey

In our recent research, we focus on the effect of a particular empowerment mechanism – female employment – on the risk of intimate partner violence in Turkey (Erten and Keskin 2020). We focus on a developing country, Turkey, which has a high rate of intimate partner violence (34% of women experience physical or sexual violence from their partners) and low levels of women’s empowerment. In our study, we use the differential inflow of Syrian refugees across Turkish provinces after the Syrian civil war in March 2011 as an exogenous shock to female employment. Our findings reveal that Syrian refugee inflows led to a decline in female employment with no significant impact on male employment. Our findings also show a significant fall in intimate partner violence in the provinces that received a higher share of Syrian refugees. Moreover, declines in both female employment and intimate partner violence were concentrated amongst women with lower levels of education. Examining alternative channels, we find no significant impacts on partner characteristics, gender attitudes, cohabitation patterns, or the division of labour within the household.

Decline in female employment driven by Syrian refugee inflows to Turkey

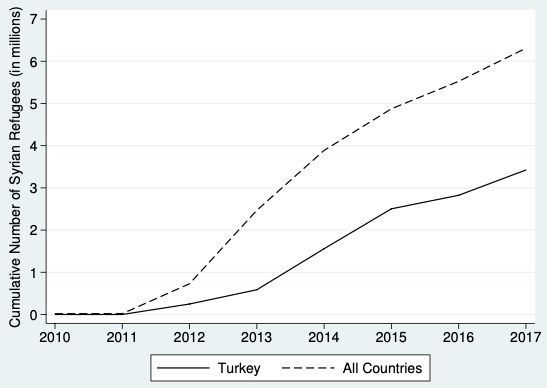

In March 2011, the violent response of the Bashar Al-Assad regime to peaceful civil protests triggered one of the most destructive civil wars in Syria. The war rapidly spread across several regions of Syria, resulting in 12.5 million displaced individuals by 2017. Out of 6.3 million that migrated to neighbouring countries, 3.4 million refugees settled in Turkey as the primary destination of settlement (followed by Lebanon and Jordan). Figure 1 illustrates that the total number of refugees that fled to Turkey rose from 8,000 in 2011 to 1.6 million in 2014, a 200-fold increase in merely three years.

Figure 1 Number of Syrian refugee inflows

Note: The data come from the official number of Syrian refugees reported by the UNHCR online database.

As Figure 2 shows, Syrian refugees originated predominantly from northwest Syria, where the conflict began and spread. The highest shares of refugee outflows belong to the governorates of Aleppo (36%), Idleb (21%), Ar-Raqqa (11%), Lattakia (9%), and Hamah (8%). About 80% of the refugees reported that they chose to migrate to Turkey primarily due to lower transportation costs (Directorate General of Migration Management of Turkey 2013).

Figure 2 Origin of Syrian refugees (%)

Note: The data come from the Directorate General of Migration Management in Turkey.

The Turkish government enacted a Temporary Protection Regime as a response to refugee inflows in October 2011. Under this policy, the Syrian immigrants were assured no forced return and were provided access to education, health services, and social assistance. Nevertheless, the refugees were not provided any formal work authorisation until January 2016, as a result of which most of them were initially employed in the informal sector .

Figure 3 provides the geographical distribution of Syrian refugees in Turkey using the proportion of refugee inflows in province population in 2014. The provinces with the highest refugee shares are Hatay, Kilis, and Sanliurfa, which are all located on the Turkish-Syrian border, while provinces away from the border received fewer refugees. In an average province, the population share of refugees was 2% in 2014.

Figure 3 Share of Syrian refugees in Turkish population, 2014 (%)

Note: The data come from the Directorate General of Migration Management in Turkey.

While the Syrian civil war and the ensuing refugee crisis were completely exogenous for our purposes, it is possible that refugees were not located at random. Following Del Carpio and Wagner (2015), we use a weighted average of the travel distance between 13 origin governorates in Syria and 81 Turkish provinces (1,053 origin-destination pairs) as an instrument to predict the location choice of the refugees. Our findings on labour market outcomes indicate that Syrian refugees primarily displaced female workers, with stronger effects in the private sector driven by displacement within agricultural and service sector employment. In contrast, we find no evidence that Syrian refugee inflows significantly influenced male labour market outcomes. These findings are consistent with descriptive studies which documented that Syrian refugees were more likely to accept low wages and inferior working conditions in the informal sector. Since Turkish women were much more likely to be employed within the informal sector prior to the arrival of refugees, the displacement effects were stronger for women.

Declines in female employment reduced the risk of experiencing intimate partner violence

Our results also indicate that the Syrian refugee inflows led to a reduction in women’s experience of physical, sexual, and psychological violence from their husbands. Given that the Syrian refugees had relatively low levels of education and lacked work permits in the earlier years, the displacement effects were concentrated amongst less-educated Turkish women who were mainly employed in the informal sectors before the refugee influx. As a result, the declines in intimate partner violence were also disproportionately observed for less-educated women who had completed middle school or less.

Exploring alternative channels through which Syrian refugee inflows could affect domestic violence, we find no evidence for other potential explanations, including changes in gender attitudes, marriage market outcomes, co-residence with parents, or the division of labour within the household.

Findings consistent with instrumental theories of violence

Taken together, our findings on labour market and intimate partner violence outcomes are consistent with instrumental theories of violence, whereby a decline in a woman’s earnings opportunity reduces the incentives of her male partners to use violence as a means of rent extraction. The Syrian refugee inflows induced a disproportionate reduction in women’s employment and income, reducing men’s incentives to use violence as a means of extracting resources from women. As a consequence, women experienced a decline in their risk of facing intimate partner violence.

References

Bloch, F and V Rao (2002), “Terror as a bargaining instrument: A case study of dowry violence in rural India”, American Economic Review 92(4): 1029–1043.

Bobonis, G J, M Gonzalez-Brenes and R Castro (2013), “Public transfers and domestic violence: The roles of private information and spousal control”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 5(1): 179–205.

Devries, K M, J YT Mak, C Garcia-Moreno, M Petzold, J C Child, G Falder, S Lim, L J Bacchus, R E Engell, L Rosenfeld and C Pallitto (2013), “The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women”, Science 340(6140): 1527–1528.

Directorate General of Migration Management of Turkey, “Syrian Refugees in Turkey, 2013: Field Survey Results,” Technical Report 2013.

Erten, B and P Keskin (2018), “For better or for worse? Education and the prevalence of domestic violence in Turkey”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10(1): 64–105.

Erten, B and P Keskin (2020), “Female employment and intimate partner violence: Evidence from Syrian refugee inflows to Turkey”, Working Paper.

Peterson, C, M C Kearns, W LiKamWa McIntosh, L F Estefan, C Nicolaidis, K E McCollister, A Gordon and C Florence (2018), “Life-time economic burden of intimate partner violence among US adults”, American Journal of Preventive Medicine 55(4): 433–444