Action plans are a cost-effective way to improve job search outcomes for unemployed youth

Job search is a largely self-regulated process, subject to behavioural biases that lead to sub-optimal search and employment outcomes. Existing studies show that search intensity depends on job seekers' biases in beliefs about returns to search efforts (Spinnewijn 2015), on their level of impatience (DellaVigna and Paserman 2005), on their locus of control (Caliendo et al. 2015, McGee and McGee 2016), as well as on their self-confidence and willpower (Falk et al. 2006). This is particularly important given that a rising number of young people globally are not enrolled in education, employed, or searching for work.

Evidence suggests that in the presence of high and persistent unemployment, South African youth are becoming increasingly discouraged in their job search. In our sample of youth who are motivated enough to come to a labour centre, we find that job seekers spend an average of 11 hours per week searching for jobs, and only submit about four job applications per month. They want to intensify their job search, and set aside the time and intend to search but their behaviour falls short of their intentions. The dilemma arises in ensuring follow-through on their goals.

Behaviourally informed strategies like action planning can help job seekers follow through on their job search intentions and increase their search efforts. Evidence shows that planning and scheduling tasks help people follow through on a variety of behaviours, ranging from voting to exercising. Rogers et al. (2015) and Hagger and Luszczynska (2014) provide recent reviews of this literature. We extend this research to the novel domain of job search (Abel, Burger, Carranza and Piraino 2019).

Designing, implementing and evaluating the effect of action planning

Our action planning intervention draws on insights from the psychology literature regarding the use of plan-making prompts to bridge the gap between job search intention and behaviour.

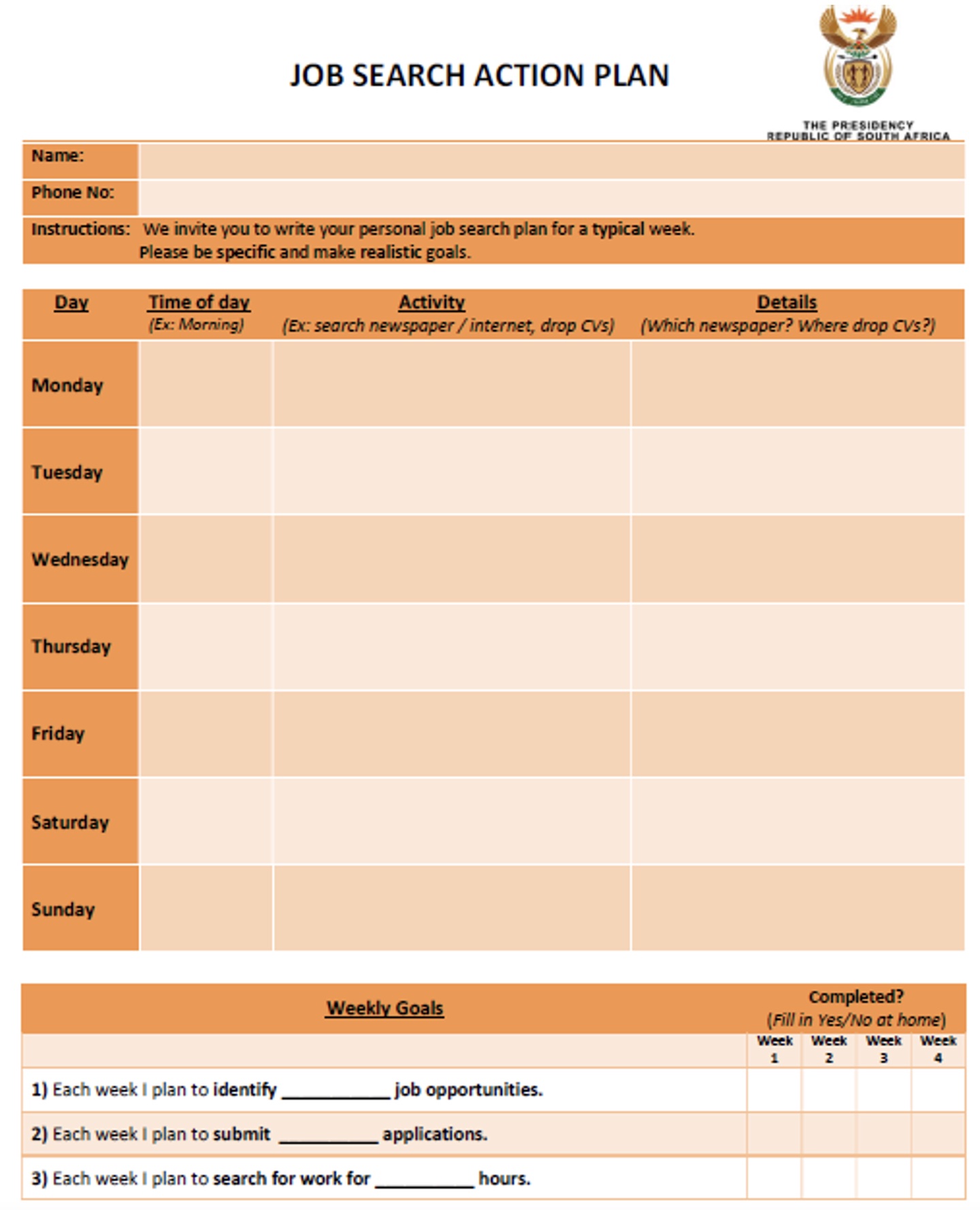

Figure 1 shows the action plan template we designed. In the template, we first ask job seekers to fill a weekly chart with detailed day-by-day entries for whether, how, and where they will search. We then ask them to organise their entries into weekly goals for the number of hours to search and the number of applications to submit.

Figure 1 Action plan template

Note: The template provides space for daily entries which can be condensed into weekly goals for hours and number of applications to submit as part of job search.

We tested the effect of plan-making on job search behaviour and employment in a field experiment with a sample of 1,100 unemployed South African youth who participated in the standard 90-minute career-counselling workshops conducted by the Department of Labour. During the workshop, career counsellors cover topics such as job search strategies, CV creation, interview techniques, and access to information and resources for job search. Additional to this standard workshop, we prompted job seekers to complete an action plan template. We then asked them how their entries add up to weekly goals, how many hours they plan to search, and how many applications they plan to submit.

Action planning led to improved employment outcomes

We constructed a measure of the intention-behaviour gap by comparing respondents' search intentions with reported behaviour at baseline. We found the presence of an intention-behaviour gap in terms of job applications submitted but did not find this gap in hours spent on job search activities. Respondents aimed to submit 6.6 more applications per week than they actually did and planned to spend 3.4 hours less on job search (but this is centred around zero).

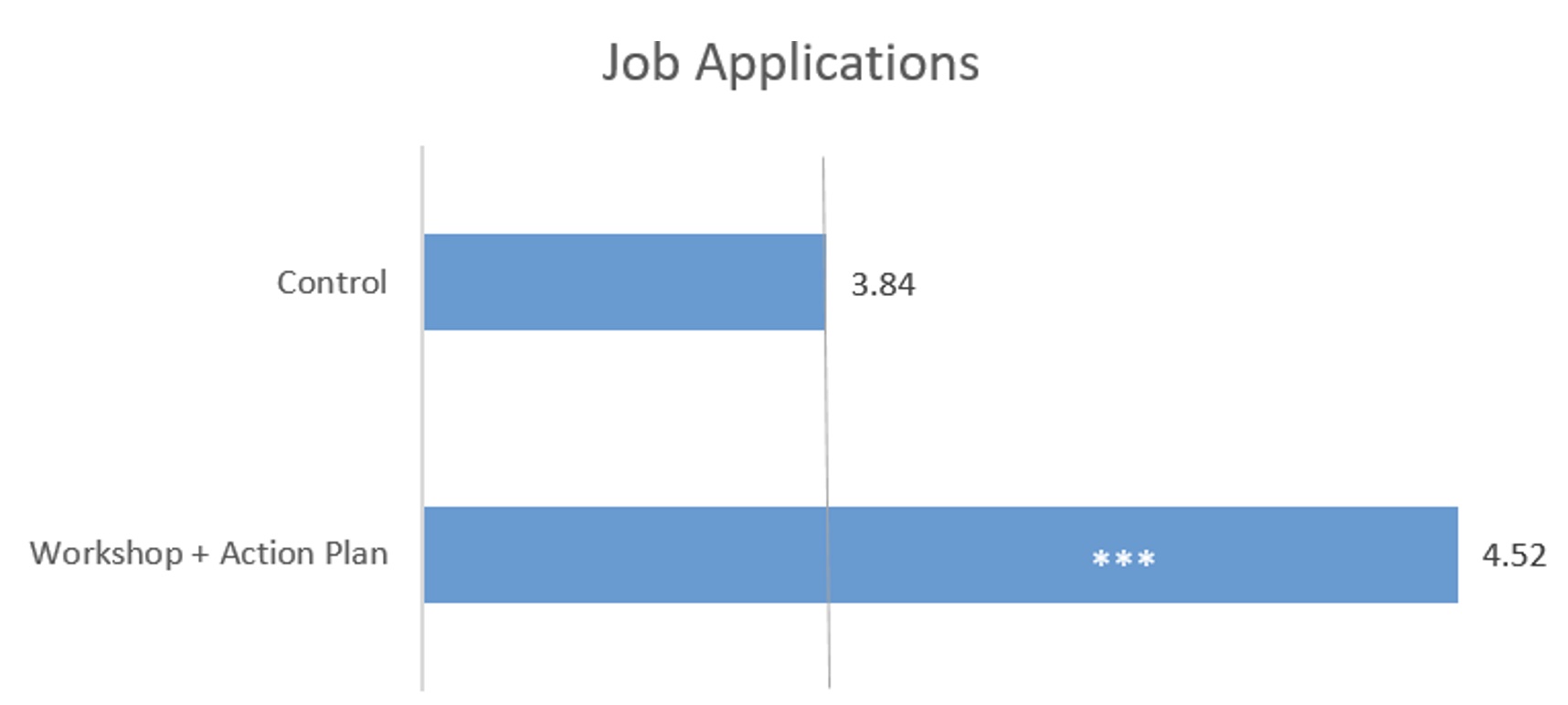

Five to twelve weeks after the intervention, we found increases in job search intensity in accordance with the intention-behaviour gap. We found that participants who completed a detailed job search plan increased the number of job applications submitted, but not the number of hours spent searching. At follow up, the action plan group submitted 0.7 additional applications – 15% more than the group receiving standard job counselling, and 18% more than the pure control group. While this is a sizeable increase relative to the low number of applications at baseline, it only partially closes the intention-behaviour gap.

Figure 2 Outcomes of action plan versus control group

Note: The figure shows the treatment effect of using action plans during job search. Those who completed action plans submitted 15% more applications than those who received only job counselling, and 18% more than those who did not receive action plans or counselling.

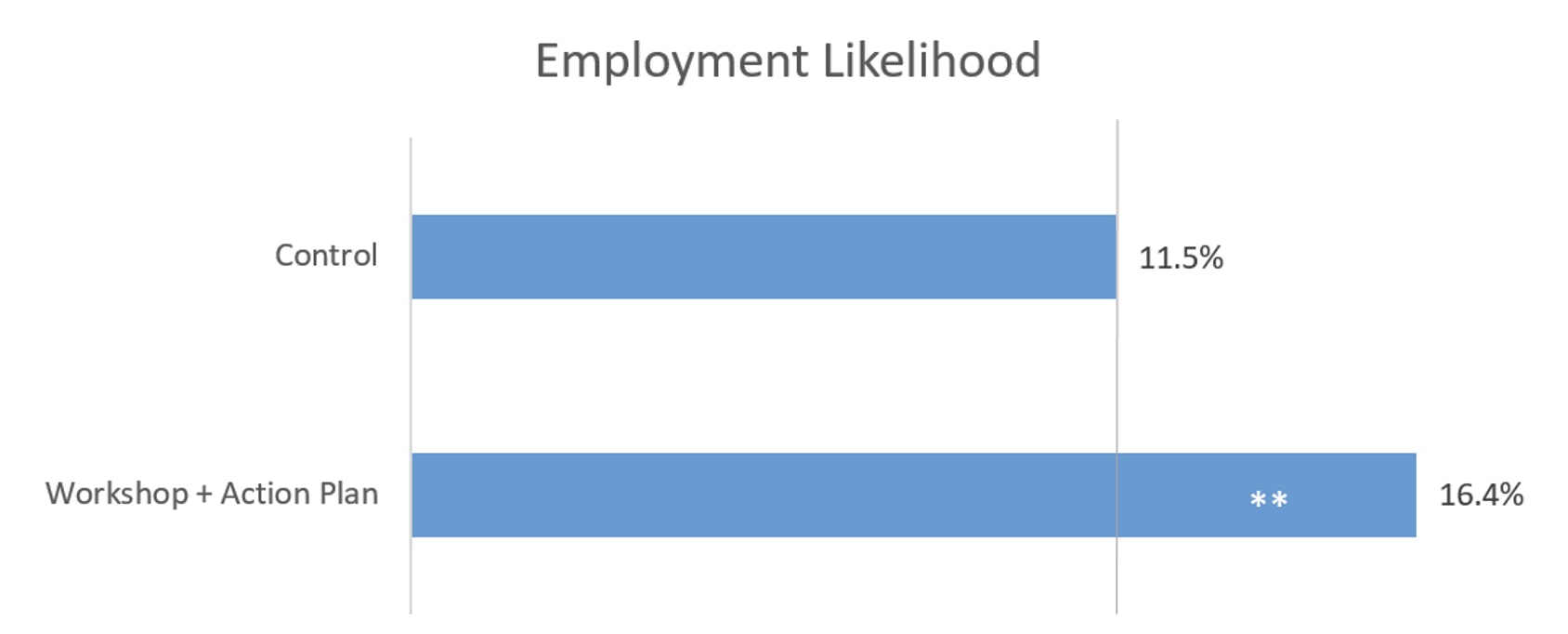

Job seekers in the action planning group use a wider range of search channels, particularly more formal search channels. Participants who completed the plan-making significantly increased the number of visits to employment agencies, the number of CVs submitted, the number of advertisements answered, and the frequency of online searching. To the extent that search channels have decreasing returns to efforts, a diverse portfolio of search activities is expected to improve job search effectiveness. Indeed, this resulted in significantly more job offers and a greater likelihood of employment for a given number of applications, increasing job search efficiency. Job seekers in the plan-making group received a higher number of responses from employers (24%) and job offers (30%), and were more likely to be employed (26%) at the time of follow-up.

Figure 3 Employment outcomes of treatment versus control group

Note: The figure shows the treatment effect of action plans on employment outcomes. Those who received both counselling and action plans during job search received more responses and job offers than those who did not receive either.

Our research shows that simple design tweaks like adding a plan template to a workshop address behavioural biases which may improve the effectiveness of active labour market policies (ALMPs) (Babcock et al. 2012). Plan-making is a low-cost, easy-to-implement addition to existing ALMPs, which have typically yielded modest results (Card et al. 2015, McKenzie 2017). Even in a context of high structural unemployment – where search efforts are thought to make little difference to employment chances – addressing the intention-behaviour gap in job search through action planning improves job search intensity, with a potential to translate into real employment results.

References

Abel, M, R Burger, E Carranza and P Piraino (2019), "Bridging the Intention-Behavior Gap? The Effect of Plan-Making Prompts on Job Search and Employment", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11(2): 284-301.

Babcock, L, W J Congdon, L F Katz and S Mullainathan (2012), “Notes on behavioral economics and labor market policy”, IZA Journal of Labor Policy 1(1): 1–14.

Caliendo, M, D A Cobb-Clark and A Uhlendorff (2015), “Locus of control and job search strategies”, Review of Economics and Statistics 97(1): 88–103.

Card, D, J Kluve and A Weber (2015), “What works? a meta analysis of recent active labor market program evaluations”, Journal of the European Economic Association.

DellaVigna, S and M D Paserman (2005), “Job search and impatience”, Journal of Labor Economics 23(3): 527–588.

Falk, A, D Huffman and U Sunde (2006), “Self-confidence and search”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 2525.

Hagger, M S and A Luszczynska (2014), “Implementation intention and action planning interventions in health contexts: State of the research and proposals for the way forward”, Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 6(1): 1–47.

McGee, A and P McGee (2016), “Search, effort, and locus of control”, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 126: 89–101.

McKenzie, D (2017), “How effective are active labor market policies in developing countries? a critical review of recent evidence”, The World Bank Research Observer 32(2): 127–154.

Rogers, T, K L Milkman, L K John and M I Norton (2015), “Beyond good intentions: Prompting people to make plans improves follow-through on important tasks”, Behavioral Science & Policy 1(2): 33–41.

Spinnewijn, J (2015), “Unemployed but optimistic: Optimal insurance design with biased beliefs”, Journal of the European Economic Association 13(1): 130–167.