Working together with one refugee worker for one week increases firms’ likelihood to hire more refugees by adjusting business owners’ beliefs about refugees’ skills

Addressing the pressing global challenge of integrating migrants, especially in the context of forced displacement, is crucial given that migrations are considered “one of the most important geopolitical phenomena of the century” (UN News 2023). The number of refugees and asylum seekers has risen significantly over the past decades, with UNHCR registering more than 100 million forcibly displaced people worldwide as of the end of 2022. This trend is unlikely to decrease in the future, partly due to factors such as instability in the migrants' countries of origin and the impact of climate change.

Refugees represent a vulnerable and significant population of potential workers in various societies. However, their integration into local labour markets often faces obstacles. One challenge is that refugees may lack the necessary skills for employment in host countries. Additionally, employers may be hesitant to hire them due to misconceptions about their abilities and negative attitudes toward their cultural differences compared to the destination countries. The failure to effectively integrate skilled refugee workers into local labour markets results in a waste of human potential and incurs substantial costs to societies.

While previous research has primarily focused on the first challenge, our study aims to address the second set of constraints by implementing and evaluating a programme that connects skilled refugees with firms in Kampala, the capital of Uganda. Drawing on the contact hypothesis in the workplace (Allport 1954, Mousa 2020, Lowe 2021, Corno et al. 2022), we investigate the following research question: does exposure to a single refugee worker increase firms' willingness to hire more refugees?

Matching skilled refugees with Ugandan employers

Uganda stands as one of the world's largest refugee-host countries, providing refuge to approximately 1.5 million displaced individuals. This legacy of welcoming refugees traces back to the Second World War (Lwanga-Lunyiigo 1993). Despite their longstanding presence in Uganda, only a limited number of refugees have ever been employed by Ugandan businesses. Our data indicates that less than 20% of firms in Kampala have ever hired a refugee, revealing a prevailing lack of experience with migrant workers among Ugandan enterprises.

Driven by this significant observation, we devised a programme to enhance Ugandan firms' exposure to refugee workers (Loiacono and Silva-Vargas, 2023). The programme comprises two main steps. Initially, we assess the practical skills of refugee workers across selected vocational sectors and provide them with certifications upon passing the examinations. Subsequently, we proceed to randomly match these skilled workers with Ugandan employers eager to offer week-long internships. Within this programme, some firms are randomly assigned to a treatment arm, where they interact with one of our refugee workers, while another group, the control arm, does not have any physical encounters with refugee workers. By implementing this intervention, we aim to gauge the impact of these internships on employers' readiness to hire new refugees.

Implementation of the intervention

To assemble a sample of skilled, working-age refugees, we collaborated with two refugee-led NGOs. Through these partnerships, we successfully enrolled over 500 refugees with vocational skills and work experience. Organising their skills tests involved close cooperation with the national Directorate for Industrial Training (DIT) and one of Kampala's largest vocational schools. Additionally, we created a sample of 535 firms that expressed interest in offering free internships to randomly selected refugee workers. More than half of these firms constituted the treatment group, actively engaging in one-week internships with the randomly matched refugee workers. However, it is important to note that not all refugees were able to participate in the internships we arranged for them, resulting in approximately half of the internships taking place. As a result, our study examines the experiment's effect using both the full sample (“Full” sample, represented by black bars in the graphs) and a subsample of firms whose internships were carried out (“Exposed” sample, depicted by gray bars).

Findings

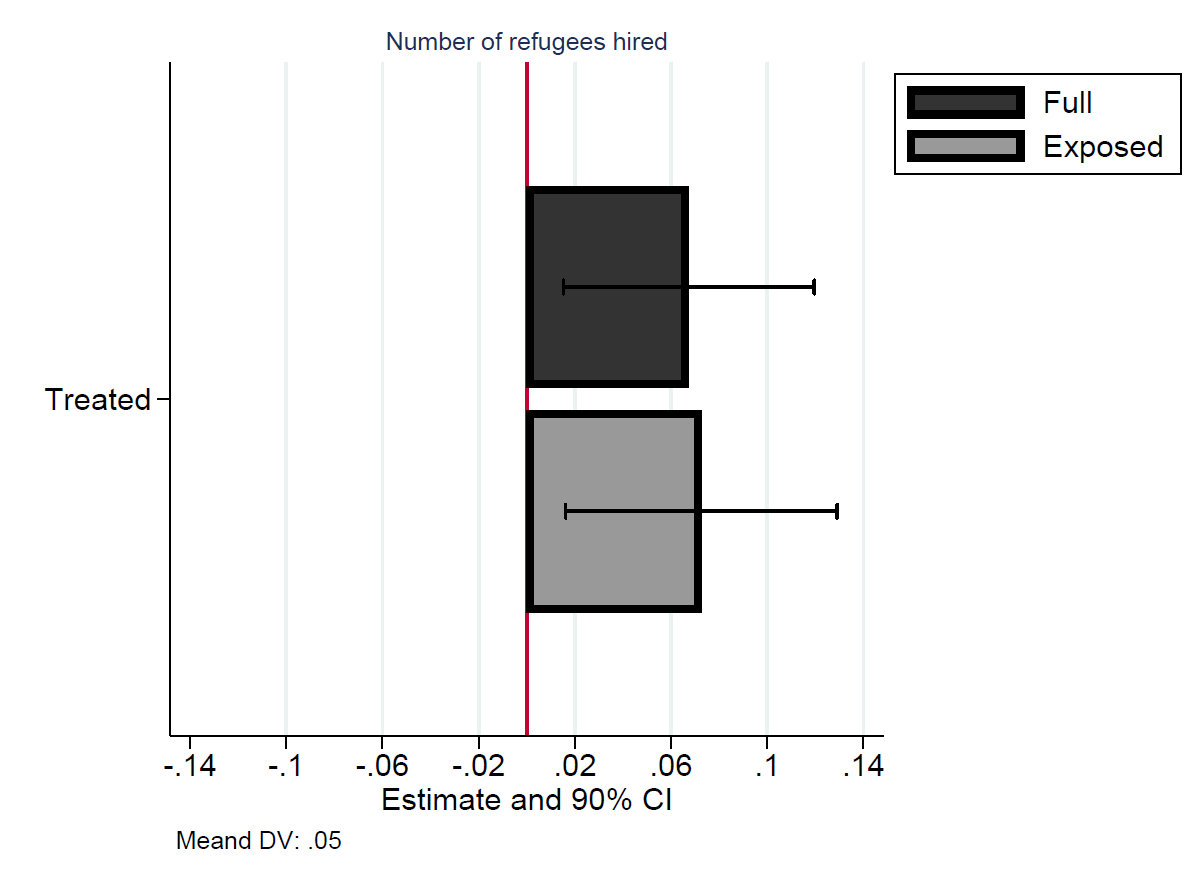

Our findings reveal that around 8 months after the internships, treated firms hired nearly three times as many refugee workers compared to firms in the control group (Figure 1). It is crucial to highlight that this effect is not solely attributed to the firms hiring the same refugee worker they were initially matched with. Instead, we have suggestive evidence indicating that these treated firms actively explored and connected with new workers from the refugee community.

Figure 1: The effect of exposure on number of refugees hired

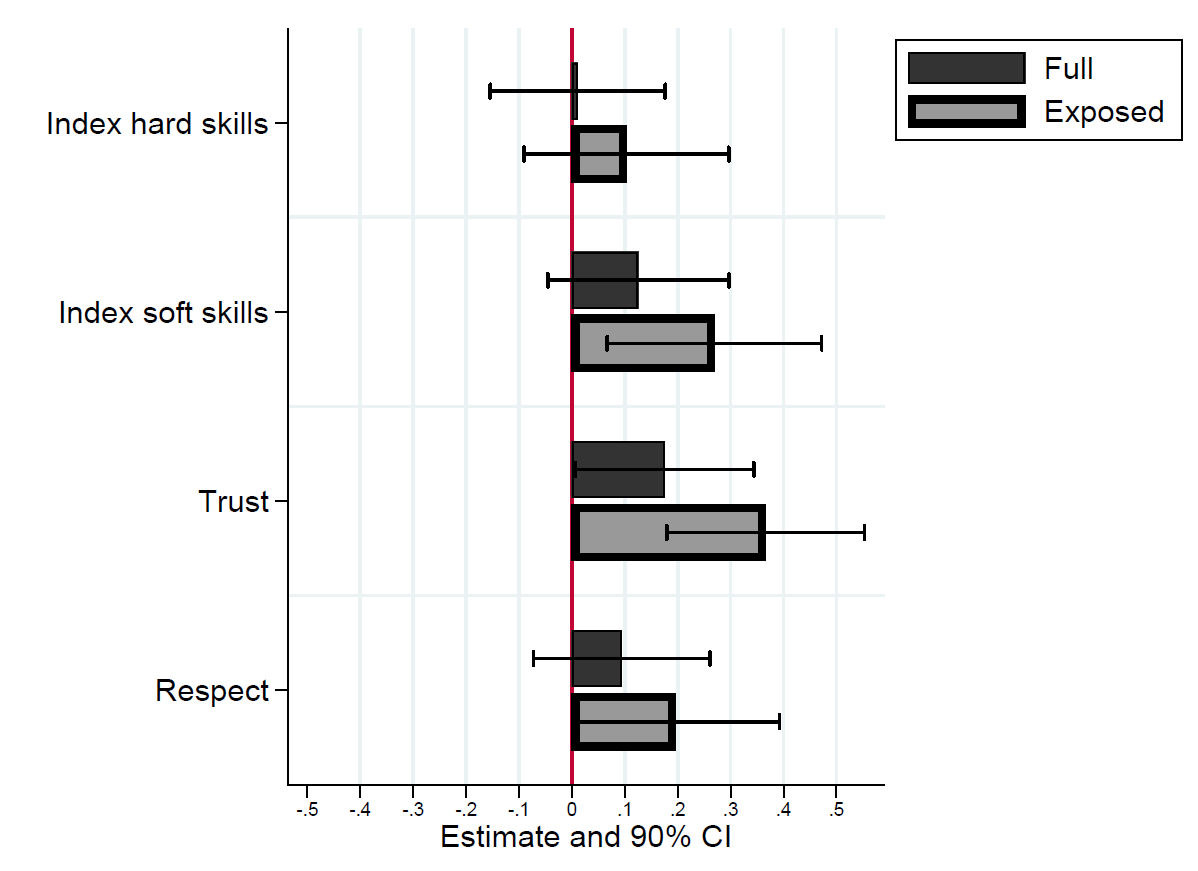

The observed effect can be attributed to an improvement in initially biased beliefs concerning the hard and soft skills of refugee workers. Employers who had the opportunity to work with one refugee for a week were more inclined to report enhanced beliefs regarding refugee workers compared to employers in the control group (Figure 2) at the end of the study.

Figure 2: The effect of the experiment on firms’ beliefs about refugee workers

Matching with the right attitude

Furthermore, we investigated the factors that influence employers' responsiveness to the intervention, aiming to identify the determinants of a successful match. Our findings indicate that both the employer's and the worker's attitudes towards each other's culture play a significant role in enhancing employers' willingness to hire more refugees. This effect was observed in both the short term (one month after exposure) and the longer run (over six months after the experiment).

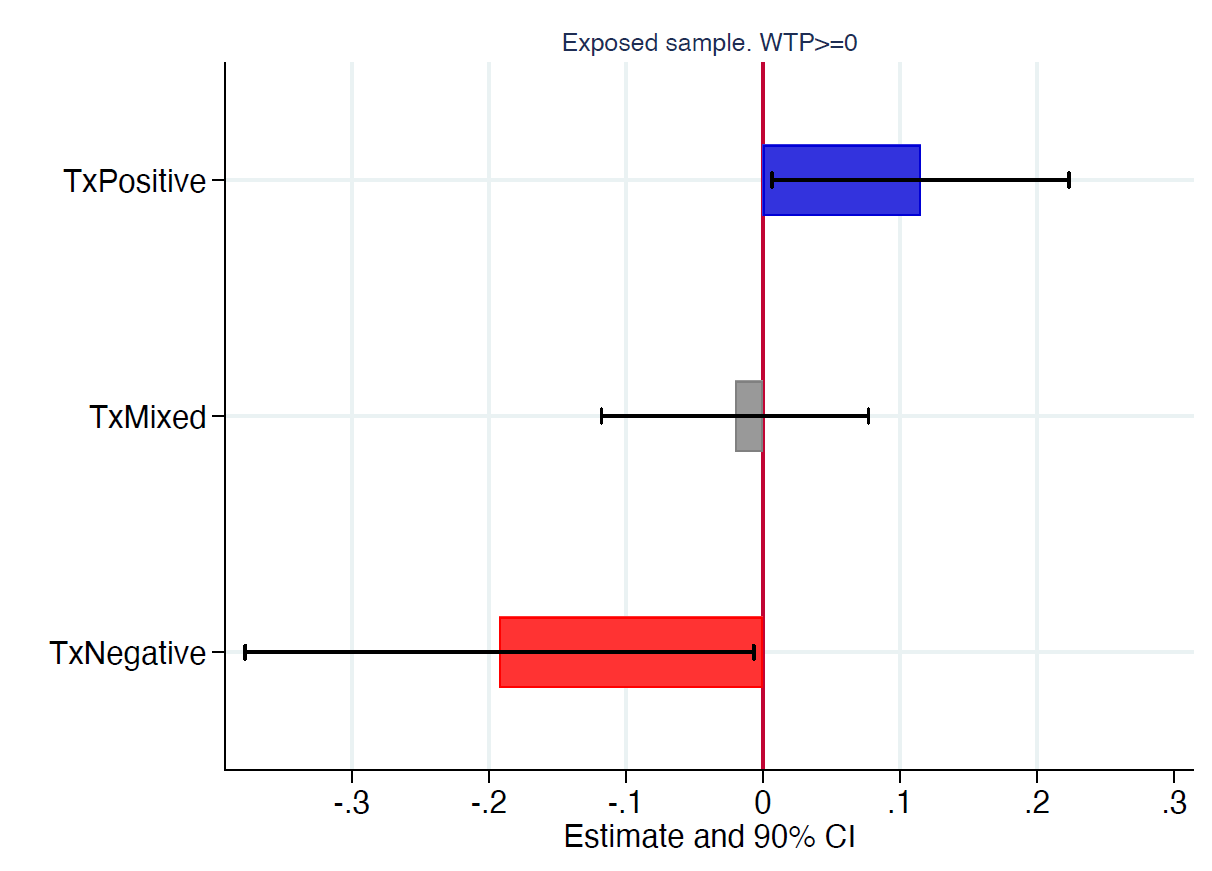

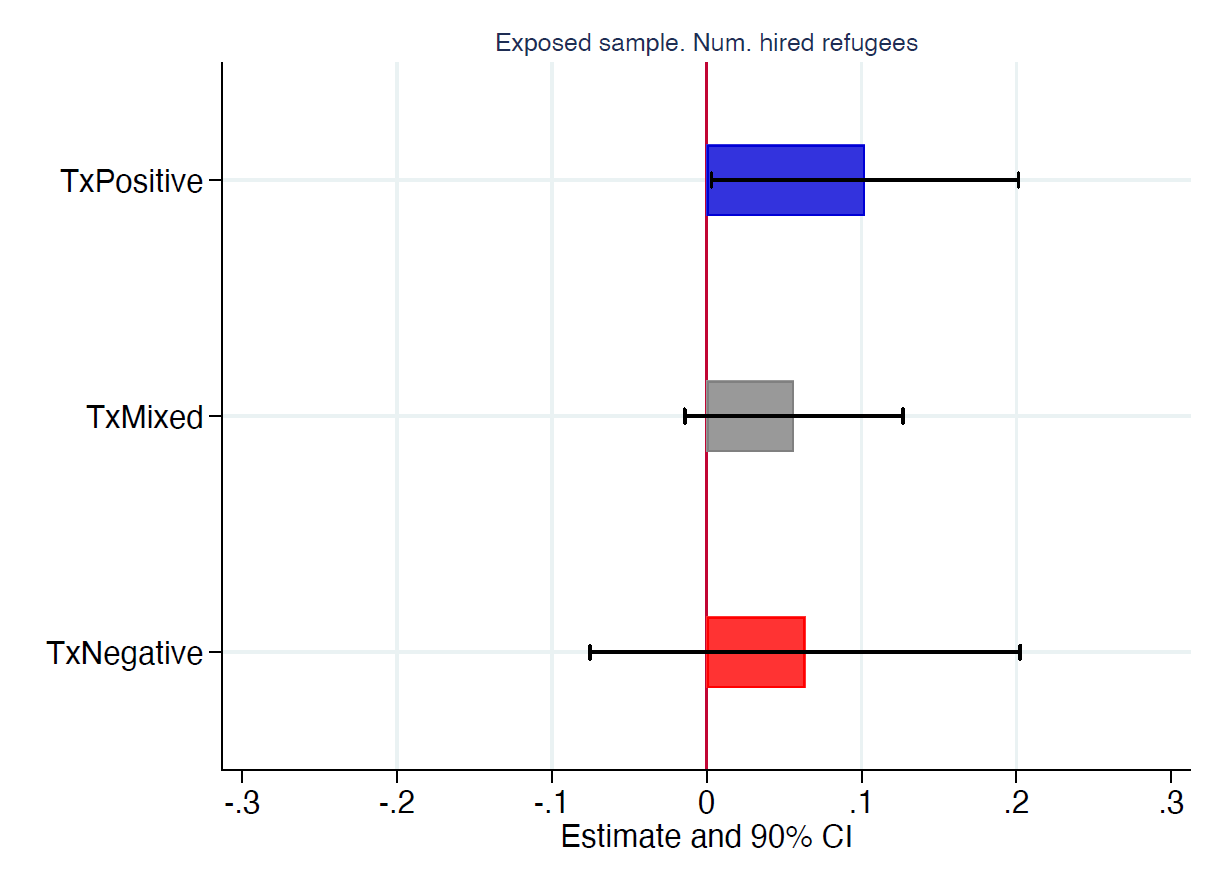

Specifically, employers who were already open to integrating refugees into Uganda and matched with refugee workers eager to be more integrated into the host society were more likely to hire more refugees (Figure 3). Interestingly, in the short term, employers with negative attitudes towards refugees, paired with workers holding negative attitudes towards Ugandans, displayed decreased willingness to hire a new refugee. We have explained this finding by providing suggestive evidence that in such cases, employers may have exerted minimal effort or no effort at all in learning about the quality of refugees, and workers may not have made sufficient efforts to perform well on the job. In essence, these internships resulted in a “negative” contact, which led to a reduction in employers' willingness to initiate future contacts with refugees (Paolini et al. 2010, Barlow et al. 2012, Meleady and Forder 2019, Lepage 2022).

Figure 3: Matching with the right attitude

Panel A: Short-term

Panel B: Longer-term

Policy takeaways

A lack of labour market integration of refugees can be particularly burdensome in low-income country settings where labour markets often do not function optimally, and national resources are already stretched thin. However, our research demonstrates that, when provided with an opportunity, local employers can gain insights into the true abilities of skilled refugee workers, resulting in a positive impact on their willingness to hire other workers from the same group.

When given a chance, migrants and refugees can become valuable assets to firms, leading to an increased demand for these groups of workers. Rather than focusing solely on strategies to halt migrations, governments should consider investing in recognising the existing skills of refugees and facilitating their integration into local firms. Embracing such an approach can lead to more successful labour market integration and foster a mutually beneficial relationship between refugees and host countries' economies.

References

Allport, G W (1954), The nature of prejudice, Addison-Wesley.

Barlow, F K, S Paolini, A Pedersen, M J Hornsey, H R M Radke, J Harwood, M Rubin, and C G Sibley (2012), “The Contact Caveat: Negative Contact Predicts Increased Prejudice More Than Positive Contact Predicts Reduced Prejudice,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38: 1629–1643.

Battisti, M, Y Giesing, and N Laurentsyeva (2019), “Can job search assistance improve the labour market integration of refugees? Evidence from a field experiment,” Labour Economics, 61: 101745.

Caria, S, G Gordon, M Kasy, S Quinn, S Shami, and A Teytelboym (2020): “An Adaptive Targeted Field Experiment: Job Search Assistance for Refugees in Jordan,” SSRN Electronic Journal.

Corno, L, E La Ferrara, and J Burns (2022), “Interaction, Stereotypes, and Performance: Evidence from South Africa,” American Economic Review, 112: 3848–3875.

Lepage, L-P (2022), “Experience-based Discrimination,” Working paper.

Loiacono F and M Silva-Vargas (2023): “Matching with the Right Attitude: The Effect of Matching Firms with Refugee Workers”. Working paper.

Lowe, M (2021): “Types of Contact: A Field Experiment on Collaborative and Adversarial Caste Integration,” American Economic Review, 111: 1807–1844.

Lwanga-Lunyiigo, S (1993), “Uganda’s long connection with the problem of refugees: Fromthe Polish Refugees of World War II to the Present”. Mimeo. Makerere University.

Meleady, R and L Forder (2019), “When contact goes wrong: Negative intergroup contact promotes generalized outgroup avoidance,” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 22: 688–707.

Mousa, S (2020): “Building social cohesion between Christians and Muslims through soccer in post-ISIS Iraq,” Science, 369: 866–870.

Paolini, S, J Harwood, and M Rubin (2010), “Negative Intergroup Contact Makes Group Memberships Salient: Explaining Why Intergroup Conflict Endures,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36: 1723–1738.

UN News (July 2023), “UNHCR, IOM outline new approach to assist growing number of migrants”, Available at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/07/1139047.