Policies 150 years ago that allowed large landlords to obtain thousands of square miles of land lowered investment and property values into the 21st century

Land is the main productive asset in agrarian economies, and many of the earliest economic debates asked how to efficiently distribute it. Most societies feature a mix of smallholders, who work land they personally own, and larger owners, who become landlords by renting to poorer tenant farmers.

Land distribution and economic development

Adam Smith wrote disparagingly of the “natural selfishness” of the large landowners and the inefficiency of the sharecropping contracts they employed (Smith 1776). More recent arguments, however, emphasise the benefits of flexible contracts and the opportunities for large owners to create economies of scale (Cheung 1969, Allen 1988). For his part, Smith also believed that the market’s invisible hand could ameliorate the downsides of an unequal land distribution (Smith 1759).

Sorting through these competing theories is difficult because a complex process determines whether land ownership is dispersed or concentrated in the hands of a few. As a result, different owners are likely to own different kinds of properties, even adjusting for the measures of quality that a researcher can observe (Benjamin 1995). Additionally, the historically-minded would want to know not only how the distribution of land affects the economy today, but whether and how it can shape growth over the long run.

Land policies on the American frontier

My paper (Smith 2020) studies these questions in the American West for two reasons. First, its frontier status meant that most communities were founded in a short period of time, making it possible to see the impact of initial conditions on later developments. Second, a patchwork of contradictory land policies meant that both “pioneer” farmers and affluent landlords ended up with similar tracts of land. It is important to note, however, that these academic advantages came at a great human cost. Frontier communities could only be created as blank slates because of the comprehensive displacement of their indigenous populations.

Two major American land policies allow me to compare smallholders and landlords:

- The Homestead Act

In the midst of the Civil War, Congress passed the 1862 Homestead Act to promote frontier settlement by small farmers. Before 1862, affluent settlers could potentially obtain unlimited amounts of land. After 1862, they were typically restricted to 160 acres. This figure is large relative to typical plots in many developing countries today, but the quality of the untilled soils in many parts of the American plains meant that few Homesteaders could expect to become wealthy.

- Railroad land grants

Paradoxically, the government soon undermined its commitment to the Jeffersonian ideal of small, independent farmers. Eager to industrialise and unwilling to raise taxes, it used thousands of square miles of the frontier as payment for railroad construction. These land grants went far beyond what was needed to lay tracks, regularly including places twenty or more miles from any construction. In other words, this was a pure in-kind payment.

Railroad companies auctioned these lands off in blocks without restriction, meaning that buyers were disproportionately affluent and inclined toward large properties. Together, the Homestead Act and railroad land grants transferred about 750,000 square miles of land – 25% of the area of the continental United States.

An essentially random land assignment

These land policies are a convenient setting to study land concentration because of the structured yet arbitrary system for dividing plots. The two policies were often interspersed in a “checkerboard” pattern, meaning that every other square mile of land would go to Homesteaders, while the remainder were sold by the railroads. The Homestead squares would be subdivided among multiple owners, while railroad buyers could purchase multiple squares, creating diagonally-adjacent properties they would connect over the years.

Administratively, this was an easy pattern to create. Each square mile of land had been given an identification number in the initial surveys mapping the frontier, and the law simply gave the odd-numbered squares to railroads. The arbitrary nature of this distribution meant that the land initially given to smallholders and landlords did not systematically differ in quality, location, or institutional detail. This is a critical advantage for research as it allows me to isolate the impact of the owners from other confounding factors.

Figure 1 The checkerboard pattern of land distribution

Note: Railroad lands near the Union Pacific line in Nebraska. Each pixel is roughly one square mile.

Under ideal conditions formalised in the Coase Theorem, the initial allocation of assets should be irrelevant for their final pattern of use, once Adam Smith’s invisible hand guides owners to the efficient distribution. But despite a robust market for land over subsequent generations, railroad plots remained more concentrated and more likely to be worked by tenant farmers. This gap does shrink over time, however, implying that the invisible hand still played an important role. Coase never felt the real world would match the conditions of his theorem, but over the very long run it seems to come close.

Figure 2 Land concentration over time

Note: Average ownership size over time, Banner County, Nebraska (subsample).

Historical land concentration reduced current value

Paul Wallace Gates, one of the preeminent historians of the American frontier, argued that large landlords and their system of tenancy, “did not always result in the best use of the land” (Gates 1942). I find quantitative support for this claim using a large collection of modern property tax assessments covering about 380,000 square miles of land in six states, as well as a smaller database of historical assessments.

According to standard pricing theory, the value of property should reflect the net present value of benefits it gives to its owners, meaning it can serve as a holistic measure of worth. On average, modern property values in the former railroad lands are 4.4% lower than the adjacent plots settled by smallholders.

A negative impact is present for all the states and railroad companies in my sample, meaning it does not stem from the idiosyncratic laws or policies of one specific place. The effect is also present across most of the value distribution when estimated with quantile regressions, meaning there are no obvious cases where landlords outperformed their counterparts.

Implication: The role of land investment

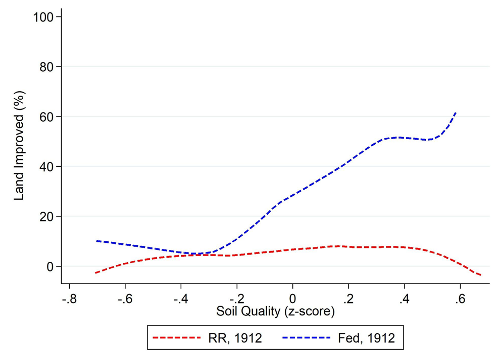

The lower property values of former landlord properties derive from low levels of investment historically. From early 1900s assessments, I can measure the fraction of land marked as “improved,” meaning owners had invested in clearing it to grow crops. According to these records, large landowners often left their properties unimproved for open-range cattle grazing, regardless of land quality.

In contrast, smallholders carefully selected the best parts of their properties to improve. Future owners converged to the smallholders’ choices – though even today railroad lands lag a bit behind in terms of these investments.

Figure 3a Percentage of land improved by settlement type in 1912

Figure 3b Percentage of land improved by settlement type in 2017

Note: Railroad (RR) versus federal (Fed) land improved, Morrill County, Nebraska (subsample).

Conclusion: Unequal land distribution and low investment

In my paper, I use other data to argue the source of landlords’ low investments was their crop share agreements (Smith 2020). Such arrangements were once widely used in developed countries and are still common in developing countries today. Economic theory dating back to Marshall has argued that because these contracts divide any increases in output, they lower the incentives of individual agents to invest. Using the essentially random provision of 1800s American land to different owners, I provide new evidence for this view.

This is hardly the last word on land concentration, of course; in other contexts, different dynamics may have prevailed. The United States lacked the feudal tradition present in many countries, potentially explaining why I find few impacts on the political system. Still, the possibility that an unequal distribution of land can shape not only the present, but the long-run development of an economy, opens up many avenues for future research.

References

Allen, RC (1988), “The Growth of Labor productivity in Early Modern English Agriculture”, Explorations in Economic History 25(2):117–146.

Benjamin, D (1995), “Can Unobserved Land Quality Explain the Inverse Productivity Relationship?”, Journal of Development Economics 46(1):51–84.

Cheung, S (1969), The Theory of Share Tenancy, University of Chicago Press.

Gates, P W (1942), “The Role of the Land speculator in Western Development”, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 66(3):314– 333.

Smith, A (1759), The Theory of Moral Sentiments.

Smith, A and E, Cannan (2003), The Wealth of Nations, Bantam Classic.

Smith, C (2020), "Land Concentration and Long-Run Development in the Frontier United States".