Subsidised government-constructed housing increases income, education, and employment in Mumbai

Governments in developing countries often construct homes on public land and then sell them at a subsidised price to low-income households. These programmes exist in countries including, but not limited to, India, Brazil, Uruguay, Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia, and South Africa. They are particularly common in India, where they are spearheaded by state-level housing boards in every state and in every major city. Aside from transferring wealth through the subsidy, these interventions help families purchase an asset that forms the cornerstone of wealth accumulation.

Existing studies suggest the programmes lead to limited welfare gains for beneficiaries, though this may be because they focus on programmes that require relocation. In Ahmedabad (India), for example, Barnhardt et al. (2017) find that beneficiaries’ social networks are broken when they move far from their original neighbourhoods. In South Africa, Picarelli (2019) finds that household economic outcomes worsen when households are relocated from labour markets.

A programme in Mumbai that does not require relocation

In a new paper (Kumar 2021), I study a programme in Mumbai, India that allows households to benefit from subsidised housing without having to relocate. As implemented in Mumbai, the programme allocates housing through a randomised lottery, allowing for the causal identification of its effect on applicants. Using an original survey (conducted in 2017) of 834 households in which I traced and interviewed a sample of winning and non-winning applicants, I estimate the programme’s impact on those who won homes in 2012 and 2014.

In the short term, beneficiaries can rent out their home. Rental income for households that do not relocate is on average, US$50 per month net of mortgage. In the long term, they can resell the home after ten years. The estimated difference between the subsidised and market prices ten years after the subsidised sale ranges from $10,000 to $56,000, depending on the apartment’s location. The programme therefore generates both (1) short-term housing benefits or income, and (2) large shifts in long-term wealth.

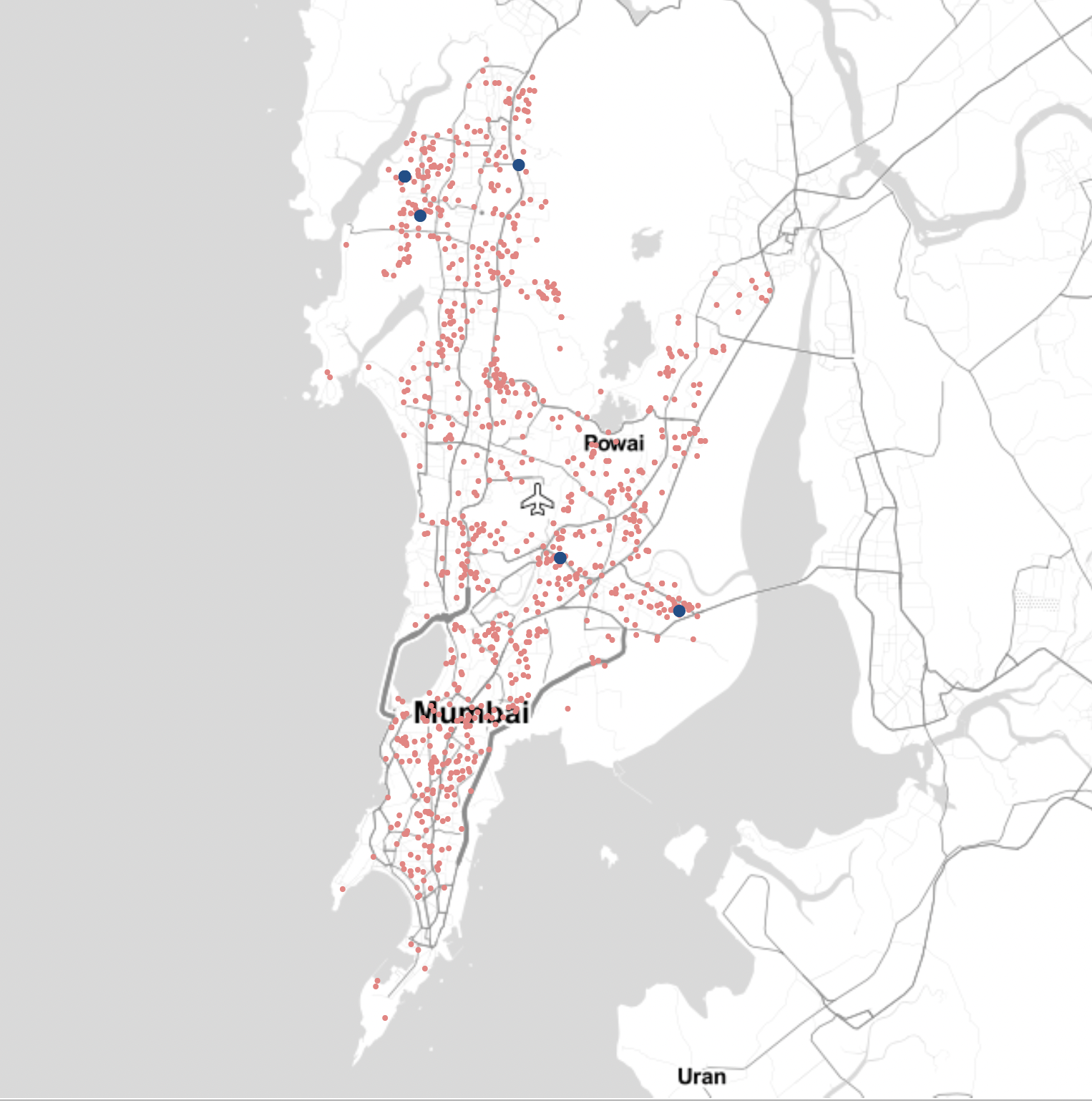

Furthermore, because households can choose whether to relocate, the programme design prevents housing location from undermining its economic gains. Figure 1 shows the location of the lottery housing along with applicants’ addresses at the time of application.

Figure 1 Household locations

Note: Location of the addresses of households in the sample (small pink dots) along with the location of apartment buildings (large blue dots) at the time of application

Impact of the programme on housing quality, income, and education

Housing quality improves along with an increase in income

I explore the effect of the programme on housing quality, income, and non-housing asset ownership. I find improvements in housing quality as measured through the quality of roofs and whether or not houses have their own water supply and toilets. I also record an increase in reported income among beneficiaries. This could be for many reasons, including increased employment (discussed below) and income from rent for those who choose not to live in the housing.

Increase in educational attainment and employment

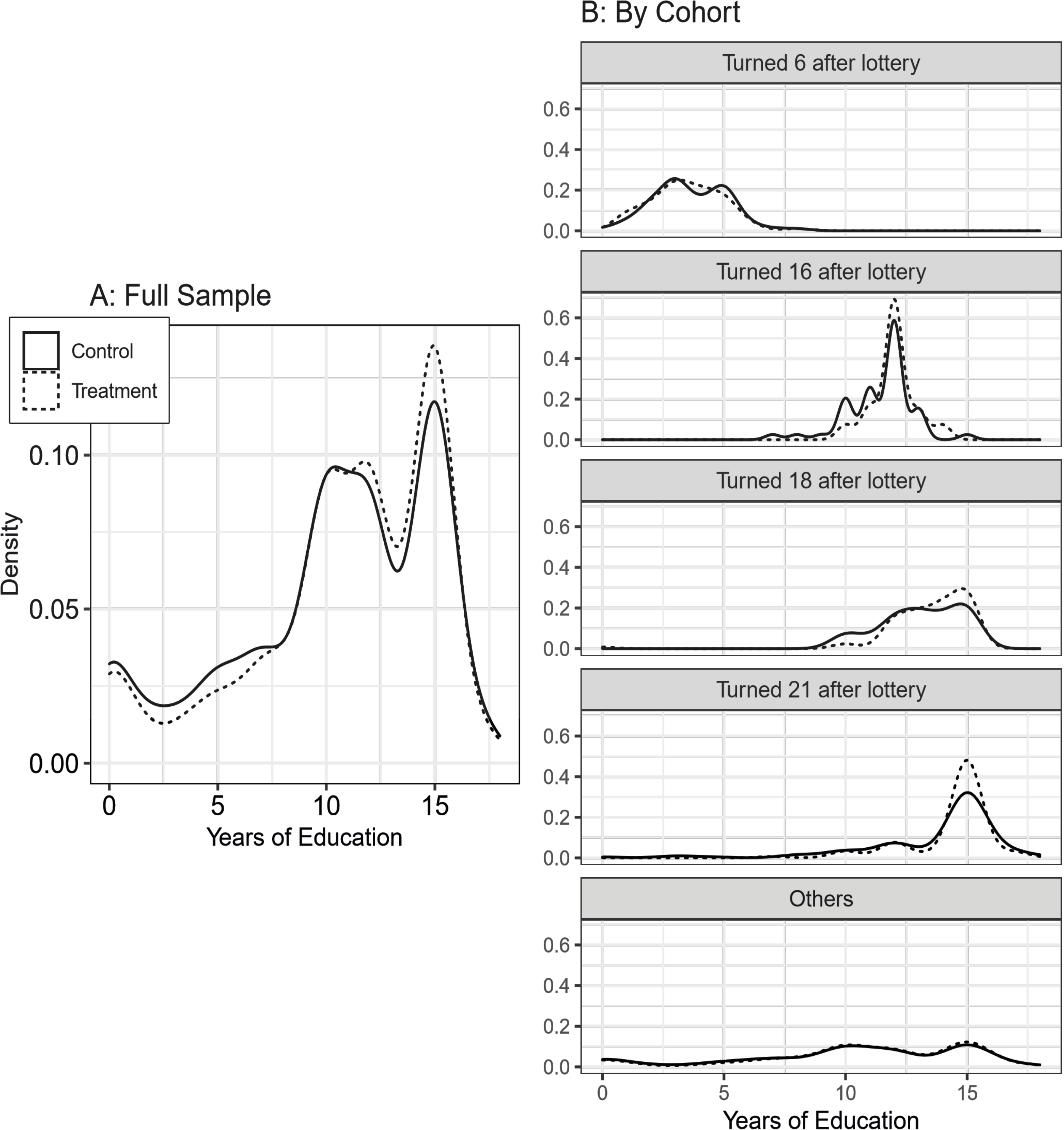

There are large gains in education and employment just three to five years after the lottery is implemented. The intervention increases individual years of education by 0.6 years, a large gain considering that the non-beneficiaries have about ten years of education on average. This effect seems to be driven by an increase in beneficiaries’ likelihood of completing secondary (grades 10 and 12 in the Indian context) and post-secondary education (Figure 2, Panel A). These effects are largest among those passing through grades 10, 12, and college after the lottery (Figure 2, Panel B).

The programme further increases employment among individuals by 4.4 percentage points over a mean employment rate of 46% among non-beneficiaries. The same groups – namely, school-age youth – among which large education gains are observed also have better employment outcomes later on, suggesting that the education gains drive employment gains.

Figure 2 Distribution of individual years of education for the full sample and different age cohorts

Note: Large education gains kick in after 3-5 years of winning the lottery that are driven by among those passing through grades 10, 12, and college after the lottery.

Improved mental wellbeing

I also find that beneficiaries have better attitudes about their finances and futures compared to non-beneficiaries. They report feeling happier about their financial situations, expect better lives for their children, are more likely to plan to stay in the city permanently, and have slightly more ‘individualistic’ attitudes. These changes might be driven by the change in households’ short-term and long-term wealth, as income and wealth transfers can decrease stress and make it easier to focus on long-term goals (Haushofer and Fehr 2014).

Potential mechanisms

To what extent are these effects driven by opportunities in the new neighbourhoods or moving to houses for which beneficiaries possess legal titles (as opposed to living in an illegal, informal, or squatter settlement)? Surprisingly, beneficiaries on average live in neighbourhoods with worse school quality and lower rates of literacy and employment than non-beneficiaries, suggesting that the differences are not driven by relocating to areas with better employment and educational opportunities. Effects may also be driven by changes in housing legality, because households may spend less time making sure they are not evicted from their homes and more time working or going to school (Franklin 2020). However, this seems unlikely as effects are smaller or even negative among those living in informal or illegal housing at baseline (possibly because beneficiaries living in informal housing are more likely to relocate to the worse neighbourhoods). There are many other possible mechanisms driving the findings, including shifts in how households spend money (due to increases in short-term income and long-term wealth) or the changes in attitudes about the future discussed above.

Overall, the study finds large economic effects of a common policy. It may also have important effects on other aspects of beneficiaries’ lives. For example, in a companion study (Kumar forthcoming) I find that winning the housing lottery increases local-level political participation.

Policy implications

This in-kind transfer affects many outcomes typically of interest in studies of cash transfer policies. The education and employment effects are at least as large as the conditional cash transfers that specifically target these outcomes (Araujo et al. 2016, Parker and Vogl 2018). Overall, the study suggests that in-kind transfers can have benefits comparable to cash transfers when markets for rental or resale work well.

Moreover, subsidised housing programmes may be particularly appealing for policymakers. They incur few direct costs on governments because the sale price of the homes covers construction and marketing costs. Land-use laws may further limit the theoretically high opportunity cost of building subsidised homes on urban land. In the programme studied here, for example, housing was constructed on land earmarked for social welfare purposes. They may also be politically expedient for implementers. Gilbert and Ward (1985, 5–6) argue that public housing provides visual evidence that the government is providing for the poor, creating construction jobs, and providing homes for officials and politicians’ supporters. Bueno (forthcoming) further shows that mayors in Brazil actively claim credit for housing programmes prior to elections.

A key difference between this programme and others previously studied – the ability of beneficiaries to sell or rent out the homes – may account for the relatively large effects observed. This programme also differs from programmes common in the US in that the public housing is for rent, rather than sale. These differences suggest that multiple programme parameters (others might include the subsidy size, location, or eligibility requirements) can affect their gains for beneficiaries, indicating the need for future research. Though these policies are widespread, there are still relatively few studies on their effects. As they tend to be oversubscribed, they are often implemented through lottery systems particularly in India. This feature should facilitate causally identified future studies on long-term impacts, mechanisms, and the effects of important programme parameters.

References

Araujo, M C, M Bosch, and N Schady (2016), “Can Cash Transfers Help Households Escape an Inter-Generational Poverty Trap?”, NBER Working Paper 22670.

Barnhardt, S, E Field, and R Pande, (2017), “Moving to Opportunity or Isolation? Network Effects of a Randomized Housing Lottery in Urban India”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9(1): 1–32.

Bueno, N (forthcoming), “The Timing of Public Policies: Political Budget Cycles and Credit Claiming”, American Journal of Political Science.

Franklin, S (2020), “Enabled to Work: The Impact of Government Housing on Slum Dwellers in South Africa”, Journal of Urban Economics 118: 103265.

Gilbert, A and P Ward (1985), Housing, the State and the Poor: Policy and Practice in Three Latin American Cities, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Haushofer, J and E Fehr (2014), “On the Psychology of Poverty”, Science 344(6186): 862–67.

Kumar, T (2021), “The Housing Quality, Income, and Human Capital Effects of Subsidized Homes in Urban India”, Journal of Development Economics 153: 102738.

Kumar, T (forthcoming), “Home-Price Subsidies Increase Local-Level Political Participation in Urban India”, Journal of Politics.

Parker, S W and T Vogl (2018), “Do Conditional Cash Transfers Improve Economic Outcomes in the Next Generation? Evidence from Mexico,” NBER Working Paper 24303.

Picarelli, N (2019), “There Is No Free House”, Journal of Urban Economics 111: 35–52.