International labour migration and related remittances increase human capital attainment in rural areas, and over the long run trigger a shift of jobs out of farming towards the service sector

Labour migration acts as one of the conduits for capital to flow from rich to poor countries. In 2019, remittances from international migrants were on course to be the largest source of foreign capital received by developing countries, overtaking both FDI and development aid flows (World Bank 2019). A recent article in the popular press frames these remittances as the “hidden engine of globalisation”.1 Yet, as Clemens and McKenzie (2018) note, “economists remain surprisingly unsure of its (remittances) broad development effects”.

Studying the long-run effects of labour migration shocks in Africa

In two recent projects, we investigated how sending regions are affected by labour migration, by collating historical data on migration flows in Africa and by taking a long-run view of economic effects in source regions. In particular, we study a period of widespread, regulated international labour migration between Malawi and South Africa. We used census data to follow rural communities that were differentially exposed to large labour migration shocks and analysed how education and labour market outcomes evolved in the three decades after these shocks.

Our findings show that in areas with more circular (return) labour migrants, children attained higher levels of education. Moreover, in areas that received more remittances per migrant, workers shifted out of farming and into higher value-added service work over the long run. Our work illustrates the persistent effects of the end of international labour migration and remittance flows on the labour market structure of rural economies. Investments in the education of the next generation of workers appears to have been a key channel for these changes.

Shocks to international migration from and remittances to Malawi: Historical context

Historically, South Africa’s mining industry recruited millions of men from the broader southern African region for contract work on gold mines. These mining jobs were lucrative relative to income-earning possibilities in home countries and many men took up these jobs on two-year contracts. Workers were contractually obliged to receive two-thirds of their earnings upon repatriation. As a result, many rural local economies received large capital inflows when migrants returned home. One of the countries linked into this system of legal, international labour migration was Malawi. We collected archival data on the flows of men and money between Malawi and South Africa to investigate what happened to rural sending areas after a period of mass migration.

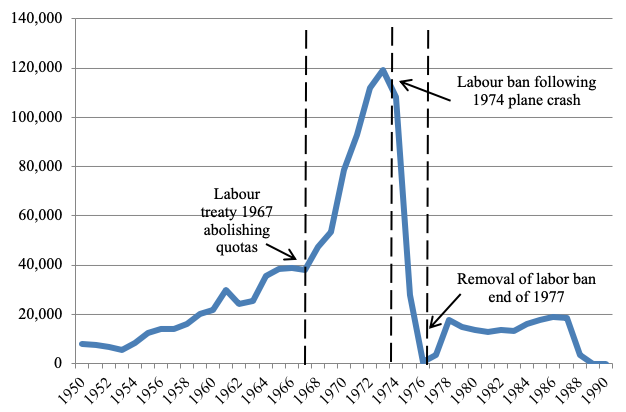

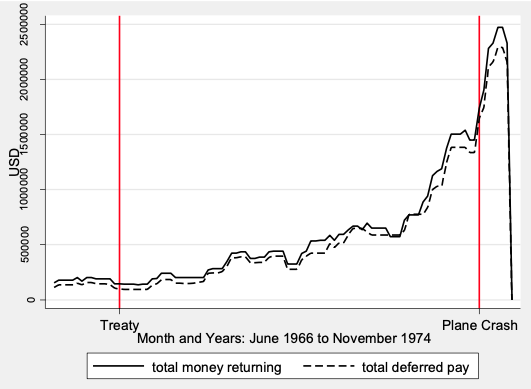

In the late 1960s, Malawians flocked to the gold mines when local quotas on recruiting labour were removed. This migration surge was soon curtailed by a ban on recruiting and an immediate repatriation of migrants in response to a plane accident in the early 1970s that killed returning miners. Between 1967 and 1973, mine migration increased by 200% and then fell to zero (Figure 1). Remittances followed a similar pattern (Figure 2). Total remittances were large – in the order of $53 million, triple the amount of total US foreign aid sent to Malawi in the mid-1970s. We exploit these unexpected changes in the ability to migrate internationally to identify the effects of migration and remittances on the local Malawian economy.

Figure 1 Annual employment of Malawians in South African mines, 1950-1994

Source: Dinkelman and Mariotti (2016)

Figure 2 Total remittances returned to Malawi, 1966-1974

Source: Dinkelman et al. (2020)

Reading, writing, and remittances: Circular migration raised education levels of the next generation

In Dinkelman and Mariotti (2016), we compared total years of education of adults who would have been eligible for primary schooling during the migration shock years across areas with and without mine labour recruiting stations. Areas with recruiting stations tended to send more migrants because living near a station made it easier to sign up for mining jobs. We show that these recruiting stations were placed as if randomly, and show that the high migrant-sending areas were not observably different on economic or geographic variables that might have separately predicted higher levels of educational investments. We also controlled for unobserved differences between recruiting and non-recruiting areas using older and younger age groups who were ineligible for primary school during these years as the comparison cohorts.

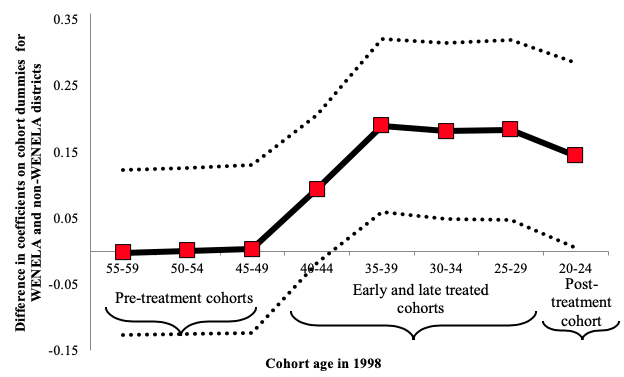

Figure 3 shows how exposure to these migration shocks affected schooling gaps across sending areas for eligible and ineligible cohorts of adults. The gap in years of schooling between areas with and without recruiting stations was zero before the migration shock (ineligible pre-treatment cohorts), but becomes large for cohorts eligible for school during the migration shocks (early and late treated cohorts). After the end of migration, among younger groups (ineligible post-treated cohorts) the education gap across districts again shrinks. Twenty years after the end of migration, human capital is 4.8-6.9% higher among eligible cohorts in communities with the easiest access to migrant jobs.

Figure 3 Estimated differences in education by cohort and recruiting station status of district

Source: Dinkelman and Mariotti (2016).

Note: WENELA districts are those with mine labour recruiting stations.

From farming to services: Circular migration led to structural changes in the labour market

In Dinkelman et al. (2020), we consider the role that returning migrant money played in affecting the sector in which people chose to work. Using the same panel of district-level data, we conditioned on total migrants from an area and estimated the effect of a district receiving varying amounts of migrant money by the mid-1970s. Different regions sent migrants at different times. Because mining wages were rising over time (in line with global gold prices), this meant that districts sending more of their migrants later received more total remittances per migrant.

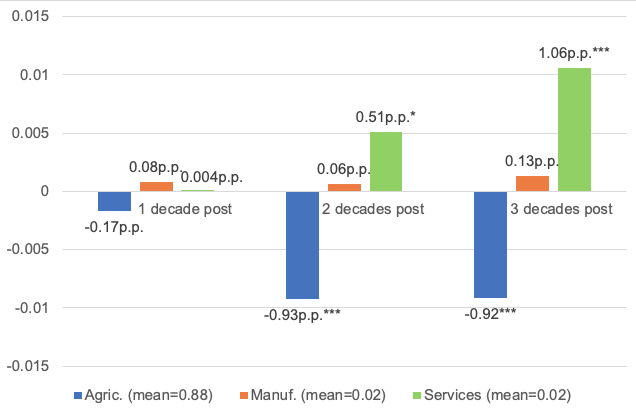

Our findings indicate that labour markets that received more migrant capital saw sustained shifts out of farming and into more capital-intensive and higher value-added non-farm service sectors over the next thirty years. These results are strongest and largest for women. Figure 4 shows the magnitude and persistence of the impacts on women. For an additional $1 million received through migration, the share of women working in agriculture fell by 0.17 percentage points in the first decade; then by almost one percentage point in each of the next two decades. Women shifted into services, particularly retail.

These shifts in sector of work are likely linked to how remittances are spent in receiving districts. We find that the same regions that received more migrant remittances (conditional on total migrants) had also acquired more human capital and non-farm physical capital. In contrast, there is no evidence that the remittance shock led to more investments in farm capital.

Figure 4 Effects of receiving an additional $1 million in remittances on sector of work for women

Source: Results are from Dinkelman et al. (2020)

Conclusion: Migrants and remittances matter for economic outcomes of sending countries in the long run

Our historical evidence from Malawi demonstrates that temporary international migration and remittances can affect rural labour markets in the long run. Our results are policy-relevant for countries considering temporary or seasonal labour migration programmes. They suggest that legal, time-limited migration could be a practical way for communities to accumulate capital. By focusing attention on boosting the ability of international migrants to invest in the education of their children2 and in non-farm capital, such labour-rich, resource-poor countries may be able to trigger persistent and positive impacts on the structure of work in rural economies.

References

Clemens, M and D McKenzie (2018), “Why don't remittances appear to affect growth?”, The Economic Journal 128(612): F179–F209.

Dinkelman, T, G Kumchulesi and M Mariotti (2020), “Labor migration, capital accumulation, and the structure of rural labor markets”, Working Paper.

Dinkelman, T and M Mariotti (2016), “The long-run effects of labor migration on human capital formation in communities of origin”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 8(4): 1-35.

Theoharides, C (2017), “Manila to Malaysia, Quezon to Qatar: International migration and its effects on origin-country human capital”, Journal of Human Resources 53(4): 1022-1049

The World Bank (2019) “Migration and Remittances Brief 31: Recent developments and outlook”, KNOMAD, April.

Yang, D (2008), “International migration, remittances and household investment: Evidence from Philippine migrants’ exchange rate shocks”, The Economic Journal 118(528): 591–630.

Endnotes

1 https://ig.ft.com/remittances-capital-flow-emerging-markets/

2 See also important work on this link by Yang (2006) and Theoharides (2017), amongst others.