Family ties to non-elected bureaucrats distort public employment outcomes, and standard anti-nepotism policies are ineffective at preventing their negative influence

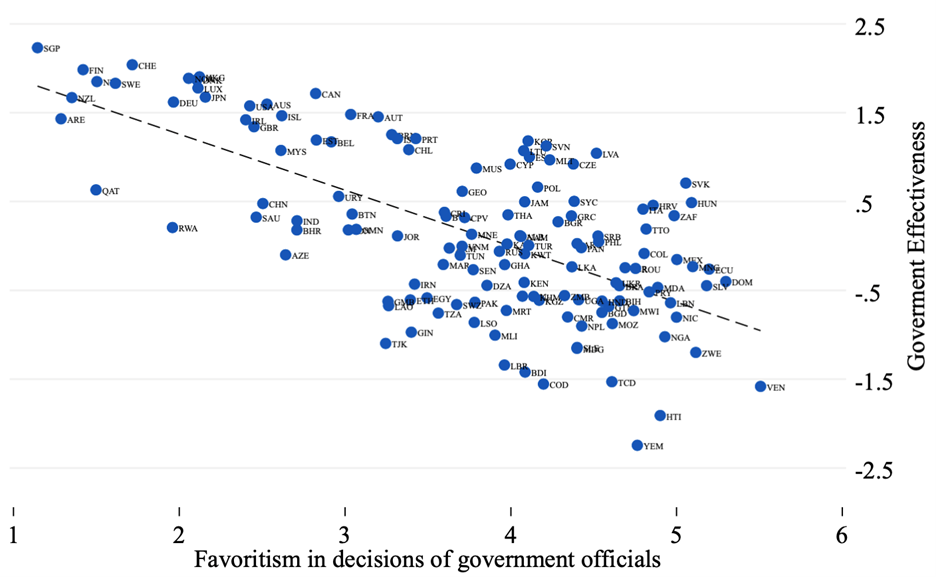

Evidence in economics suggests that the allocation and compensation of public sector workers systematically affect the process of state capacity building (Besley et al. 2022, Best et al. 2022, Bergeron et al. 2022, Fenizia 2022, Colonnelli et al. 2020, Xu et al. 2021, Xu 2018, Dal-Bo et al. 2013). Yet, private incentives and misaligned social norms can distort these elements in modern bureaucracies (Bandiera et al. 2023). For example, even though nepotism is illegal in most bureaucracies, recent public sector perception surveys (Meyer-Sahling 2018) and anecdotal evidence indicate that this form of favouritism is still widespread, especially in developing countries, where family ties are strong, and career civil service systems remain weak. Figure 1 shows, for instance, how citizens’ perception of favouritism by government officials negatively correlates with government effectiveness worldwide; and how developing countries are usually placed on the upper tail of the perception of favouritism.

Figure 1: Perception of favouritism and government effectiveness

Notes: Data from the World Bank governance indicators and GovData360. Favoritism by government officials comes from The Global Competitiveness Report 2017-2018; the index goes from 1 = Never show favoritism to 7=Always show favoritism. The government effectiveness index measures the quality of public services, civil service, policy formulation, policy implementation, and credibility of the government’s commitment to raising these qualities or keeping them high. This index includes 193 countries ranked from -2.5 (least effective) to 2.5 (most effective).

Although there is a significant amount of work documenting the potential costs of allowing family connections to politicians in the public sector (Fafchamps and Labonne 2017, Folke et al. 2017, Gagliarducci and Manacorda 2020, Cruz et al. 2017) and many studies have highlighted the influence of political dynasties in economic development (Dal-Bó et al. 2009, Querubin 2016, Dal-Bó et al. 2017, George 2020), we do not know much about the role of nepotism when other influential groups of individuals exercise it within the public sector, such as non-elected managers and supervisors. This lack of evidence is surprising because in most Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), these individuals still retain a lot of discretion when it comes to public employment outcomes, and they remain only indirectly responsible for these decisions or the consequences of implementing policy in front of citizens and the media.

This unexplored form of "Bureaucratic Nepotism," as I call it, is extremely challenging to detect. One needs to observe not only family connections between public sector workers but also their entire career progression within the public administration. The latter must specify exactly when hirings, promotions, and pay raises occur since this form of favouritism is inherently dependent on the timing of the events, and the asymmetry of power between the relatives involved. For example, the mere presence of two family members in the same institution does not necessarily prove the existence of nepotistic practices. People find romantic partners in the workplace or select into the same institutions at different times for a variety of reasons.

In a recent working paper (Riaño 2023), I address these empirical challenges and document the extent, functioning, and consequences of this form of favouritism using data for an entire modern bureaucracy: the Colombian public sector from 2011 to 2017. To do so, I collect and combine detailed biographical information, employer-employee records, and the mandatory but confidential disclosure of family ties — in the first degree of consanguinity and affinity — of every worker in the administration. This extensive data collection effort, and a new method of family network reconstruction, allow me to recreate not only the entire career paths of more than 1.1 million civil servants but also their extended family networks spanning more than 2.4 million individuals via blood and marriage ties.

How widespread are family connections, and how is their presence related to public sector performance?

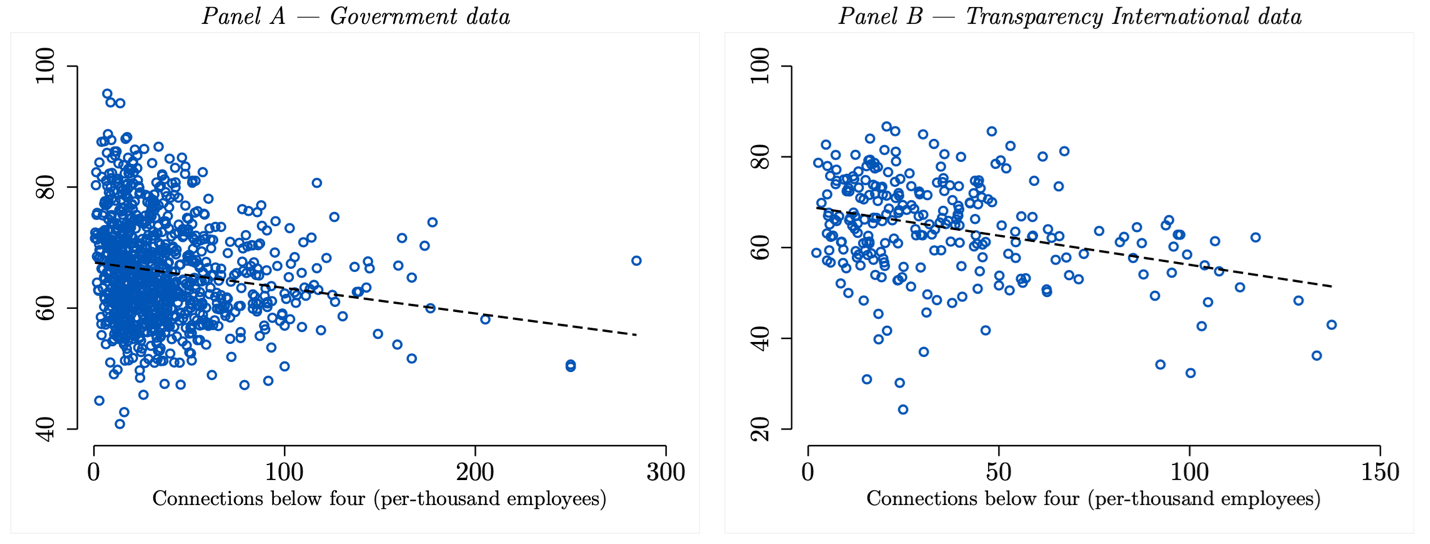

Family connections are pervasive in the Colombian public administration, with 38% of civil servants having a relative in the public sector. Additionally, 18% have a family connection to a manager or supervisor, and 11% work with a family member within the same agency. These connections exist, on average, among close family members, between two and three degrees of consanguinity. However, these close family connections seem to be negatively related to overall measures of institutional performance (see Figure 2), with a one standard deviation increase in close family connections corresponding to a 0.24 standard deviation decrease in agency aggregate performance.

Figure 2: Close family ties and performance at the agency level

Notes: This figure presents the scatter plot and linear fit between the number of family connections below four degrees of consanguinity and the overall performance index (0 to 100) of public sector agencies in 2016 according to government data (Panel A) and the independent assessment from Transparency International (Panel B). The corresponding regressions with further controls are reported in Table 2.

How large are the returns of family ties to public sector managers and supervisors?

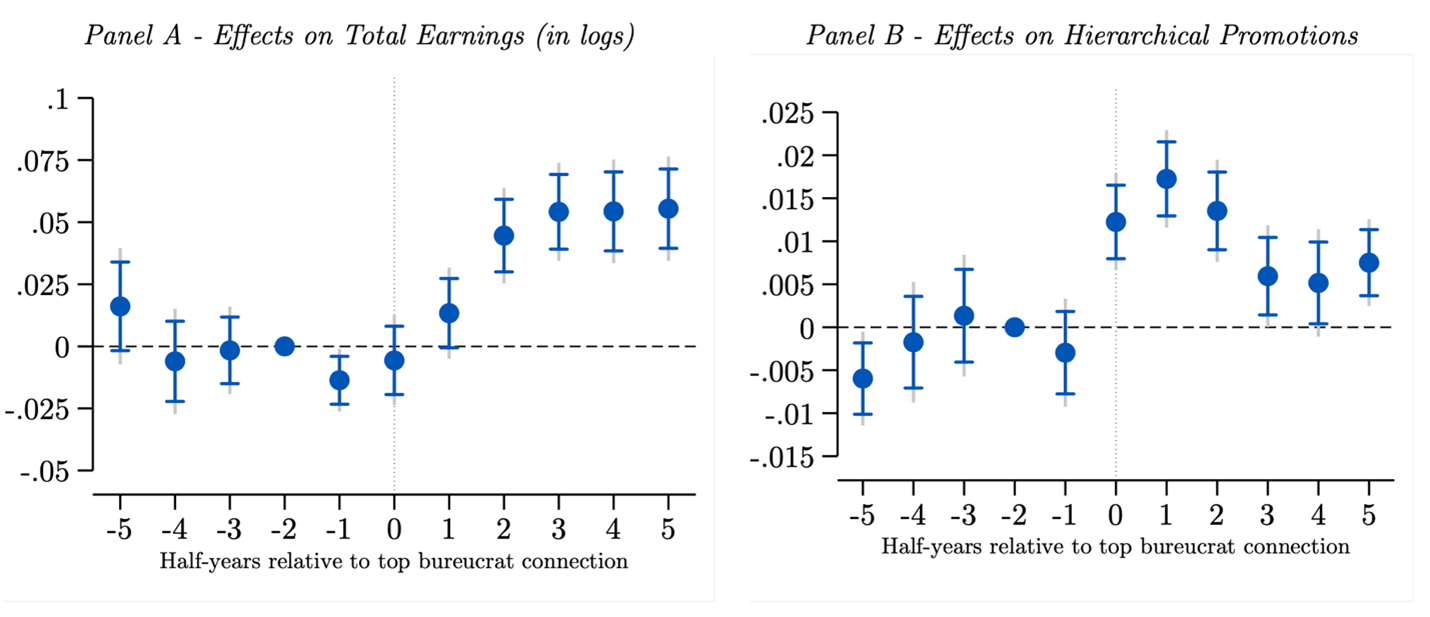

To answer this question, my empirical strategy exploits quasi-experimental variation in family connections generated by the managerial turnover of top non-elected bureaucrats. Specifically, I compare the career progression of workers before and after one of their relatives becomes a top bureaucrat, allowing me to isolate the effects of family ties from other bureaucrat-specific factors that might influence career advancement. My results show that family connections have a significant impact on the career prospects of middle- and lower-tier bureaucrats (see Figure 3), with workers becoming 40% more likely to be hierarchically promoted and receiving a 2% to 5% higher salary when they are connected to a top bureaucrat. These benefits are usually based on temporary promotions. Moreover, they are primarily concentrated among extended family networks that are more difficult for regulatory agencies to identify and not currently audited, such as those 3 to 5 degrees of consanguinity apart.

Figure 3: Event study plotting the effects of having a family connection to a public sector manager or supervisor

Notes: Figure displays the coefficients and 99% and 95% confidence intervals from the event study of ever getting a family connection to a top bureaucrat (i.e., to a public sector manager or advisor) when looking at total earnings and hierarchical promotions as outcomes. Standard errors are clustered at the dyadic family-agency level. The reference period is the year before the first family connection to a top bureaucrat (-2 half-years in the graph). Each figure is based on 6,390,117 panel observations coming from 722,366 bureaucrats and 34,887 connection events to top bureaucrats.

Are these nepotistic returns still consistent with better screening of workers via family networks?

Although the estimation of these nepotistic returns is already illegal according to standard anti-nepotism legislation, a natural question to ask is whether such favouritism is, in fact, detrimental to the allocation and compensation of a more qualified workforce. To answer this question, I build on recent works by Benson et al. (2019) and Voth and Xu (2021) and estimate the differences in pre-promotion characteristics between promoted and passed-over bureaucrats when connected or not to top non-elected bureaucrats. I show that even though public sector managers promote, in general, better-suited individuals, they are also more likely to overlook critical qualifications when promoting family members. On average, promoted workers tend to have more education, public sector experience, and fewer records of misconduct. However, those positive differences disappear or completely flip signs when promotees are related to top non-elected bureaucrats.

Why has anti-nepotism legislation been so ineffective in preventing bureaucratic nepotism?

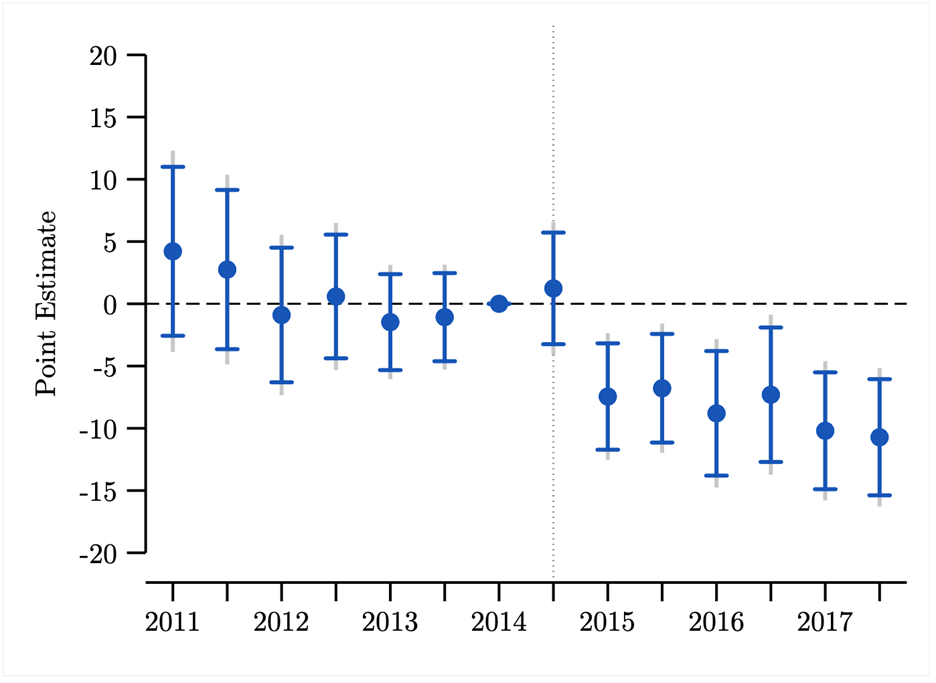

To address this question, I examine the degree to which the enforcement of a new anti-nepotism reform in 2015 – that banned the appointment of family members up to four degrees of consanguinity – could effectively stop the spread of kin favouritism in Colombia. Using an identification strategy exploiting the discontinuity in the set of family connections restricted by this law, I find that even though the reform reduced the number of illegal connections by almost 15% with respect to its sample mean (see Figure 4), this policy change did not improve the quality of the workforce or stop kin favouritism from occurring.

Figure 4: Effects of the 2015 anti-nepotism reform on illegal connections

Notes: The figure displays the coefficients and 99% and 95% confidence intervals from the event study around the introduction of the anti-nepotism legislation in 2015. The coefficient represents the difference in the number of family connections per-ten-thousand employees below four degrees of consanguinity with respect to connections above four for every period in the x-axis.

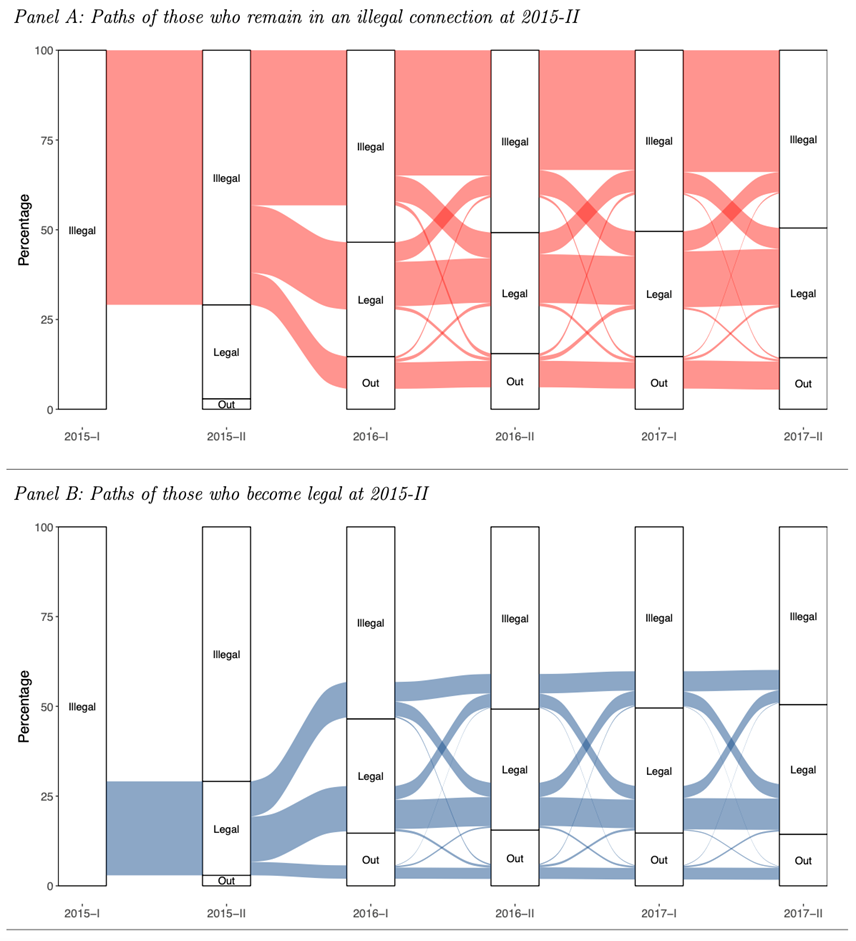

In fact, as I show in Figure 5, 40% of middle-tier and low-tier bureaucrats who were part of illegal connections before the reform kept their same jobs, 30% did not leave the public administration but simply reshuffled posts across public sector agencies, and among those who initially complied with the reform and left the public sector, around 10% returned to be part of nepotistic networks every period. Therefore, the negative selection documented prior to the reform never actually left the public administration. More surprisingly, I find that top bureaucrats strategically responded to this reform by substituting hierarchical promotions for wage increases, which were not explicitly restricted in the anti-nepotism legislation.

Figure 5: Recidivism and reshuffling in the public administration after anti-nepotism policy

Notes: This figure shows the shares and flows over time of middle- and lower-tier bureaucrats who were part of an illegal connection in the first semester of 2015-I. Using this sample, the figure follows bureaucrats over time through three mutually exclusive states: “illegal,” “legal,” or “out.” The first state “illegal” is reached if bureaucrats stay put or become connected to another top bureaucrat at four degrees of consanguinity or less in the next period. In contrast, the “Legal” status is reached when bureaucrats move to another public sector agency where no family connection to a top bureaucrat exists to such a degree. Finally, bureaucrats get to the “Out” state when they leave the public administration by either moving to the private sector or unemployment. Both panels show in hollow bars the fraction (i.e., the stock) of bureaucrats at each state labeled in the column. In colors, the figure presents the flow of bureaucrats from one state to another.

Policy implications

These results have important implications and inform the debate of public sector reforms aimed at stopping the spread of nepotism and other forms of corruption within public administrations. More specifically, my results imply that:

- Automated technologies to detect and audit bureaucratic nepotism may be necessary to enforce anti-nepotism laws effectively. In addition, these investments could improve the quality of the public sector workforce if properly executed.

- When designing anti-nepotism legislation, it is crucial to consider how bureaucrats may strategically respond to the new laws. This includes paying attention to the use of temporary contracts and appointments that may be used to reward, reallocate, or compensate relatives after the anti-nepotism law is enacted.

- The fight against corruption in the public sector has been impeded by an excessive focus on political discretion rather than bureaucratic influence. This emphasis has hindered progress in combating corruption and its detrimental effects on state capacity. A more balanced approach that addresses both forms of discretion is required to make significant strides toward eradicating corruption, especially in LMICs.

Editor's note: This paper was featured in STEG's Working Paper Series.

References

Riaño, J F (2023), “Bureaucratic Nepotism” Available at SSRN or here.

Bandiera, O, R Burgess, E Deserranno, R Morel, I Rasul and M Sulaiman (2023), “Social Incentives, Delivery Agents and the Effectiveness of Development Interventions.” Journal of Political Economy Microeconomics, forthcoming.

Benson, A, D Li and K Shue (2019), “Promotions and the Peter Principle.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(4): 2085-2134.

Bergeron, A, P Bessone, J Kabeya, G Tourek and J Weigel (2022), “Optimal Assignment of Bureaucrats: Evidence from Randomly Assigned Tax Collectors in the DRC”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP1677.

Besley, T J, R Burgess, A Khan and G Xu (2022), “Bureaucracy and Development.” Annual Review of Economics, 14: 397-424.

Best, M C, J Hjort and D Szakonyi (2023), “Individuals and Organizations as Sources of State Effectiveness”, American Economic Review, forthcoming.

Brassiolo, P, R Estrada, G Fajardo, and J Martinez-Correa (2021), “Family Rules: Nepotism in the Mexican Judiciary.” Mimeo.

Colonnelli, E, M Prem and E Teso (2020), “Patronage and Selection in Public Sector Organizations.” American Economic Review, 110(10): 3071-99.

Cruz, C, J Labonne and P Querubín (2017), “Politician Family Networks and Electoral Outcomes: Evidence from the Philippines.” American Economic Review, 107(10): 3006-37.

Dal-Bó, E., Dal-Bó, P., & Snyder, J. (2009). "Political Dynasties." The Review of Economic Studies, 76, 115 – 142.

Dal-Bó, E, F Finan and M A Rossi (2013), “Strengthening State Capabilities: The Role of Financial Incentives in the Call to Public Service.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(3): 1169-1218.

Dal-Bó, E, F Finan, O Folke, T Persson and J Rickne (2017), “Who Becomes A Politician?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(4): 1877-1914.

Fafchamps, M and J Labonne (2017), “Do Politicians’ Relatives Get Better Jobs? Evidence from Municipal Elections.” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 1–33.

Fenizia, A (2022), “Managers and productivity in the public sector.” Econometrica, 90(3): 1063-1084.

Folke, O, T Persson and J Rickne (2017), “Dynastic Political Rents? Economic Benefits to Relatives of Top Politicians.” The Economic Journal, 127(605): F495-F517.

Gagliarducci, S and M Manacorda (2020), “Politics in the Family: Nepotism and the Hiring Decisions of Italian Firms.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 12(2): 67-95.

George, S E (2020), “Like father, like son? The effect of political dynasties on economic development.” Mimeo.

Meyer-Sahling, J H, C Schuster and K S Mikkelsen (2018), “Civil Service Management In Developing Countries: What Works? Evidence From A Survey Of 23,000 Civil Servants In Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, And Latin America (Report).” London: UK Department for International Development (DFID).

Querubin, P (2016), “Family and politics: Dynastic persistence in the Philippines.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 11(2): 151-181.

Voth, J and G Xu (2021), “Discretion and Destruction: Promotions, Performance, and Patronage in the Royal Navy.” Mimeo

Xu, G, M Bertrand and R Burgess (2021), “Organization of the State: Home Assignment and Bureaucrat Performance.” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization.

Xu, G (2018), “The Costs of Patronage: Evidence from the British Empire.” American Economic Review, 108(11): 3170-98.