A property tax campaign in the city of Kananga increased tax compliance and stimulated citizen demand for inclusive and accountable government

Donors and policymakers increasingly support programmes to boost domestic revenue mobilisation in developing countries (Pomeranz and Vila-Belda 2019). The rationale is twofold: armed with tax revenues, governments will be able to provide more public goods – from roads to schools and hospitals – and also fulfil other needed functions, such as contract enforcement (Kaldor 1963, Besley and Persson 2013).

In addition to this direct benefit to the quality of governance, increasing domestic taxation is thought to have an indirect benefit: catalysing citizen participation in politics and, eventually, government accountability (Paler 2013, Prichard 2015). “Bringing small businesses into the tax net can help secure their participation in the political process and improve government accountability,” wrote the IMF in 2011.

Building on past evidence from cross-country comparisons, as well as lab and survey experiments, in a recent study (Weigel 2020) I find support for this indirect ‘participation dividend of taxation’ in the context of a randomised policy experiment in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

The social contract and tax bargaining

The slogan “no taxation without representation” captures an old, powerful idea: taxation lies at the root of the social contract between citizens and the state (Schumpeter 1918). Rulers can try to coerce their subjects to pay, but that usually results in low revenues — people excel at hiding assets in the face of expropriation — and widespread discontent, if not rebellion (Levi 1989). To raise large amounts of tax revenue, governments must give citizens a say in how their hard-earned tax dollars are spent.

Indeed, when expensive European wars brought rulers to the brink of default in the early modern period, many of them began to systematise tax collection (Tilly 1985). Citizens responded to tax appeals by demanding a voice in politics first. Tax bargaining is the process by which citizens and the state negotiated a social contract: citizens agreed to fund the state in exchange for more inclusive and responsive governance, the story goes.

Although cross-country evidence shows a strong positive correlation between tax revenue and political participation, it is not obvious if this relationship is causal, as implied by the IMF. For instance, economic modernisation may increase both participation and taxation. It is also not obvious that citizens would decide to engage more with a state that is trying to tax them. They might prefer to evade quietly or move beyond the state’s reach.

The study: Property tax compliance and political participation in Kananga

A recent property tax campaign in the city of Kananga, the capital of the Kasaï-Central Province in the DRC, provides experimental evidence on the supposed participation dividend of tax collection. In 2016, the Provincial Government of Kasai Central was facing revenue shortfalls due to a recent nationwide splitting of provincial borders that cut several lucrative territories from its tax remit. Consistent with international best practices concerning revenue sources for local governments, it turned to property tax, seeking to extend the tax net throughout the city of Kananga.

Importantly, the Provincial Government of Kasai Central chose to randomise the rollout of its 2016 door-to-door property tax collection campaign, the first of its kind in Kananga. Thus, 253 of the 431 neighbourhoods in Kananga were assigned to the ‘treatment’, in which tax collectors went door to door registering households as potential taxpayers and making in-person tax appeals. In the remaining 178 ‘control’ neighbourhoods, citizens were expected to pay at the Tax Ministry themselves in 2016, as was the status quo in the DRC’s declarative tax system, and were scheduled to receive visits from tax collectors the following year.

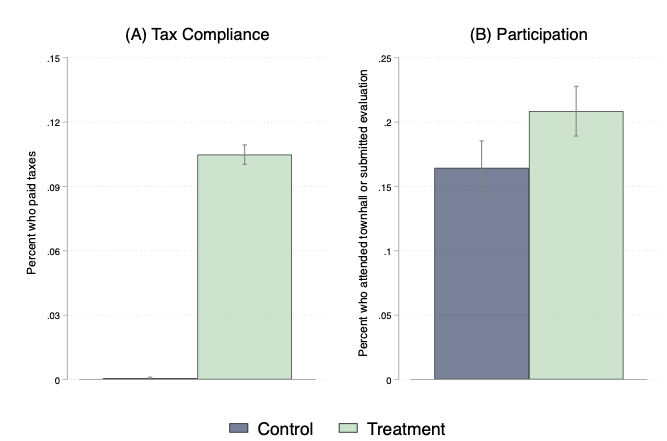

Door-to-door collection increased property tax compliance from 0.1% in control neighbourhoods to 11.6% in treatment neighbourhoods (Figure 1, panel A). Although the majority of citizens still avoided paying the tax, property tax compliance reached levels on par with national capitals in more affluent African countries. Moreover, this was the first year the great majority of citizens had been solicited to pay the property tax, and the government anticipated progressively higher compliance in the future.

Figure 1 Effects of the tax campaign on tax compliance and political participation

Notes: This figure shows average property tax compliance (Panel A) and political participation (Panel B) in treatment and control neighbourhoods. Tax compliance is measured using administrative tax data. Participation is measured as attendance at a townhall meeting or submission of a government evaluation.

Findings: The participation dividend of taxation

Did citizens whose properties were registered by the tax authorities and who were asked to pay the property tax for the first-time demand more of a voice in politics? The randomised rollout of the tax campaign affords a rigorous answer to this question because all other factors that might influence participation — wealth, education, political affiliation, ethnicity, etc. — were, by design, similar across treatment and control neighbourhoods. If we observe a difference in participation across the treatment groups, it could only be attributable to the tax campaign.

Consistent with the idea of a participation dividend of taxation, citizens in treated neighbourhoods were about five percentage points more likely to turn up at townhall meetings hosted by the provincial government (Figure 2) or to submit anonymous evaluations of the government to a locked drop box downtown (Figure 1, panel B).

Figure 2 Participants at a townhall meeting in Kananga, 30 January 2017

Notes: This photograph was taken at the first of five townhall meetings hosted by the provincial government. Citizens in treatment and control neighbourhoods received invitations at equal rates and chose whether or not to attend.

On average, citizens spent the equivalent of their household’s daily income to participate in these ways, revealing the importance they placed on demanding a voice in the provincial government. Both types of political participation occurred on average six to eight months after the tax campaign, and the magnitude of the treatment effect shows no sign of decreasing over time.

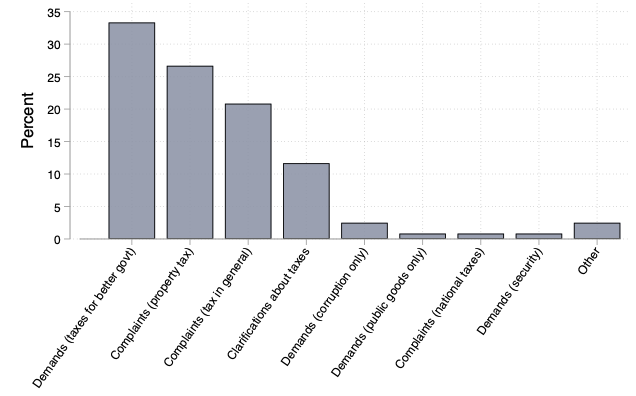

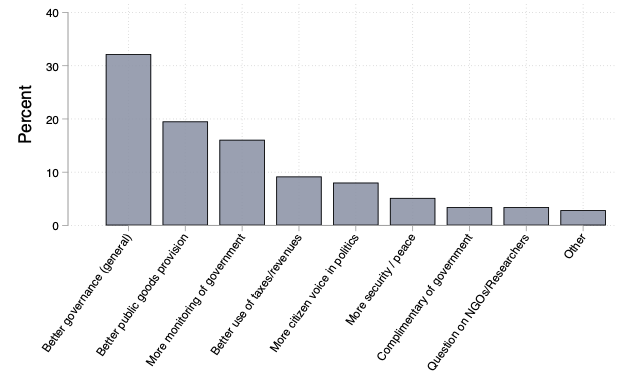

Citizens who participated in these ways demanded more inclusive politics and better public goods provision. For example, Figures 3 and 4 summarise the distribution of topics raised by citizens who spoke at townhall meetings and who wrote suggestions on their evaluation forms, respectively. “Erosion threatens our neighbourhoods, and the government does nothing,” said one person, “so why should we pay?” Citizens appear to have participated to engage in tax bargaining — threatening non-compliance with taxes if the government did not reciprocate in the form of more responsive and participatory governance.

Figure 3 Topics of townhall participants’ comments

Notes: This figure summarises the distribution of topics raised by citizens during townhall meetings. Demands (taxes for better govt) include comments (i) directly discussing how provincial tax revenues would be spent, or (ii) explicitly linking provincial taxation with demands about public goods, corruption, or citizen monitoring. This category thus captures the idea of a legitimate exchange of taxes for better governance that is the essence of tax bargaining. If citizens brought up other governance failures without mentioning taxation in the same comment, then this is coded in a different category, for example, “Demands (corruption only)” or “Demands (public goods only).”

Figure 4 Topics of written-in comments on government evaluation forms

Notes: This figure summarises the distribution of topics on submitted evaluations, in which citizens wrote in optional comments or suggestions at the bottom of the form.

Implications: Fostering inclusive and accountable governance

The 2016 property tax campaign in Kananga thus provides experimental evidence that tax collection stimulates citizen participation and demand for accountable governance, even in settings with weak states and autocratic regimes. Policies and programmes that help expand government capacity to collect taxes systematically from a broad base can thus have both direct benefits — by increasing revenue for public goods provision — and indirect benefits — by catalysing participation — on the quality of governance.

However, it is important to think carefully about the conditions under which these findings are likely to generalise in other contexts. Two aspects are worth highlighting. First, property taxes, like most direct taxes, are very salient to citizens and may thus generate a larger political response than indirect taxes that manifest in higher prices. If promoting participation is an explicit goal of tax capacity programmes, policymakers should consider what tax instruments are available and how salient they are to citizens. Second, the 2016 property tax campaign in Kananga involved systematic, non-coercive tax collection. If tax collectors, instead, differentially target minorities or other groups that lack a voice in politics (Meagher 2018), the participation dividend of taxation may prove more elusive.

References

Besley, T, and T Persson (2013), “Taxation and Development”, Handbook of Public Economics, Vol. 5., Amsterdam: Elsevier.

IMF (2011), Revenue Mobilization in Developing Countries, IMF Policy Report.

Kaldor, N (1963), “Will Underdeveloped Countries Learn to Tax?”, Foreign Affairs, 41, 410–419.

Levi, M (1989), Of Rule and Revenue, University of California Press.

Meagher, K (2018), “Taxing Times: Taxation, Divided Societies and the Informal Economy in Northern Nigeria”, Journal of Development Studies, 54, 1–17.

Paler, L (2013), “Keeping the Public Purse: An Experiment in Windfalls, Taxes, and the Incentives to Restrain Government”, American Political Science Review, 107, 706–725.

Pomeranz, D and J Vila-Belda (2019), “Taking State-Capacity Research to the Field: Insights from Collaborations with Tax Authorities”, Annual Review of Economics, 11, 755–781.

Prichard, W (2015), Taxation, Responsiveness and Accountability in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Dynamics of Tax Bargaining, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schumpeter, J A (1918), “The Crisis of the Tax State”, International Economic Papers, 4, 5–38.

Tilly, C (1985), “War Making and State Making as Organized Crime”, in P Evans, D Rueschemeyer, and T Skocpol (eds), Bringing the State Back, Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

Weigel, J (2020), “The Participation Dividend of Taxation: How Citizens in Congo Engage More with the State when it Tries to Tax Them”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135 (4).