A one-off demonetisation led to a shift to electronic payments, which in turn increased tax compliance

Policymakers and academics alike have long argued that electronic payments may be easier to tax than cash. Unlike cash, electronic transactions are processed by financial intermediaries, creating a (metaphorical) paper trail which tax authorities can use to assess tax liabilities (Rogoff 2016, OECD 2017, Awasthi and Engelschalk 2018). If true, this is excellent news for developing countries, where transactions are increasingly electronic and low tax compliance severely constrains government revenues (Pomeranz and Vila-Belda 2019). The World Bank estimates that between 2014 and 2017, the share of adults using electronic payments in the developing world increased by over a third (Demirguc-Kunt et al. 2018). The COVID-19 crisis accelerated this trend as consumers and firms moved away from cash.

However, there are reasons to doubt that the shift to electronic payments will increase tax compliance. Fiscal authorities having more information on tax liabilities does not automatically lead to more tax compliance. Existing evidence has shown that governments do not always have the capacity to use third-party information effectively (Almunia et al 2019), and that firms may react strategically to keep their tax liabilities low (Carillo et al 2017). Whether electronic payments increase tax revenues is thus an empirical question, and empirical evidence on the subject is scarce.

Demonetisation in India increased electronic transactions

In recent work with Satadru Das (Das et al. 2022), we provide new evidence on the effect of electronic payments on tax compliance in the context of West Bengal, India. To do so, we use the fact that India’s one-off demonetisation policy led to a dramatic change in the payment technology used by consumers and firms. On 8 November 2016, the government of India declared 86% of the existing currency in circulation illegal tender (Lahiri 2020). Printing constraints prevented the immediate replacement of old currency with new notes, leading to a sharp decrease in cash in circulation and a marked increase in the use of electronic means of payment to conduct transactions. The top-right panel of Figure 1 shows a sharp increase in the number of electronic transactions in West Bengal during the demonetisation period (the last quarter of 2016 and the first quarter of 2017), corresponding with a 500% increase once we control for economic activity.

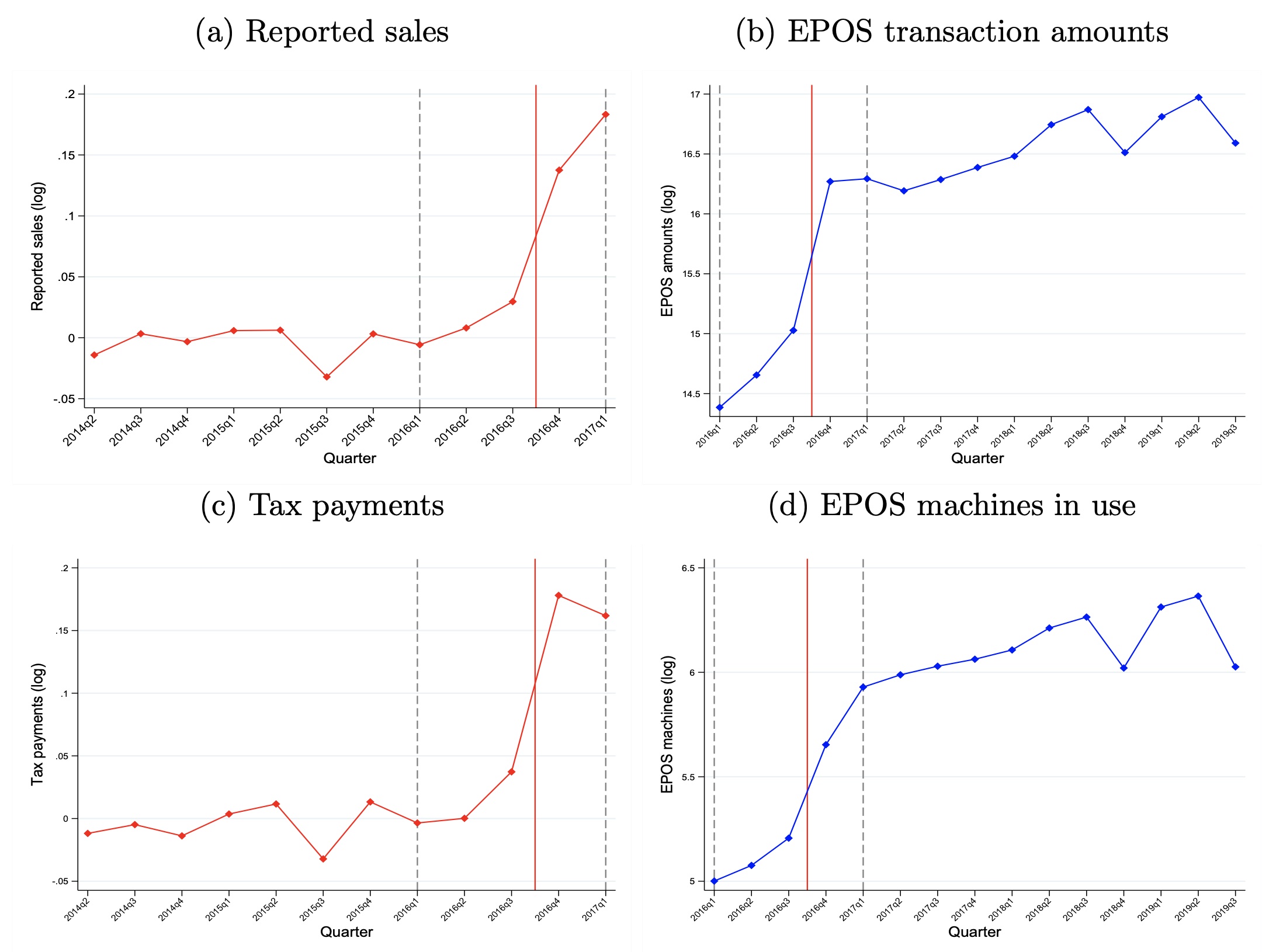

Figure 1 Evaluation of tax returns and electronic transaction variables over time

Note: The graphs plot the evolution of tax returns and electronic transaction variables over time for the period between 2014-2017. Panels on the left (in red) plot the evolution of tax returns, with the top left showing log reported sales, and the bottom left showing log tax payments. These variables are residualised by taking quarter-of-year times district fixed effects. Panels on the right (in blue) plot the evolution of electronic payments, with the top right showing log transaction amounts, and bottom right showing the log number of electronic payments machines in use. Each point is an average across firms for each quarter. See Das et al 2022 for a description of the variables and data sources.

Using administrative data on quarterly tax returns for all firms paying value addded tax (VAT) in West Bengal, we start by looking at trends in firms’ tax behaviour during the demonetisation period. The left-hand panels of Figure 1 show an increase in both average sales reported to the tax authorities and average taxes paid over time during the demonetisation period (this corresponds with a 10-11% increase upon controlling for economic activity). This rise is a priori surprising given the negative effects of demonetisation on the Indian economy (by now well established, e.g. Chodorow-Reich et al 2020) which should, if anything, have led to a decrease in tax payments.

To investigate whether the trend in Figure 1 can be explained by the rise in electronic payments, we use local-level data on electronic payments from the Reserve Bank of India and apply an identification strategy developed by other papers studying the economic effects of demonetisation (see Crouzet et al 2019, Chodorow-Reich et al 2020). This strategy assumes that since newly printed currency notes were distributed through local bank branches working with the Reserve Bank of India, different areas in India had access to the new notes at different speeds, depending on their proximity to these bank branches. This allows us to utilise the local deposit share of these bank branches as an instrument for local growth in electronic payments. We control flexibly for the effect of demonetisation on real economic activity, using different proxies for local activity so our estimates capture local compliance effects and not an increase in firms’ true sales.

Electronic payments seem to increase tax compliance

We find that the shift to electronic means of payments during demonetisation did induce firms to report higher sales to the tax authorities: a 10% increase in electronic payments in a local area increased average reported sales by 0.3%. Taxes paid also rose by roughly the same amount. There is a small effect on the probability that firms pay positive amounts of tax, but these estimates are less precise. Overall, our evidence is in line with the idea that electronic payments increase tax compliance. Given the sizeable increase in electronic payments during demonetisation, our estimates imply that roughly half of the increase in reported sales and taxes paid (as seen in the left-hand panels of Figure 1) can be explained by the increase in electronic payments.

Data limitations imply that we can only look at effects on firms already registered with the tax authorities prior to demonetisation, and not at the entry of new firms into the tax net. However, the bottom-right panel of Figure 1 speaks indirectly to this question: we see a large increase in the number of electronic payment machines used by firms over time. This suggests that many firms started accepting electronic forms of payment during demonetisation, which may have led them to also start filing tax returns when they realised it made them more visible to the tax authorities.

How long did this effect last? Unfortunately, our administrative tax data stop in March 2017, four months after the start of demonetisation, so we cannot consider medium-run effects. But our data on electronic payments show that the increase observed during demonetisation lasted for at least three years afterwards. It is thus possible that the compliance effects outlived the negative effects on economic activity, which seemed to dissipate after a few months (Chodorow-Reich et al 2020).

References

Almunia, M, J Hjort, J Knebelmann, and L Tian (2021), “Strategic or Confused Firms? Evidence from ‘Missing’ Transactions in Uganda”, NBER Working Paper No. 29059.

Awasthi, R, and M Engelschalk (2018), “Taxation and the shadow economy: how the tax system can stimulate and enforce the formalization of business activities”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8391.

Carrillo, P, D Pomeranz, and M Singhal (2017), “Dodging the taxman: Firm misreporting and limits to tax enforcement”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9(2): 144-64.

Chodorow-Reich, G, G Gopinath, P Mishra, and A Narayanan (2020), “Cash and the economy: Evidence from India’s demonetization”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(1): 57-103.

Crouzet, N, A Gupta, and F Mezzanotti (2019), “Shocks and technology adoption: Evidence from electronic payment systems”, Working Paper, Northwestern University.

Das, S, L Gadenne, T Nandi, and R Warwick (2022), “Does going cashless make you tax-rich? Evidence from India’s demonetization experiment”, Institute for Fiscal Studies Working Paper W22/03.

Demirguc-Kunt, A, L Klapper, D Singer, and S Ansar (2018), The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution, World Bank Publications.

Lahiri, A (2020), “The Great Indian Demonetization”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 34(1):55-74.

OECD (2017), Shining light on the shadow economy: Opportunities and threats.

Pomeranz, D, and J Vila-Belda (2019), “Taking state-capacity research to the field: Insights from collaborations with tax authorities”, Annual Review of Economics 11: 755-781.

Rogoff, K (2017), The curse of cash, Princeton University Press.