While China’s bureaucracy and institutions allow large-scale policy experimentation, incentives in complex political environments can inhibit policy learning

Determining which policies to implement and how to implement them is an essential government task (Hayek 1978, North et al. 1990). Policy learning is challenging, as policy effectiveness often hinges on the nature of the policy, its implementation, the degree of tailoring to local conditions, and the efforts and incentives of local politicians to make the policy work.

Many governments have explicitly or implicitly engaged in various forms of policy experimentation in order to resolve policy uncertainty and facilitate policy learning (Roland 2000, Mukand and Rodrik 2005). Sophisticated policy experimentation has ranged from sequences of trials and errors to rigorous randomised controlled trials in sub-regions of a country.

Examining policy experimentation in China

In a recent paper (Wang and Yang 2021), we analyse a large-scale policy experimentation in China since the 1980s, where the government has systematically tried out different policies across regions and often over multiple waves before deciding whether to roll out the policies to the entire nation.

China provides a valuable study context for two reasons.

- The systematic policy experimentation in China is unparalleled in terms of its depth, breadth, and duration.

- Scholars have argued that policy experimentation was a critical mechanism leading to China’s economic rise over the past four decades (Rawski 1995, Cao et al. 1999, Roland 2000, Qian 2002).

Even so, surprisingly little is understood about the characteristics of such policy experimentation, or how the structure of experimentation may affect policy learning and policy outcomes.

How are policy experiments evaluated for national expansion?

We focus on two characteristics of policy experimentation that may determine whether it provides informative and accurate signals on general policy effectiveness. First, to the extent that policy effects are often heterogeneous across localities, representative selection of experimentation sites is critical to ensure unbiased learning of the policy’s average effects. Second, to the extent that the efforts of key actors (such as local politicians) can play important roles in shaping policy outcomes, experiments that induce excessive efforts through local political incentives can result in exaggerated signals of policy effectiveness.

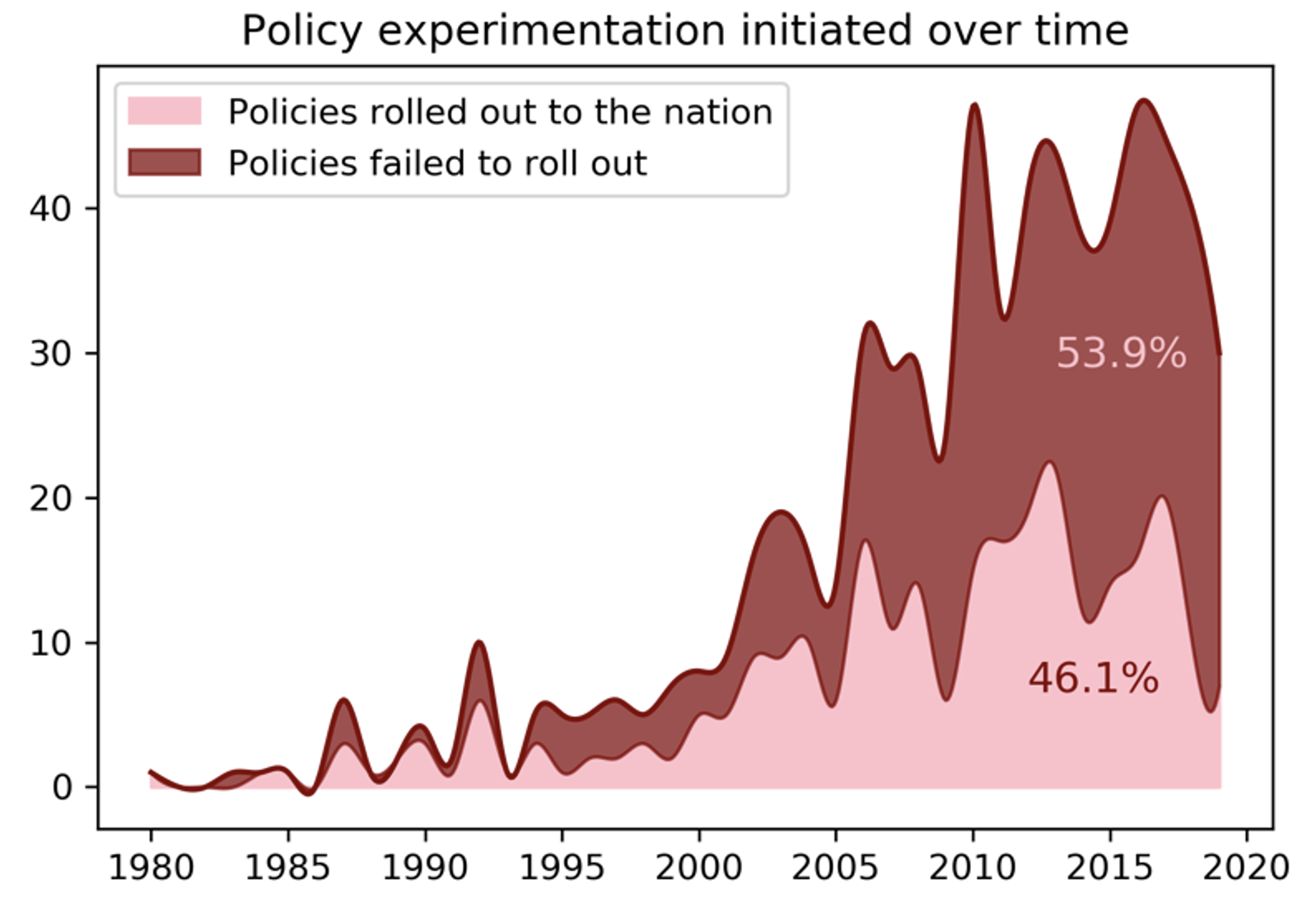

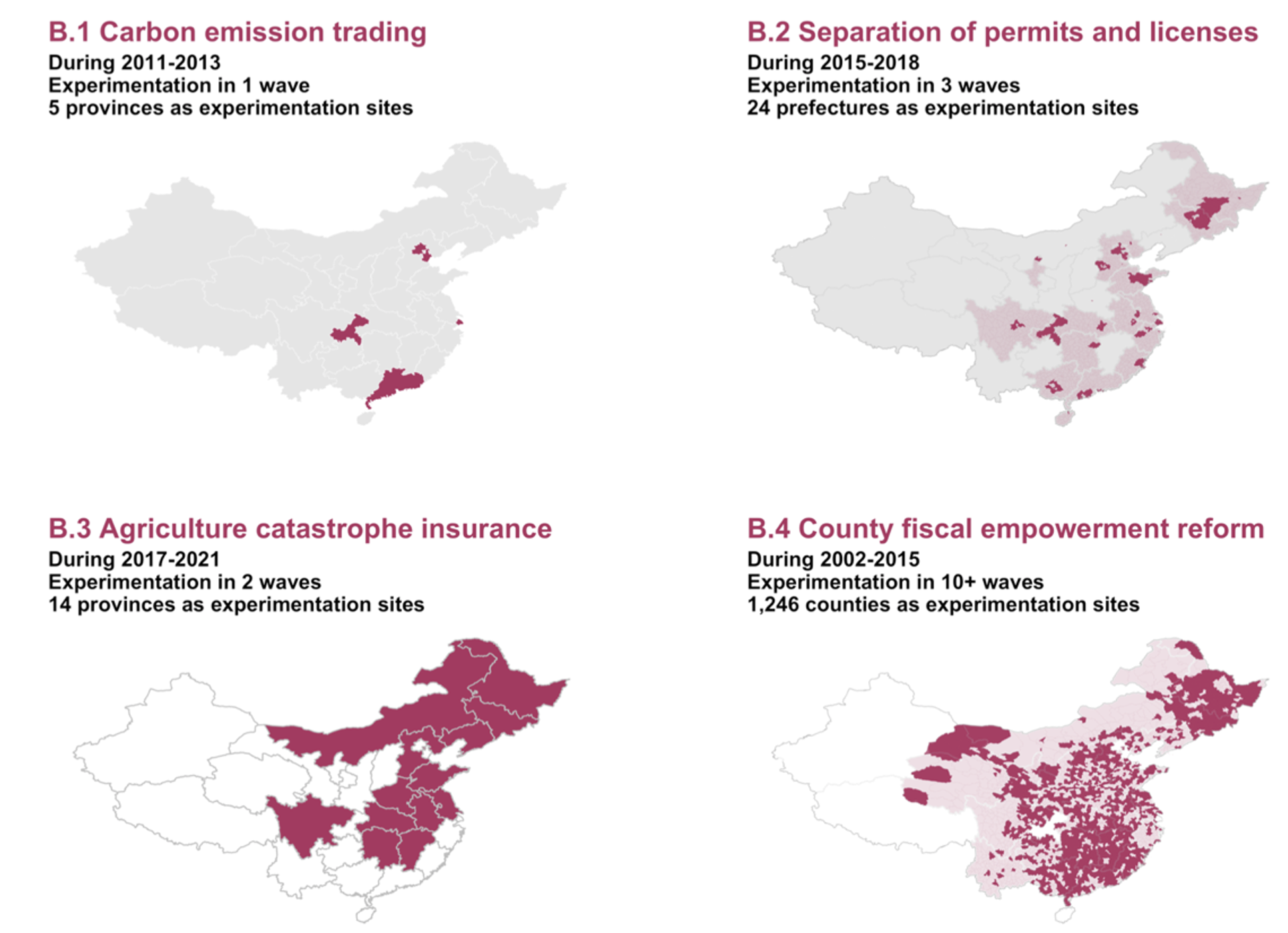

We collect 19,812 government documents on policy experimentation in China between 1980 and 2020 and construct a database of 633 policy experiments initiated by 98 central ministries and commissions. As shown in Figure 1, 46.1% of the assessed policy experiments eventually became national policies, while 53.9% failed. Figure 2 presents four specific examples: two experiments that eventually lead to the introduction of new national policies, and two that did not.

Figure 1 Number of policy experiments initiated over time

Notes: The share of successful experiments that eventually rolled out to the entire country is indicated by the area shaded in pink; the share of unsuccessful policies that failed to roll out to the entire country is indicated by the area shaded in red.

Figure 2 Spatial distribution of policy experimentation in China

Notes: Panels B.1 and B.2 show two policies that eventually rolled out to the entire country. The regions shaded in grey indicate parts of the country that eventually received the policy. Panels B.3 and B.4 show two policies that did not eventually roll out. The experimentation sites are marked in red, and the corresponding provinces are marked in pink.

We document three primary results:

1. Local political incentives shape where experimentation occurs

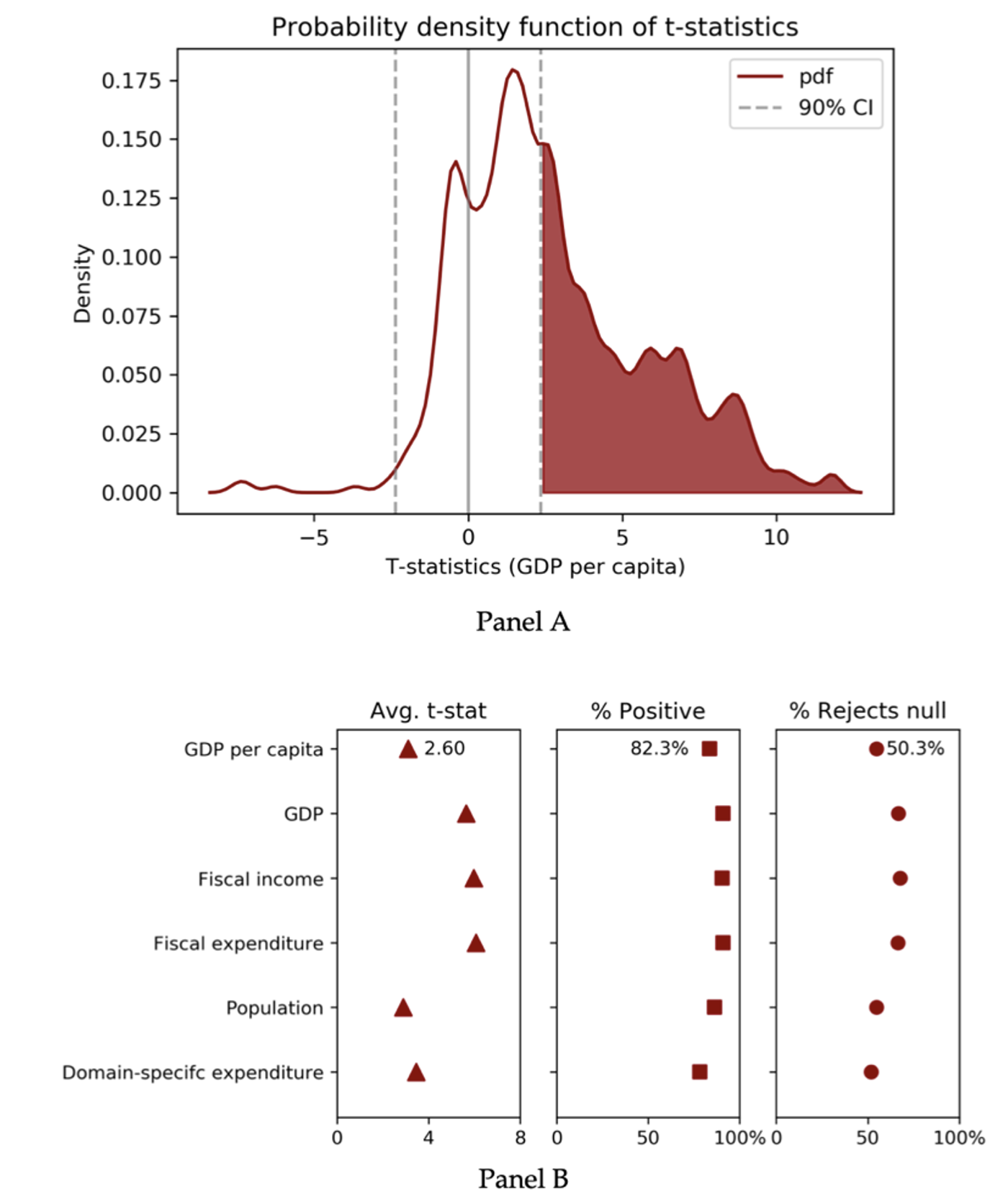

Policy experimentation sites are substantially positively selected in terms of a locality’s level of economic development. As shown in Figure 3, comparing the pre-experimentation characteristics of the locations that are selected as test sites to those that are not, we observe that more than 80% of the experiments were conducted in sites that are positively selected in terms of local economic conditions. Such deviation from representativeness cannot be fully justified by various optimal experimentation considerations. Rather, we find that nearly half of the observed positive selection can be accounted for by misaligned incentives across political hierarchies. Specifically, the level of promotion incentives faced by local politicians (which are greater for politicians who are sufficiently far away from retirement) shape their participation in the experiments, and political patronage affects how ministers choose experimentation sites.

Figure 3 Descriptive facts on the representative test

Notes: Panel A plots the t-statistics distribution from the representativeness test, calculated based on GDP per capita, to serve as an example. Panel B extends the list to more socio-economic characteristics, and reported the mean of t-statistics, the percentage of policies with t-stat> 0, and the percentage of t-tests where we can reject the null hypothesis H0: Y(0) = Y(1) in three sub-panels, respectively. To calculate the t-statistics, we compare the average pre-experimentation characteristics between those jurisdictions chosen as experimentation sites, and their peers at the same hierarchical level that were not chosen as experimentation sites within each test. The grey vertical lines in panel A represent the average critical value at 90% confidence level among all t-tests.

2. Political leaders temporarily invest resources for experiments to succeed

We find that experimental situation during policy experimentation is unrepresentative: local politicians exert strategic efforts and allocate more resources during experimentation. For example, local governments participating in experimentation allocate significantly more fiscal funds in the domains relevant to the policy on trial, and this is particularly the case among local politicians with high promotion incentives. Importantly, such additional efforts and resources may exaggerate general policy effectiveness since these patterns are no longer observed when the policy eventually rolls out to the rest of the country.

3. Central government evaluations miss local political bias

We find that positive sample selection and unrepresentative experimental situation are not fully accounted for when the central government evaluates experimentation outcomes, which would bias policy learning and national policies originated from these experiments. When experimentation sites experienced exogenous positive shocks in fiscal resources (due to unexpected land revenue windfalls during the experimentation) or political incentives (due to local politician turnover occurring during the experimentation), the policies on trial are significantly more likely to be rolled out as national policies despite the fact that the innate effectiveness of these policies is orthogonal to those shocks.

Furthermore, we find that evaluations of experimentation outcomes in the presence of positive sample selection and non-representative experimental situation can influence national policy outcomes. When the trial policies are rolled out to the entire country, localities benefit substantially more from the policies if they share similar socioeconomic conditions or comparable bureaucratic incentives with the corresponding experimentation sites. This could systematically bias the effectiveness of reforms in China and generate distributional consequences across regions.

The policy trade-offs of incentivising experimentation

Taken together, these results highlight that China’s remarkable system of policy experimentation, as with any other undertaking in policy learning at this scale, takes place in complex political and institutional contexts. On the one hand, certain institutional and bureaucratic conditions may serve as the engine to coordinate experimentation, motivate politicians’ participation, and stimulate local policy innovations. Experimentation thus, can help circumvent political and bureaucratic frictions that may prevent reform and policy adoption. On the other hand, as our results suggest, the very same institutional and bureaucratic contexts also imply the presence of factors that could result in deviation from representativeness in both sample selection and experimental situation. If these characteristics of the policy experiments are not sufficiently accounted for, policy learning can be biased, and national policy outcomes may be affected.

Among its important implications, this study offers insights into the fundamental trade-off facing a central government: structuring political incentives to stimulate politicians’ effort to improve policy outcomes, while making sure that such incentives are not exaggerated during the experimentation phase so that policy learning remains unbiased. Solutions that improve mechanism design might enhance the efficiency of policy learning and, likewise, could be of valuable policy relevance and importance.

References

Cao, Y, Y Qian and B R Weingast (1999), “From federalism, Chinese style to privatization, Chinese style”, Economics of Transition 7(1): 103–131.

Hayek, F A (1978), Law, legislation and liberty, Volume 1: Rules and order, University of Chicago Press.

Mukand, S W and D Rodrik (2005), “In search of the holy grail: policy convergence, experimentation, and economic performance”, American Economic Review 95(1): 374–383.

North, D C et al. (1990), Institutions, institutional change and economic performance, Cambridge University Press.

Qian, Y (2002), “How reform worked in China”.

Rawski, T G (1995), “Implications of China’s reform experience”, China Q, p. 1150.

Roland, G (2000), Transition and economics: Politics, markets, and firms, MIT Press.

Wang, S and D Yang (2021), “Policy Experimentation in China: The Political Economy of Policy Learning”, NBER Working Paper 29402.