In an era of deglobalisation, developing countries need more equality within their borders

Many of the success stories of economic development in the past century coincided with growth in exports and trade surpluses, especially in East Asia (Stiglitz 1996). Advances in technology, however, threaten the comparative advantage offered by cheap labour. Moreover, protectionism is now on the rise in advanced economies, imperilling the relevance of the export-led model. This observation has led policymakers to ask: What is the pathway to development in a world with less international integration?

Intuitively, the answer seems to be that developing countries need to rely more on themselves. This path seems more attainable for ‘large’ countries such as India. For example, even if India traded less with other countries, it could still rely on its own market; there could be a lot of trade, but trade would be internal rather than external. However, ‘small’ countries may not have such an option.

This simple intuition raises several questions: What does ‘large’ mean? Is size defined in terms of population, income or geographic area? What is the mechanism through which size leads to development? How ‘large’ (as defined by an appropriate metric) does a country need to be to break into development? And what are the options available to countries that do not make the cut based on their size? In our paper, we try to answer these questions by formalising the above intuition within an economic framework that emphasises the role of demand-side constraints in national development (Goldberg and T Reed 2020).

We define ‘development’ as sustained poverty reduction, measured as a continuous decline in the share of the population living on less than $1.90 PPP per day in 2011 US dollars, over a five-year period. While many indicators summarise a country's progress, poverty reduction is arguably the best indicator that a country is on track to becoming what could be called an advanced economy. Poverty elimination is the first of World Bank's Twin Goals and the first of United Nation's Sustainable Development Goals.

Our focus on the transition between two dichotomous stages of development, one with extreme poverty and one without, follows in the tradition of W. Arthur Lewis’ work (Lewis 1953,1954) and its formalisation by Murphy et al. (1989). In this framework, the economy has two alternative production technologies: one with constant returns to scale and another with increasing returns to scale. Development takes place when firms pay the fixed setup costs of adopting the increasing returns technology, which causes labour productivity to rise. The main implication of this framework is that a minimum efficient scale – a threshold market size – is required to achieve development (if there is not enough demand, a firm adopting the increasing returns technology will not break even).1

Deriving the threshold market size

One way to achieve minimum efficient scale is through access to international markets (Helpman and Krugman 1985). In principle, however, a large enough domestic market could also allow firms using the increasing returns technology to break even. The specific mechanism involves an initial positive wealth shock, from either agricultural productivity or exports. Societies develop faster when this new wealth is distributed more equitably across the population, and the resulting consumption by the middle class is large enough to achieve the minimum efficient scale. These ideas imply that the threshold market size could be achieved through various combinations of: (i) a large population, (ii) an equitable distribution of income, (iii) a large international market.

To implement this framework empirically and derive the threshold market size, we draw on the industrial organisation literature; specifically on Bresnahan and Reiss (1991), who develop a method to estimate entry thresholds based on the profit functions of firms facing increasing returns and entering imperfectly competitive markets.

We model market size as a function of observables. The size of a given country's integrated international market is calculated by summing the population and income of all other countries, where those countries are weighted by the number of economic integration provisions a country has signed with them. The size of the domestic market is measured as a function of the income distribution, i.e. by the share of the population in the global middle class, defined based on Kharas (2017) to include those living on $11–110 PPP per day in 2011 US dollars. The use of an absolute, rather than relative, definition for the middle class reflects the assumption that the increasing returns technology is the same across countries. The empirical model also accounts for other factors that have been shown to impact development, most important of which are geography and institutions which affect firms’ fixed costs of market entry. Setting the size of the integrated international market to zero in a counterfactual scenario allows us to isolate the effect of domestic market size alone on sustained poverty reduction. This exercise quantifies the hope for development in a less globally integrated economy.

International integration and middle class are key

We estimate the threshold market size for sustained poverty reduction to be 328 million people, if the purchasing power of these people is below that of the global middle class. This implies that if threshold market size were based on raw population alone, only three countries in the world (China, India and the US) would be large enough to achieve poverty reduction without international integration and without a middle class.

Of course, in our framework, threshold market size depends not only on raw population, but also on international integration and the size of the middle class. A small country that is internationally integrated may effectively have access to a much larger market. Similarly, a small country with a large fraction of its population in the global middle class may have high enough consumption to support development. Our estimates have three main implications:

- International integration is important, especially when a country integrates with richer countries. To understand the implications of our estimates, consider a hypothetical situation concerning Afghanistan, with a population of approximately 35 million. Suppose Afghanistan contemplates integrating with one of its neighbours; either Pakistan, with population of 200 million, or Iran, with population of 80 million. According to our estimates, opening up to an integrated market of the same population adds the equivalent of 160,000 people to average market size. The multiple of this would be greater if the country integrated with Pakistan. However, income per capita is more important than population size. Joining a market with the same relative income per capita, is equivalent to 20 million people on average in our sample. Pakistan, which has a three times greater income per capita than Afghanistan would be worth an additional 60 million people. However, Iran has income per capita 10 times larger than Afghanistan, and so integration would yield the equivalent of 200 million more people. In this example, Iran is a much more valuable market when one accounts for population and income. Though there are gains to having a large market in terms of population, the main incremental value comes from trading partners' purchasing power. This suggests that so-called ‘South-South’ integration between countries of similar incomes will be less valuable than ‘North-South’ integration between countries of different incomes.

- The middle class share also has a positive and significant effect on sustained poverty reduction. For the average country in our sample, increasing the share of the population in the global middle class by 10% is equivalent to increasing population by 54 million people.

- In a scenario in which the size of the integrated international market is set to zero, as of 2011–2015, the average resident of a low and lower-middle income country does not live in a market large enough to experience sustained poverty reduction. The primary reason for this is that the middle class in these countries is not yet large enough.

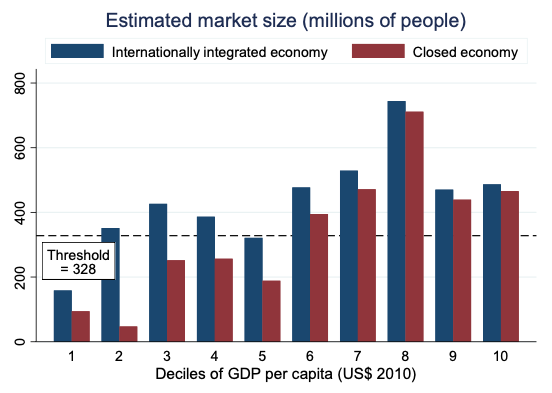

Figure 1 Average market size by income

Figure 1 summarises this insight. It reports estimated market size, averaged over deciles of GDP per capita, using only data from 2011–2015 and weighting observations by population. The blue set of columns correspond to the open economy (at current levels of integration). The red columns show a market size determined only by population and the size of the middle class. Notably, in this closed economy scenario, it is not until the sixth decile of GDP per capita (which corresponds to $2,417) that the market becomes large enough to meet the estimated threshold of 328 million people. The figure once again demonstrates the importance of international integration. In all except the first and fifth deciles, the open economy market size is, on average, greater than the threshold. This suggests that, if international integration remains as in the past, most countries should be able to achieve sustained poverty reduction. The average market size of the open economy, however, does not go far above the threshold.

Amidst deglobalisation, developing countries need more equality within their borders

Our results suggest that international integration has provided a pathway for poor countries to eliminate poverty in the past. If international integration becomes less tenable in the future, to eliminate poverty, policymakers in poor countries would need to focus on equalising the distribution of income, for instance through taxation or (as suggested by the model underlying this paper's analysis) redistribution of equity shares to the poor in order to create a middle class that is large enough to foster development. For countries with small populations, such equalisation is disproportionately important.

References

Banerjee, A V and E Duflo (2005), “Growth theory through the lens of development economics”, Handbook of Economic Growth, 1, 473-552.

Bresnahan, T F and P C Reiss (1991), “Entry and competition in concentrated markets”, Journal of Political Economy, 99(5), 977-1009.

Goldberg, P K and T Reed (2020), “Income Distribution, International Integration and Sustained Poverty Reduction”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9342.

Helpman, E and P R Krugman (1985), Market structure and foreign trade: Increasing returns, imperfect competition, and the international economy, MIT press.

Kharas, Homi (2017), “The unprecedented expansion of the global middle class: An update”.

Lewis, W A (1953), Report on the Industrialization of the Gold Coast, Accra: Government Printing Office of the Gold Coast.

Lewis, W A (1954), “Economic development with unlimited supplies of labor”, The Manchester School, XXII, 139-91.

Murphy, K M, A Shleifer and R Vishny (1989), “Income distribution, market size, and industrialization”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(3), 537-564.

Stiglitz, J E (1996), “Some lessons from the East Asian miracle”, The World Bank Research Observer, 11(2), 151-177.

Endnotes

1 Banerjee and Duflo (2005) propose a similar model of development in which firms choose to upgrade to a new technology, but emphasise the role played by capital market imperfections in prohibiting the adoption of this technology.