When does distance learning work? Telesecundarias have operated in Mexico since 1968 and have succeeded in boosting student performance and closing urban-rural gaps. Mexico’s experience provides key lessons on designing effective remote education programmes.

The past decade has seen an increased interest in non-traditional schooling formats. Distance education, a broad category that includes any setting where the teacher and the student are not physically in the same room, has become both more popular and more controversial. On the one hand, there is clearly a demand for distance learning: By 2017-2018, 58.9% of U.S. public high schools offered an entirely online course. However, the Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the challenges of implementing distance education, with students in school districts that taught remotely for longer facing more severe learning losses. Whether distance education is likely to be effective depends on the quality of both the distance option and the local in-person alternative. In this article, we explore how Mexico’s experience can provide valuable insights for policymakers who aim to implement effective distance schooling options.

Mexico’s Telesecundarias – Education via television for students in rural areas

Throughout the twentieth century, Mexico struggled to attract qualified teachers to rural areas to instruct the millions of school-age children living there. Telesecundarias, which enroll students in grades seven through nine, were introduced in 1968 as a solution to this problem. The typical telesecundaria is a purpose-built structure with between three and nine classrooms, a library, restrooms, a science lab, and a playground. Telesecundaria students attend school for the same number of hours per week (30) and days per year (200) as students in traditional schools. What makes telesecundarias unique is that all lectures are delivered via television broadcast.

At telesecundarias, each subject begins with a fifteen-minute lecture that has been recorded in Mexico City by high-quality instructors. These so-called telemaestros are selected for their communication skills and undergo extensive training. The typical televised lecture requires twenty days of production time and costs $30,000-$50,000. The use of televised lectures eliminates a pressing labour shortage – the need to supply well-trained subject-specific teachers to sparsely populated areas of the country (Calderoni 1998). Rather than hiring separate teachers for math, history, Spanish and the like, telesecundarias have a single general teacher that supervises students during the televised lectures, leads them through a 35-minute lesson on the same subject following the lecture, and assigns and grades homework. These generalist teachers draw their lesson plans from teaching materials provided by the ministry of education that are designed to complement the televised lectures (Estrada 2003).

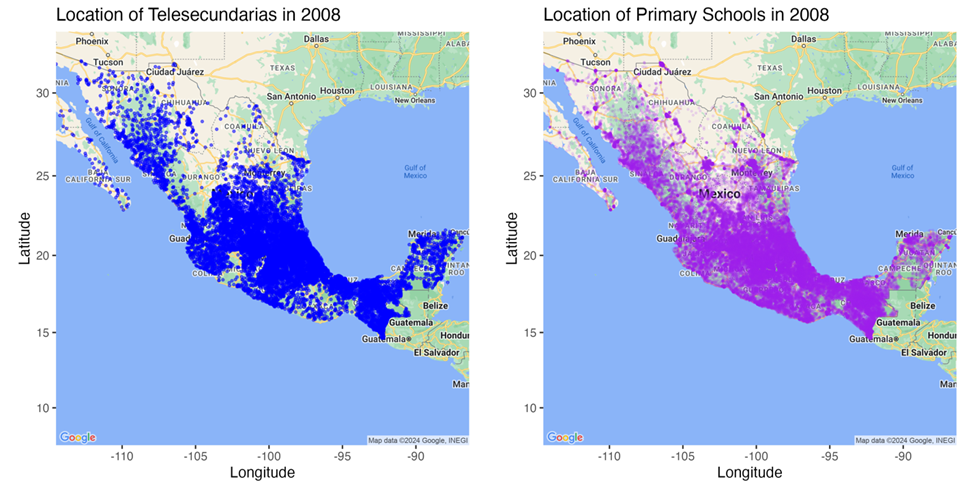

Telesecundarias were first introduced in rural areas predominantly in Mexico's poorer South, but they have since expanded throughout the country. By 2008, 17.7% of seventh grade students in Mexico attended a telesecundaria. Figure 1a depicts the location of all telescundarias that enrolled students in 2008 and complied with a national standardised exam. The figure shows that telescundarias are more prevalent in the center and south of the country, but a comparison with Figure 1b shows that they are typically located near primary schools.

Figure 1: Location of Telesecundarias vs primary schools

Telesecundarias and test scores

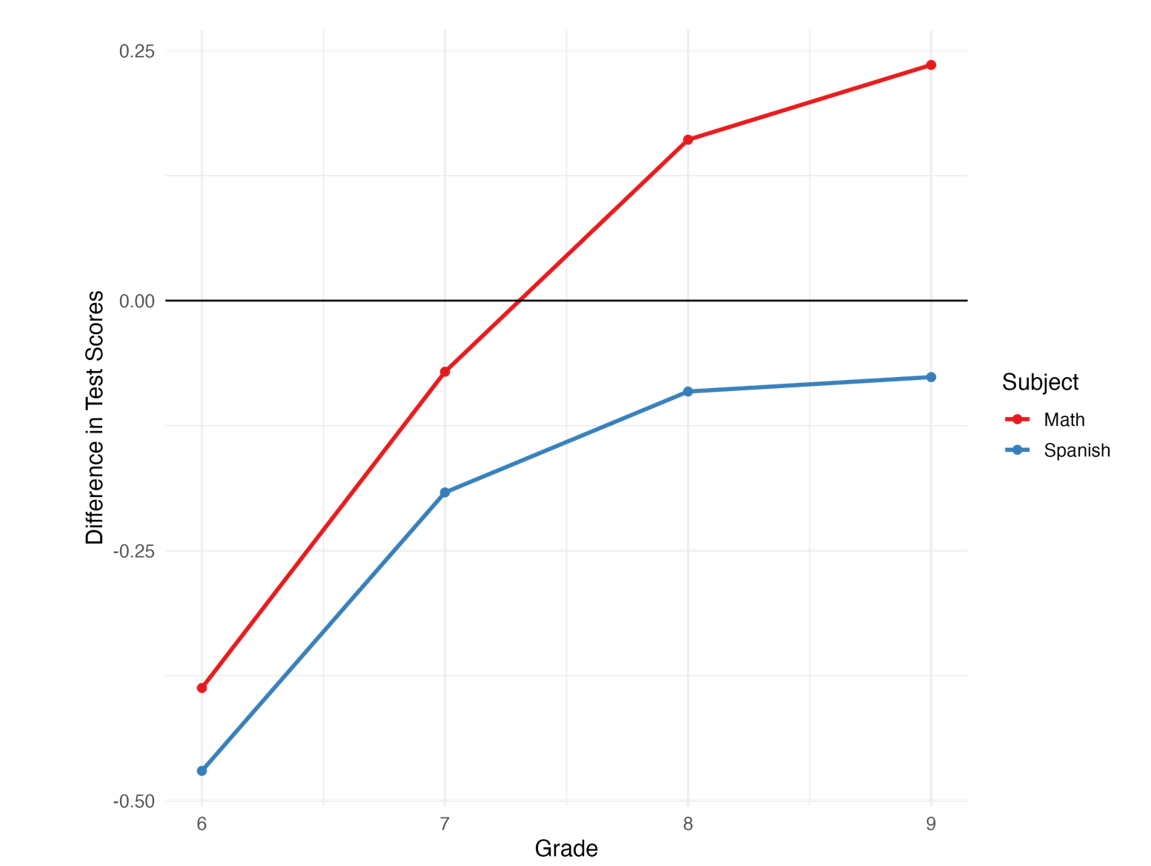

We analyse the effectiveness of telesecundarias relative to traditional public schools in Mexico using data on low-stakes end-of-year standardised tests in math and Spanish that have been shown to predict educational attainment and wages. We examine students who were in the sixth grade in 2007-2008 and who advanced to secondary school the following year. Figure 2 displays differences in mean scores on the exams between telesecundaria and traditional secondary school students. The figure shows that in grade six, the year prior to enrolling in secondary school, students who will attend telesecundarias the following year score 0.39 sd lower in math and 0.47 sd lower in Spanish, on average, than their peers who will attend traditional secondary schools. However, these gaps diminish considerably after students enroll in secondary school. By grade 9, telesecundaria students are performing 0.24 sd better in math and only 0.08 sd worse in Spanish.

Figure 2: Mean scores for telesecundaria and traditional secondary school students

The causal effect of Telesecundarias on student learning

The sustained improvement of telesecundaria students is striking, but a key challenge when analysing their effectiveness is that school attendance is not randomly assigned. We address this challenge by adopting a framework that jointly models the choice of school and test score outcomes for each student. This marginal treatment effects analysis sheds insight into the causal effect of telesecundaria attendance on test scores as well as what affects the decision to attend telesecundarias. (More details on methodology in our published paper.)

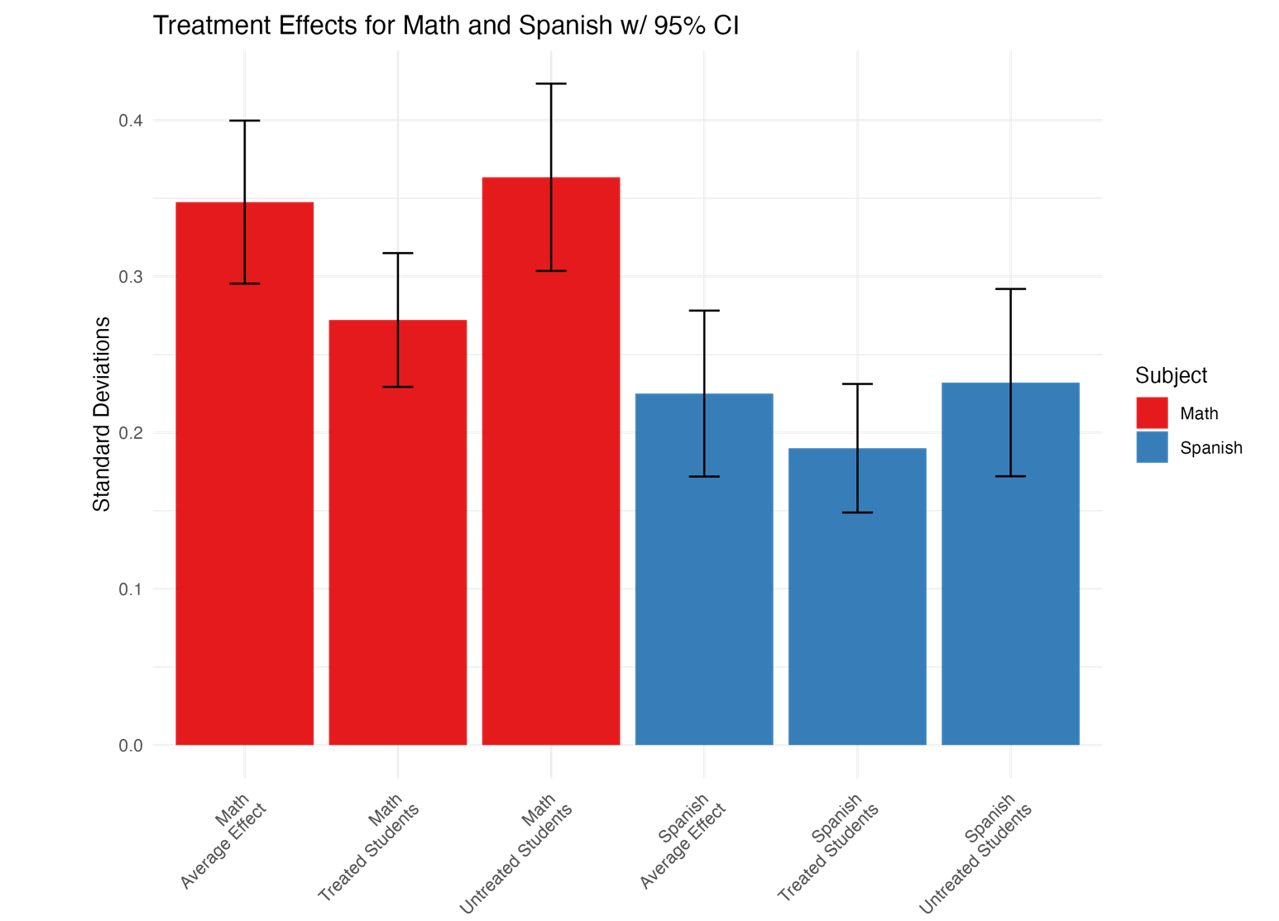

Figure 3 shows our main results. We find that telesecundarias cause average test score gains of 0.35 sd in math and 0.23 sd in Spanish after the first year of attendance. We additionally find that students who do not currently attend telescundarias would benefit more, on average, than students who currently attend them. This is shown in Figure 3 by estimates of the average effect for untreated students exceeding the average effect for treated students. This suggests that expansions of the telesecundaria programme will generate strong learning gains as they induce current traditional school students to switch to telesecundarias. Importantly, our analysis rules out the possibility that the marked improvement of telesecundaria students may be caused by differential rates of dropout, exam-sitting, or cheating between the two school types.

Figure 3: Treatment effects for Maths and Spanish

Consistent with contemporaneous work by Fabregas and Navarro-Sola (2024), we find that telesecundarias raise educational attainment. Attending a telesecundaria raises the probability that a student stays in school through the ninth grade by 2.8 percentage points. We also find that telesecundarias reduce the urban rural test-score gap, echoing findings from a distance learning initiative in China. This gap would be 128% larger in math and 43% larger in Spanish if telesecundarias did not exist. We additionally find that telesecundarias produce the greatest learning gains for students who enter secondary school with median test scores.

Policy implications: What can we learn from the effectiveness of telesecundarias?

The contrast between the effectiveness of telesecundarias and the experience of pandemic-era schooling can illuminate where distance education may be most effective. First, distance education will be more effective where in-person alternatives are poor. Scaling the lectures of one highly effective communicator likely outweighs mediocre in-person teaching. Second, it takes time and resources to develop an effective set of video lectures accompanied by supporting texts and assignments. The rapid ad hoc move to distance education during the pandemic contrasts greatly with the considerable attention and resources Mexico invests in each lecture. Lastly, distance education in Mexico is more beneficial for the median student. The weakest and strongest students may benefit more from the sort of impromptu assistance that teachers can provide in person but that is hard to automate. Policymakers who wish to develop effective distance education programmes would be wise to consult Mexico’s experience.

References

Borghesan, E and G Vasey (2024), “The Marginal Returns to Distance Education: Evidence from Mexico’s Telesecundarias,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 16(1): 253-85.

Calderoni, J (1998), “Telesecundaria: Using TV to Bring Education to Rural Mexico,” Education and Technology Team, Human Development Network, World Bank.

Estrada, R Q (2003), “Telesecundaria: Los Estudiantes y los Sentidos que Atribuyen a Algunos Elementos del Modelo Pedagogico,” Revista Mexicana de Investigacion Educativa, 8(17).

Fabregas, R and L Navarro-Sola (2024), “Broadcasting Education at Scale: Long-Term Labor Market Impacts of Television-Based Schools,” Working Paper.