Individuals put less effort into conserving water or energy at home when they share the resulting financial savings with other household members

Consumption of water and many energy sources can harm the environment and impose costs on others. The textbook solution is to raise the price such that people internalise the environmental externality. A puzzle in the literature is that residential customers’ water and energy use are quite price insensitive. A number of explanations have been suggested, including the complex pricing structures that utility companies use (Ito 2015), lack of awareness of one’s own use (Jessoe and Rapson 2014), and inattention to prices (Allcott 2011).

The theory

In recent work, we propose and investigate another explanation: free-riding within the household (Jack et al. 2018). Individuals enjoy private benefits from consumption but share the costs with other household members. This is because billing is at the household level, and the consumption of each household member is not easily observed. Thus, a free-riding problem ensues, wherein individuals consume more and are less price-sensitive than they would be if they bore the full cost of their actions. The problem is akin to the classic ‘moral hazard in teams’ problem in economics, in which workers put in less effort if they are rewarded for their team’s total output rather than their personal contribution.

Setting the context

To study this free-riding problem, we collaborated with the water utility in Livingstone, Zambia. We obtained water billing records for residential customers, a population that is middle class by Zambian standards, yet spends around 5% of monthly income on their water bill. For comparison, monthly piped water consumption is roughly half that of the average household in the US.

Predictions

We designed a field experiment to test two main predictions about how price responsiveness varies across individuals and households:

- Prediction 1: Existing incentives to conserve water will be especially weak for individuals who enjoy little of the benefit that results from the household’s water bill being lower. In our context, men are typically the ‘effective bill payers’, in the sense that when the bill is lower, men get to decide how the savings are spent. Women, therefore, have a lower stake in saving water, and we predict that their usage would be less responsive to household prices (and, conversely, more responsive to the introduction of person-specific prices, as explained below).

- Prediction 2: People who care more about how their decisions affect their family members will respond more to price changes. For instance, households in which spouses are more altruistic toward one another will be more responsive to changes in the household’s price of water.

Testing the predictions

Combining three ingredients to test the predictions

- We obtained monthly household water consumption data from our water utility partner’s billing records.

- We interviewed married couples, surveying each separately as well as simultaneously. This included playing a real-stakes modified ‘dictator game’, in which individuals are given choices over how much of their earnings to share with their spouse in a confidential decision. This decision captures the degree to which individuals maximise household rather than personal income. Sharing in the game provides a measure of how much each spouse internalises the other’s gains.

- We raised the price of water for a random subsample by offering a substantial cash prize if household water use fell to a specific target in subsequent months. The financial benefit of conservation was then the lower water bill plus the prize, so the prize effectively raised the price of water. Importantly, we varied whether the husband, the wife, or both spouses were informed about the prize (and later given the prize). Telling just one person is analogous to creating a person-specific price of water if individuals choose to keep the information private.

Results

On average, water use fell by 6.2% in response to the conservation prize, which implies a price elasticity of -0.27, similar to results on water demand in other contexts.

Prediction 1: Existing incentives around bill payment

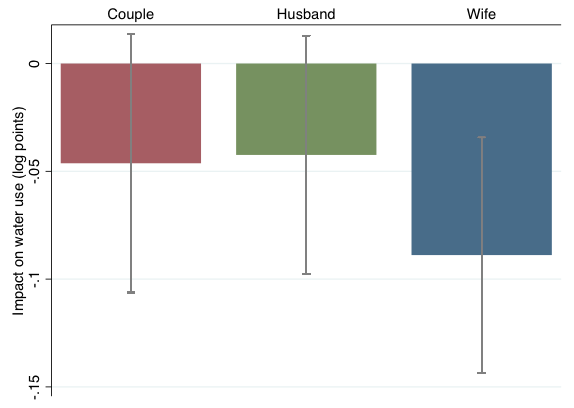

Women usually have the weaker status-quo incentive to conserve since men are the ‘effective bill payers’, and so an individual-specific price given to a woman generates an especially large change in her incentive to conserve. Consistent with this, we found that offering the conservation prize to the wife led to a roughly 9% reduction in water use, versus a 4-5% reduction if given to the husband or to both spouses (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Estimated impacts on water use in response to the conservation prize offered to the couple, husband, or wife

Women are not always the ones with weak incentives to conserve; sometimes the man is the likely free-rider because the woman is the effective bill payer. We tested whether what really matters is the recipient’s gender or his or her existing incentives and found that the answer is incentives. Water use declined most when the prize was given to whoever was not the effective bill payer, controlling for that person’s gender. Thus, how savings from water conservation are divided up within the home is a key determinant of household water use.

Prediction 2: Income-sharing among spouses

We also found that couples who were more altruistic toward each other were more responsive to the conservation prize. Households with above-median sharing in the dictator game were four times as price responsive as those with below-median sharing, implying that altruism among family members affects how households respond to prices. Spouses might also share more with each other in the game if they can recoup what they share. The ability to enforce informal contracts in the home also helps households overcome free-riding in water consumption.

Policy implications

Environmental externalities from water use (for example, harm to the critical ecosystem of the Zambezi River, which is Livingstone’s water source) suggest that a tax is needed to achieve the socially efficient consumption level. The extra inefficiency that our work highlights, in that households consume too much even from their own perspective, implies that the tax needs to be higher. However, a recent insight from behavioural economics is that if households vary in the degree of their internal inefficiency, i.e. if some are better and some are worse at overcoming free-riding, then the optimal tax should be set to only partially solve the inefficiency (Taubinsky and Rees-Jones 2016). Our calculations suggest that the optimal price in our setting is 17% higher because of household free-riding, which leaves water consumption still higher than it would be absent intrahousehold free-riding.

Caveats and directions for future research

Our study focused on the dynamics between husbands and wives, although households include children and other members too. The incentive problems that we have described likely extend to these other relationships, and more work is needed to understand, for example, how parents and children negotiate around water and energy use.

Our study was also not designed to test scalable policy solutions. Person-specific prizes for conservation allowed us to test for the importance of intra-household free-riding, but are not a feasible long-term policy, since water is billed at a household and not individual level.

As discussed above, taxes may be unable to fully address both the environmental externality and the intra-household problem. Addressing intra-household free-riding directly may therefore be valuable. One idea is to provide richer information to households about their usage through smartphone apps or smart meters; real-time data on household-level usage would help in estimating and monitoring each individual’s usage. In addition, technologies that make conservation easier (e.g. water-saving appliances) might be especially valuable when it is difficult to align incentives within the home.

References

Allcott, H (2011), “Consumers’ perceptions and misperceptions of energy costs”, American Economic Review 101(3), 98–104.

Ito, K (2014), “Do consumers respond to marginal or average price? Evidence from nonlinear electricity pricing”, American Economic Review 104(2), 537–563.

Jack, K, S Jayachandran and S Rao (2018), “Environmental externalities and free-riding in the household”, NBER Working Paper no. 24192.

Jessoe, K and D Rapson (2014), “Knowledge is (less) power: Experimental evidence from residential energy use”, American Economic Review 104(4), 1417–1438.

Taubinsky, D and A Rees-Jones (2016), “Attention variation and welfare: theory and evidence from a tax salience experiment”, NBER Working Paper no. 22545.