Psychosocial factors matter for financial behaviour. A financial literacy and parenting programme substantially improves families’ financial lives.

A life in poverty is characterised by a day-to-day struggle for securing food and basic needs. The poor are forced to carefully juggle their expenses, decide between difficult trade-offs, and cope with irregular incomes and a high frequency of emergencies and income shocks (Collins et al. 2009). While financial management for those living in high-income countries is usually eased by several default arrangements (i.e. our salary is paid into bank accounts, our insurance contributions are automatically deducted), the poor are lacking such supportive financial infrastructure. Considerable decision-making burden canput a ‘tax’ on their mental bandwidth, deplete cognitive resources, and potentially result in suboptimal financial decisions and behaviours (Schilbach et al. 2016, Lichand and Mani 2016). Consequently, poverty perpetuates itself.

In response, many development programmes haveput focus on facilitating financial planning and decision making among the poor. Most prominently, financial literacy programmes have been used to promote financial knowledge and to teach financial management skills. However, they have had a rather poor track record to date, with several meta-analyses documenting null effects, particularly in low-income populations (Steinert et al. 2018a, Kaiser and Menkhoff 2017, Fernandes et al. 2014). Building on this, recent research has started to explore innovations in intervention designs that could increase effectiveness and relevance of financial literacy programmes.

New (holistic) programme designs

In this respect, scholars have argued that financial behaviour is not only a function of economic scarcity and financial knowledge but is also shaped by a range of psychological and social factors. Put differently, our capacity to save money or to resist to temptation spending is likely also defined by our willpower, self-efficacy, self-worth, and our perceptions about the future, as well as by the behaviour of the peers around us (Blattman et al. 2017, Heller et al. 2017, Mani et al. 2013). Some previous interventions have sought to capitalise on exactly these skills while trying to promote economically relevant outcomes. For instance, the Sustainable Transformation of Youth in Liberia (STYL) programme coupled distribution of unconditional cash transfers with cognitive behavioural therapy (Blattman et al. 2017). A programme for female sex workers in India delivered a ‘dream-building intervention’ to promote hope, agency, and self-worth in addition to offering saving accounts (Ghosal et al. 2015), and interventions in Uganda (Riley 2018) and Ethiopia (Bernard et al. 2014) presented inspirational stories and positive role models to foster entrepreneurial and educational aspirations, hope, and forward-looking financial behaviour.

Our study

Building on this emerging body of literature, we collaborated with the World Health Organisation and UNICEF to develop a multi-faceted intervention thatcombined brief financial literacy training with a family-based parenting programme. Our programme curriculum is thus based on two key pillars:

- a psychosocial pillar, geared towards forming supportive and nurturing relationships within families and communities, promoting optimism, confidence, and self-efficacy; and

- a financial literacy pillar, featuring budgeting training and saving motivation for precautionary purposes.

The curriculum covers 14 weekly sessions at three hours and was delivered by lay social workers and trained community members to groups of parents and their 10 to 18 year-old teenagers.

We conducted a cluster randomised control trial to determine the impact of this intervention on participants’ financial behaviour and financial welfare (Steinert et al. 2018b). We enrolled 552 families from the Eastern Cape province of South Africa, selecting one adult (the primary caregiver) and one teenager1 per participating household. Families in our sample were quite poor –a third lived in informal housing (‘shacks’). They reported an average of almost three week-days without sufficient food in their homes, and their main income source was monthly governmental welfare grants. Twenty villages and peri-urban townships were randomly assigned to receive the combined parenting and financial literacy intervention (the treatment group). The remaining 20 villages and townships received an unrelated one-day hygiene intervention (the control group). We collected data at baseline (i.e. before the interventions) and five to nine months post-intervention, using self-administered interviewing techniques that were programmed on mobile tablets.

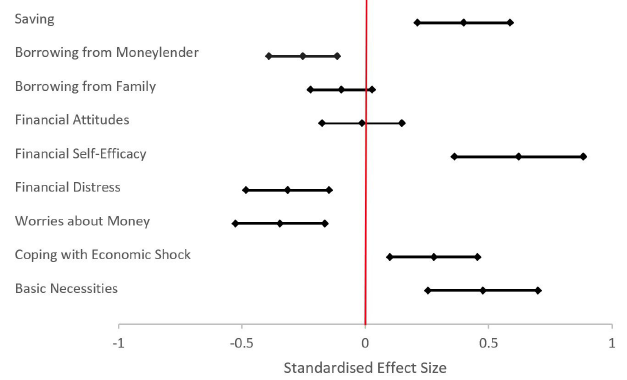

Our findings reveal that the intervention had substantial impacts on participants’ financial behaviour and even on their wider economic wellbeing. Specifically, we documented significantly higher past-month saving rates among treatment group participants. Participants also borrowed less from moneylenders, known in the Eastern Cape for taking extremely high interest rates. In addition, participants reported substantially higher levels of financial self-efficacy, while financials attitudes remained unchanged. More importantly, we found some substantial effects on household economic welfare. This was expressed in significantly reduced past-month financial distress, better resilience to income shocks, and a greater capacity among treatment group families to secure a range of basic needs, including sending their children to school and to the doctor when needed. Figure1 presents our main results graphically in standardised effect sizes.

Figure 1 Intent-to-treat programme effects for adult participants

Unpacking mechanisms of change

Positive changes in financial behaviour were associated with significant improvements in optimism, self-efficacy, positive family relationships, and community social support. Drawing on qualitative data from focus group discussions and in-depth interviews, we gathered further support for the central role of psychological and social factors. Here, programme participants noted that they felt more confident and empowered to save and budget their money.Participants also indicated higher levels of hope and optimism – which seemed to have helped them shift their time preferences more towards the future and towards building future savings.Lastly, saving and budgeting norms were reinforced through positive interactions with peers and family members. For instance, participants described how monthly budgeting became a shared and collaborative activity in their families.

Implications

Our findings have important implications for policy and practice. They suggest thatpsychological and social factors are not static and ‘given’ but are malleable and can thus be turned into important target points for development interventions (Campos et al. 2017). Hence, future poverty alleviation programmes could bolster their effectiveness by integrating psychosocial elements into their curricula. In addition, our findings may contribute to the improved functioning of South Africa’s cash transfer system for poor families by empowering and enabling recipients to make the most effective and informed use of their monthly grant money.

References

Bernard, T, S Dercon, K Orkin and A Taffesse (2014), “The future in mind: Aspirations and forward-looking behaviour in rural Ethiopia”, Working Paper No. 429, BREAD.

Blattman, C, JC Jamison and M Sheridan (2017), “Reducing crime and violence: Experimental evidence from cognitive behavioural therapy in Liberia”, American Economic Review 107(4): 1165–1206.

Campos, F, M Frese, M Goldstein, L Iacovone, H Johnson, D McKenzie, D and M Mensmann (2017), “Teaching personal initiative beats traditional training in boosting small business in West Africa”, Science 357(6357), 1287–1290.

Collins, D, J Morduch, S Rutherford and O Ruthven (2009), Portfolios of the poor: How the world’s poor live on $2 a day, Princeton University Press.

Fernandes, D, J Lynch and R Netemeyer (2014), “Financial literacy, financial education, and downstream financial behaviours”, Management Science 60(8): 1861–1883.

Ghosal, S, A Mani, S Jana, S Mitra and S Roy (2015), “Sex workers, self-image and stigma: Evidence from Kolkata brothels”, Working Paper, University of Warwick.

Heller, S, A Shah, J Guryan, J Ludwig, S Mullainathan and H Pollack (2017), “Thinking, fast and slow? Some field experiments to reduce crime and dropout in Chicago”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 132(1): 1–54.

Kaiser, T and L Menkhoff (2017), “Does financial education impact financial literacy and financial behaviour, and if so, when?”, The World Bank Economic Review 31(3): 611–630.

Lichand, G and A Mani (2016), “Cognitive droughts”, Working Paper, Harvard University.

Mani, A, S Mullainathan, E Shafir and J Zhao (2013), “Poverty impedes cognitive function”, Science 341(6149): 976–980.

Riley, E (2018), “Role models in movies: The impact of Queen of Katwe on students’ educational attainment”, Working Paper, University of Oxford.

Schilbach, F, H Schofield and S Mullainathan (2016), “The psychological lives of the poor”, American Economic Review 106(5): 435–440.

Steinert, J, J Zenker, U Filipiak, A Movsisyan, LD Cluver and Y Shenderovich (2018a), “Do saving promotion interventions increase household savings, consumption, and investments in sub-Saharan Africa? A systematic review and meta-analysis”, World Development 104(C): 238–256.

Steinert, J I, L D Cluver, F Meinck, J Doubt and S Vollmer (2018b), “Household economic strengthening through financial and psychosocial programming: Evidence from a field experiment in South Africa”, Journal of Development Economics 134: 443-466.

Endnotes

[1] Here, we focus on adult family members, assuming that they are mainly responsible for the financial management in the household.