Subsidising entrepreneurs to hire a marketing or accounting specialist can be more effective than trying to train the entrepreneur in these skills

Editors’ note: To learn more about improving businesses practices, read our revised VoxDevLit on Training Entrepreneurs.

Across a range of countries, firms with better management and business practices, like financial record-keeping and marketing activities, are more profitable, more likely to survive, and grow faster (Bloom and Van Reenen 2007, McKenzie and Woodruff 2017). Since many small firms do not use a lot of these practices, the typical policy response has used business training programmes to attempt to teach entrepreneurs these skills – with more than US$1 billion spent on entrepreneurship training annually (McKenzie et al. 2020).

However, it is difficult to get firm owners to take time away from their businesses. Thus, most training courses tend to be short in length and have limited impact on firms’ adoption of new practices. On average, the typical training programme improves business practices by five percentage points. If a course tries to teach firm owners 20 new practices, they adopt one of them on average (McKenzie and Woodruff 2014).

During its initial years, the entrepreneur is often synonymous with the firm. However, as the firm grows, the boundary between the entrepreneur and the firm widens, and the entrepreneur must make decisions about which business activities to carry out herself and what to hire others to do. That is, there is a boundary within the firm (which we refer to as the ‘boundary of the entrepreneur’) as well as at the firm’s edge – i.e. the traditional ‘boundary of the firm’.

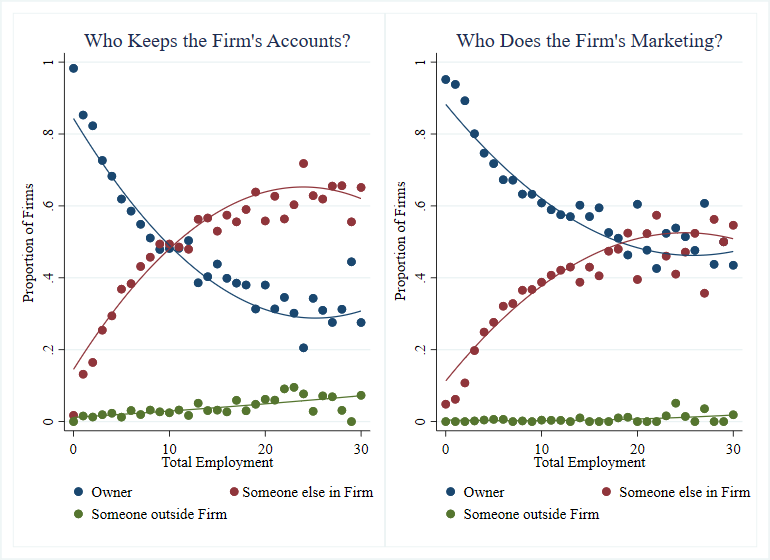

Figure 1 shows that by the time firms reach 10 to 20 workers, the boundary of the entrepreneur has started to shift. Half of all firms have someone other than the entrepreneur in charge of the finance and/or marketing functions. Thus, if the goal is to help small firms grow, rather than training the owner it may be more effective to help entrepreneurs access a marketplace for business services where they can hire skilled specialists.

Figure 1 Entrepreneurs are less likely to do the finance and marketing tasks in larger firms

Source: Baseline data on 8,071 Nigerian firms who applied for different forms of support under the Nigerian Growth and Employment (GEM) project. See Anderson and McKenzie (forthcoming) for more details.

In a new paper (Anderson and McKenzie, forthcoming), we test this idea through a pilot embedded in the Growth and Employment (GEM) project in Nigeria. This project initially planned two approaches to helping firms gain business skills:

- Business training, where firms receive 25 hours of online training followed by 12 days of in-person training (based on the Business Edge curriculum) and at a cost of approximately US$ 2,000 per firm.

- Matching firms with consulting service providers, who receive 88 hours of personalised consulting spaced over six to nine months at a cost of US$ 4,000 per firm.

Testing insourcing and outsourcing as alternatives to business training

We worked with the GEM project to pilot two alternative approaches requiring the same amount of funding as the training. However, funds were instead used to help firms access a marketplace where they could hire for these skills. With insourcing, firms could contract a human resources provider to help them find and hire a marketing or finance specialist to work full-time in their business. They received a subsidy that would first cover the full cost of this worker, before declining over time so that the firm was covering most of the cost after eight months. With outsourcing, firms could contract an accounting or marketing service provider, whose specialist would typically work one day per week with the firm, with a declining subsidy spread over nine months.

In contrast to training and consulting, which largely tell an entrepreneur how to do things themselves the functional specialist directly implements tasks and carries them out on an ongoing basis.

We tested the relative effectiveness of these different approaches through a randomised experiment in Lagos and Abuja. A sample of 753 firms with two to 15 workers who had applied for the GEM programme were randomly assigned into five groups of approximately 150 firms each: A control group, business training, consulting, insourcing, and outsourcing.

The firms were looking to grow, were run by owners who almost all had some tertiary education, and were earning approximately US$ 1,000 per month in profits at baseline. Half were in light manufacturing, and the remainder in ICT, hospitality, entertainment, or construction. We then measured impacts over two years with programme administrative data and two follow-up surveys with 89% and 86% response rates.

Market-based insourcing and outsourcing approaches were more effective at improving business practices than business training

We carefully measured 41 different business practices, including many that could be objectively verified. Business training had a small and not statistically significant impact on these practices (Figure 2). In contrast, both insourcing and outsourcing resulted in statistically significant improvements in a range of business practices. Most firms given the insourcing or outsourcing treatments chose to hire marketing specialists and, in line with this business support, we find eight to 10 percentage point improvements in marketing and digital marketing practices.

Figure 2 Two-year impacts on business practices

Note: Figure shows treatment impacts on the proportion of business practices implemented, along with 95% confidence intervals. Impacts were similar in the first year as the second.

These improvements in business practices lead to higher sales, profits, and employment over the next two years.

Sourcing strategies were at least as effective as consulting, at half the cost

Our sample size was smaller than planned, reducing statistical power to detect these impacts, but we find statistically significant improvements in these outcomes for both outsourcing and consulting. We cannot reject that the insourcing intervention had the same effect as these other two approaches, but also cannot reject that it had no effect.

The magnitude of the increase in profits for outsourcing is approximately US$ 100 per month, which is enough to recoup the cost of the subsidies in just over one year, and full cost of the programme for this group in under two years. The main mechanisms for this firm growth are through product innovation and improved social media technologies. The marketing specialists helped firms identify products to introduce that customers wanted. Firms also improved both the quantity and quality of their digital marketing, helping them reach more customers. Revealed preference also shows that many firms found this beneficial, with firms keeping at least one-third of their specialists after the subsidy period ended and being more likely to go back to the market to buy more services.

Policy implications

Insourcing and outsourcing appear to be a promising way to help firms improve their business practices, and may be a useful alternative to the standard business training programmes. A natural question then is why do firms not just buy these services on their own. That is, what is the role for government policy?

A first reason firms may not use these services is due to information frictions in the market for these business services. Our project helped screen business service providers for quality, and provided firms with a list of service providers they could choose from. In a follow-up experiment (Anderson and McKenzie 2021), we find that firms lack information about these providers and that their preferences for providers respond to quality ratings. However, this information alone is not enough to get firms to start using insourcing or outsourcing services. Hence, while governments may play a role in reducing information frictions, direct subsidies may be needed to help firms see the value of these services through demonstration. This is not just the case for developing countries, where government support to improve management practices is an important part of the historical and present development of many advanced economies (Giorcelli 2021). Atherton et al. (2002) and Ezell and Atkinson (2011) argue that public support for these services can then in fact be ‘market-making,’” by helping SMEs understand the value of these services and building future demand.

References

Anderson S and D McKenzie (forthcoming) “Improving Business Practices and the Boundary of the Entrepreneur: A Randomized Experiment Comparing Training, Consulting, Insourcing and Outsourcing”, Journal of Political Economy, forthcoming.

Anderson S and D McKenzie (2021) “What prevents more small firms from using professional business services? An information and quality-rating experiment in Nigeria”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 9614.

Atherton A, T Philpott and L Sear (2002) “A Study of Business Support Services and Market Failure”, European Commission. .

Bloom, N and J Van Reenen (2007) “Measuring and Explaining Management Practices Across Firms and Countries”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(4): 1351-1408.

Ezell, S and R Atkinson (2011) “International Benchmarking of Countries’ Policies and Programs Supporting SME Manufacturers”, The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, September.

McKenzie D and C Woodruff (2014) “What are we learning from business training evaluations around the developing world?”, World Bank Research Observer 29(1): 48-82.

McKenzie D and C Woodruff (2017) “Business Practices in Small Firms in Developing Countries”, Management Science 63(9): 2967-81.

McKenzie D, C Woodruff, K Bjorvatn, M Bruhn, J Cai, J Gonzalez Uribe, S Quinn, T Sonobe, and M Valdivia (2020), “Training Entrepreneurs”, VoxDevLit 1(1)