Engaging in open conversations about stigmatised topics like menstruation reduces the social barriers to health technology adoption, which increases access to welfare-improving menstrual products

A powerful global movement has taken on the stigma surrounding menstruation. From sports leaders to government officials, people are getting behind the hashtag #LetsTalkPERIOD(s) to normalise menstruation and advance menstrual health.

Globally, there have been huge advances in the willingness to tackle the impact stigma and taboos have on menstruation. Public and private institutions have embraced inventive approaches to dismantle the silence surrounding menstruation, with initiatives spanning collaborations with sports teams to partnerships with influencers. For example, the German Women’s World Cup football team teamed up with o.b. tampons (sparking conversations even at matches), and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) leveraged social media and local influencers, to reshape discussions across Nepal, Albania, and the Philippines.

Menstrual health and hygiene in low and middle-income countries

The adoption of menstruation-specific products remains limited in many low and middle-income countries. Despite the numerous initiatives aimed at enhancing menstrual health, such as local production of sanitary pads and menstrual health education in schools, the results have shown only partial success. For example, in Bangladesh, where there have been substantial efforts to improve the accessibility and affordability of sanitary pads, uptake is persistently low. Even where products are accessible and affordable, adoption remains low, with over half of the menstruating population continuing to rely on old cloth and rags for menstrual management (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics 2020). Cleaning and drying these materials is challenging, and infection risk is high (Torondel 2018). Menstruation continues to be shrouded in shame and stigma in Bangladesh (Castro & Czura 2021) and many other countries, resulting in poor management of menstrual health and hygiene.

Existing studies aimed at mitigating the adverse health effects of inadequate menstrual hygiene have primarily concentrated on providing information and removing financial obstacles to accessing menstruation-specific products like sanitary pads. Research by Czura et al. (2023) shows that providing information and distributing sanitary pads for free enhances the uptake of these products. Comparable studies in the realm of preventive healthcare have revealed that disseminating information and offering complimentary supplies can positively influence behavior, yet the challenge lies in fostering actual adoption. This pattern is observable across various domains, where individuals tend to neglect investments in preventive healthcare, even if the costs are minimal and they acknowledge the associated benefits (Luoto et al. 2014, Dupas et al. 2016, Null et al. 2018, Dupas et al. 2020, John and Orkin 2022).

Social barriers to menstrual health and hygiene in Bangladesh

The recent work of Castro and Mang (2022), examines social and psychological barriers to the adoption of both established and novel menstrual products in Bangladesh. The study addresses two pivotal questions: does stigma affect women’s access to menstrual products? and what happens when we start talking openly about a stigmatised topic?

The research addresses a possible explanation for the limited increase in pad usage and the persistence of unhygienic menstrual management (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics 2020), and argues that perceived social constraints are stopping the widespread adoption of modern products and practices. These constraints take various forms. Menstrual taboos exacerbate misinformation and prejudices because they prevent open, informed, and public discussion at home and in the classroom. In Bangladesh only 30% of women hear about menstruation before reaching menarche (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics 2020). In the sample of Castro & Mang (2022) 2.3% of the women learned about menstruation at school, less than half learned about it from their mother and 19.6% did not know about menstruation at all before they experienced their first period.

Also, the stigma can extend to discomfort about being seen purchasing pads in a convenience store or pharmacy. In Bangladesh, outlets that sell pads are operated almost exclusively by men, and talking with someone of a different gender about menstrual products might conflict with social norms. Women experience a trade-off between accessing menstrual-specific products and the fear of stigmatisation, social discomfort about mentioning a taboo topic, or concern about contravening social norms.

Figure 1: Woman purchasing at a pharmacy in Dhaka (Bangladesh) in November 2021 (By Romana Hasan)

Castro and Mang (2022) document that women report at baseline that they are affected by social concerns when contemplating the purchase of sanitary pads. A survey asked the participants who use menstrual cloth as their only absorbent to report the main reason for not switching to pads. The vast majority (85%) report the presence of men in the store as the main reason. When measuring the current social norms related to the purchase of the product, the majority of women believe that it is perceived by their peer group as socially inappropriate to purchase pads from a male shop clerk (60%).

Breaking the silence through group discussions at the workplace

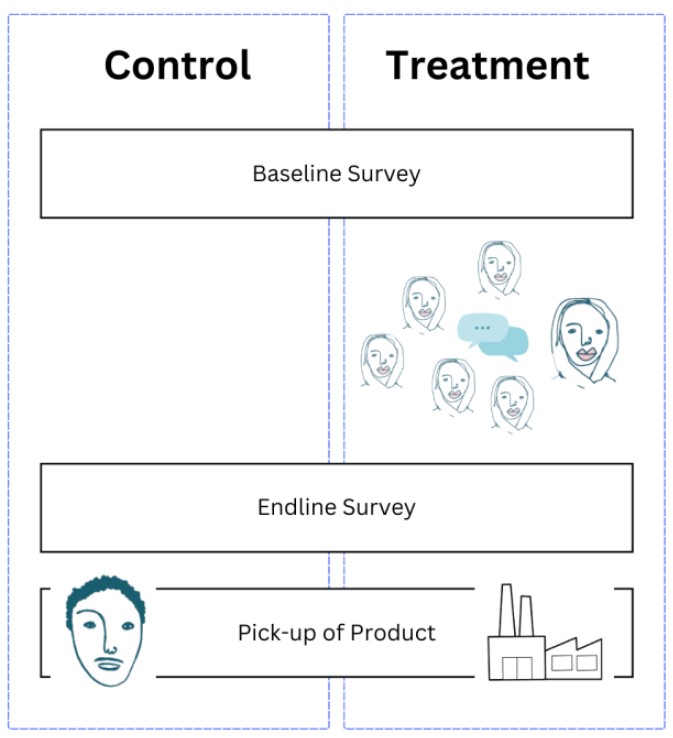

To test for stigma as a constraint, Castro and Mang (2022), in collaboration with the social enterprise Reemi, use a randomised control trial with female participants in a garment factory near Dhaka. The garment factory employs more than 5,000 workers out of which, 450 workers were chosen randomly to take part in the study. Half of the participants were further randomly allocated into group discussions about periods.

During these discussions, between 15 and 20 women gathered during work hours for a one-hour guided conversation. The facilitator initiated the discussion and encouraged participants to share their thoughts about the topic. No extra information was introduced from outside, and the person leading the talk made sure that the women felt confident to talk and share - their goal wasn't to correct or change anyone's beliefs, but simply to let the topic be heard and make it normal to discuss.

Figure 2: Intervention design

The intervention increases take-up and valuation of menstrual products

Two metrics were used as primary outcomes. First, we measured the participants’ valuation of sanitary pads (using an incentivised willingness to pay exercise). Second, an innovative antibacterial reusable menstrual underwear that is not yet available in Bangladesh was offered to them for pick up at the factory’s convenience store - the collection rates of this product formed the second metric. The outcomes of women who participated in the discussion were compared to the control group, which did not participate in any discussion sessions. To mimic market conditions, the products had to be picked up from a male shopkeeper at the convenience store of the factory, where other customers could be present.

Castro and Mang (2022) document an increase in the valuation of sanitary pads and in the take-up rates of the new menstrual underwear. The treatment significantly increases the women’s willingness to pay for sanitary pads by more than 25% compared to the control group’s average valuation of 90 BDT (∼ 1 USD). Second, it increases the adoption of anti-bacterial menstrual underwear. The take-up rates increase by 14% for the treatment group when compared to a 71% adoption rate among the control group.

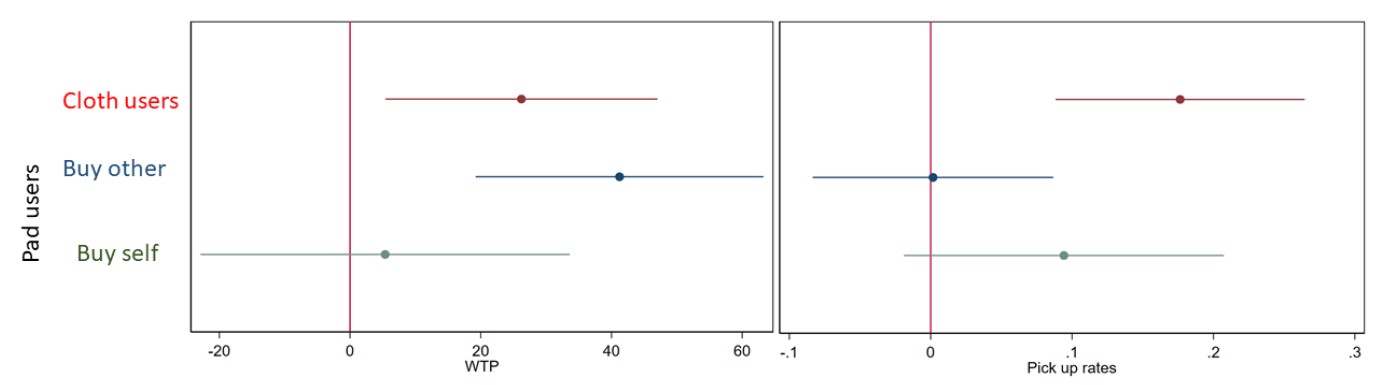

Also, an intriguing insight from the study is how individuals are influenced based on their starting behaviors. Initially, 40% of participants relied solely on cloth, while 60% used pads, with half of these not personally procuring the pads themselves from the market and relying on their husband or a friend for the purchase. Across these three participant groups, the changes in collection rates are predominantly driven by those who used only cloth initially (the collection rate for this group is 26% higher than in the control group). Strikingly, women who had never used any menstruation-specific products before are now embracing the new menstrual underwear at a higher rate than others.

Figure 3: Changes in valuation of sanitary pads and take-up rates of the new menstrual underwear

On the other hand, the willingness to pay increase is most significant among women who were already using pads but did not buy them themselves. The increase in valuation is 45% for this group, compared to the control (they value pads at 132 BDT compared to the 90.8 BDT valuation for the control group); the increase is 31% for the cloth users, whereas there is no change for the women who were already using, and self-purchasing, pads. This suggests that these women, who already understood the benefits and preferred sanitary pads, but who were not buying the pads themselves, experienced a shift in perception during the group discussions. They realised that other women were accessing and independently purchasing their own pads

Channels of change: Less importance is given to the gender of the shopkeeper and the visibility of the purchase

The important question that remains is what are the factors driving the increase in take-up rates and valuation. Castro and Mang (2022) disentangle three channels:

- Information dissemination: The discussion could raise awareness among women about menstrual products they were previously unfamiliar with, potentially altering their perception of these products solely through the transmission of information.

- Women's attitudes towards acquiring menstrual products from a male shopkeeper: Open discussions have the potential to provide updates on current social norms. Women might mistakenly believe that their peers consider it socially inappropriate to purchase pads from a male shop clerk. After participating in the discussion, women may realise that some of their peers do buy pads themselves and that the social norms are not as strict as initially thought due to the taboo on the topic.

- Anonymity and privacy when purchasing menstrual products: In the presence of stigma, individuals attempt to distance themselves as much as possible from the stigmatised condition. Consequently, they would strive to buy pads in private settings, which can often be challenging. The study documents 50% of the participants report covering their face with a burka when buying pads. One potential outcome of the discussion could be the reduction of stigma, thereby empowering women to publicly purchase the product when needed.

We employ a discrete choice experiment to disentangle the impact of these three channels. Importantly, while the information channel cannot explain the difference in take-up rates, as the menstrual underwear was unknown to them until well after the discussions had concluded, it could explain differences in valuation.

This exercise shows that two of these factors influence women’s decisions and rules out the information channel. Overall, a higher price, purchasing from a male instead of a female shopkeeper, and collecting the product at a location inside the factory (where there is less anonymity) produce disutility, with shopkeeper gender having the largest impact. Importantly, picking up the underwear from a man, or in a less anonymous location, creates less disutility for the women who participated in the group discussions. Lastly, we observe that the intervention has no effect on the price that the participants associated with the product, as there is no difference in the valuation of this attribute between the control and treatment groups. Therefore, at the endline, the treatment and control groups differ in their concerns about picking up the product at a public location, and from a male shopkeeper, but they do not differ in how they perceive the value of the product. This clearly points to a social image channel: the discussion helps to normalise the topic and reduce concerns about gender and publicity of the purchase, and is not acting through information provision.

Policy implications

Turning menstruation into a topic that can be openly discussed, and disseminating health and hygiene information, has clear and tangible effects on the adoption of innovative new health products. Additionally, it triggers significant changes in people's perspectives toward products that are already available. Open discussions can successfully lessen the societal stigma attached to menstruation, and empower women and people that menstruate in all parts of society. This normalisation makes it acceptable for users to access these welfare improving products.

References

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (2020), “National Hygiene Survey,” 122.

Castro, S and K Czura (2021), "Social Norms and Misinformation: Experimental Evidence on Learning About Menstrual Health Management in Rural Bangladesh" CESifo Working Paper No. 9081, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3848343 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3848343

Castro, S and C Mang (2022), "Breaking the Silence - Group Discussions, Social Pressure, and the Adoption of Health Technologies", Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4081416 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4081416

Czura, K, A Menzel and M Miotto (2023), "Improved Menstrual Health and the Workplace: An RCT with Female Bangladeshi Garment Workers." CESifo Working Paper No. 10289

Dupas, P, V Hoffmann, M Kremer, and A Peterson Zwane (2016), “Targeting Health Subsidies through a Nonprice Mechanism: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Kenya.” Science 353(6302): 889–895.

Dupas, P, B Nhlema, Z Wagner, A Wolf, and E Wroe (2020), “Expanding Access to Clean Water for the Rural Poor: Experimental Evidence from Malawi.” NBER Working Paper No. 27570.

Luoto, J, D Levine, J Albert, and S Luby (2014), “Nudging to Use: Achieving Safe Water Behaviors in Kenya and Bangladesh.” Journal of Development Economics 110:13–21.

Torondel, B, S Sinha, J R Mohanty et al. (2018), "Association between unhygienic menstrual management practices and prevalence of lower reproductive tract infections: a hospital-based cross-sectional study in Odisha, India." BMC Infect Dis 18:473. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3384-2

John, A, and K Orkin (2022), "Can Simple Psychological Interventions Increase Preventive Health Investment?", Journal of the European Economic Association 20(3): 1001-1047.

Null, C, C Stewart, A Pickering, H Dentz, N Arnold, C Arnold, J Benjamin-Chung, T Clasen, K Dewey, L Fernald, et al. (2018), “Effects of Water Quality, Sanitation, Handwashing, and Nutritional Interventions on Diarrhoea and Child Growth in Rural Kenya: A Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial.” The Lancet Global Health 6(3): e316–e329.