Female inheritance might create unintended consequences for young women’s freedoms due to patriarchal practices designed to retain property within families

Development economists show that supporting women’s inheritance rights is an effective policy to empower women in developing countries (Deininger et al. 2013, Heath and Tan 2019). However, social scientists such as Goody (1976) have long noticed that female inheritance might also result in constrained marriage and gender norms for women if it is not accompanied by actual property ownership.

In male-dominated societies, female inheritance often means that women function mainly as carriers of property from father to husband, rather than as active managers of their property. Therefore, a woman’s marriage determines whom her family will have to share their land with. This creates incentives for her male relatives to control her marriage decision and premarital relations. In my paper (Bahrami-Rad 2019), I provide evidence of this phenomenon.

Constraints of inheritance on young women

As the literature suggests, when a woman inherits or is due to inherit land, her extended family attempts to arrange her marriage to a cousin because such marriage arrangements allow the bride and groom to pool land parcels and capital goods. This decreases land and capital fragmentation and helps to preserve viable land holdings for farming. This is more feasible than pooling resources with outsiders, which is usually costly due to imperfect capital markets in developing countries.

Arranging a woman’s marriage with a cousin also requires restricting her premarital love and sexual relationships. If a love relationship is not prevented, it might lead to marriage with an outsider, because family ties are not central in love relationships. Further, because of restrictions on their premarital relations, young women are more likely to meet and fall in love with their cousins, who are among the few people of the opposite sex they are allowed to socialise with.

But why are restrictions imposed mostly on women, not men? By creating stigma around unwanted pregnancy and loss of virginity, patriarchal societies find it easier to control women’s premarital relations, and therefore, their incumbent property entitlements.

Evidence from India: Cousin marriage and premarital relations

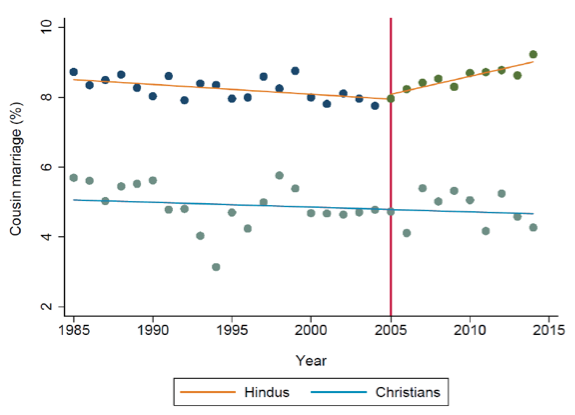

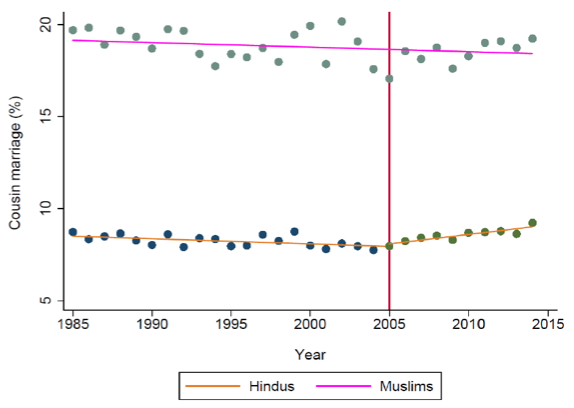

The 2005 amendment of the Hindu Succession Act of India introduced female inheritance to Hindu families in many regions of India. The Act applies only to Hindus and explicitly exempts Muslims and Christians. In a difference-in-differences analysis, I use Hindu women married in or after 2005 as the treated group, since their marriage choices are exposed to the amendment. As the comparison group, I use Hindu women married before 2005 and all Muslim and Christian women in the sample.

My analysis shows that exposure to the amendment has significantly increased cousin marriage and decreased premarital sex among Hindu women by 1% (the means of both cousin marriage and premarital sex rates among Hindu women are below 10%). Robustness and placebo tests do not reject the parallel trends assumption.

Figure 1

Note: Compared with the five-year period (2000–2004) before the amendment of the Hindu Succession Act in 2005, the average cousin marriage rate of women married after the amendment increased significantly among Hindu women (Wald test p-value<0.001), while it did not change significantly among Muslims and Christians (Wald test p-value=0.417 and 0.371 respectively).

Evidence from Indonesia: Arranged versus love marriage

Further, running a regression analysis on survey data from Indonesia, I find that among Indonesian women, inheriting property from parents is positively associated with being engaged in an arranged marriage where the parents of a bride chose her husband (versus love marriage where the bride chooses her husband by herself).

In an additional analysis, and to rule out the possibility of reverse causality, I define separate variables for inheriting property before and after marriage. The coefficients of the two variables are not significantly different – that is, even if a woman inherits property after her marriage, she is still more likely to be engaged in an arranged marriage. This tells us that future inheritance expectations might influence women’s marriage decisions just as much as the actual inheritance itself.

These arrangements and controls may negatively impact women’s participation in society. Using Indonesian data, I show that inheriting property from parents is positively associated with self-employment among men. However, this positive association is missing for women.

Historical evidence: A pattern of constraints

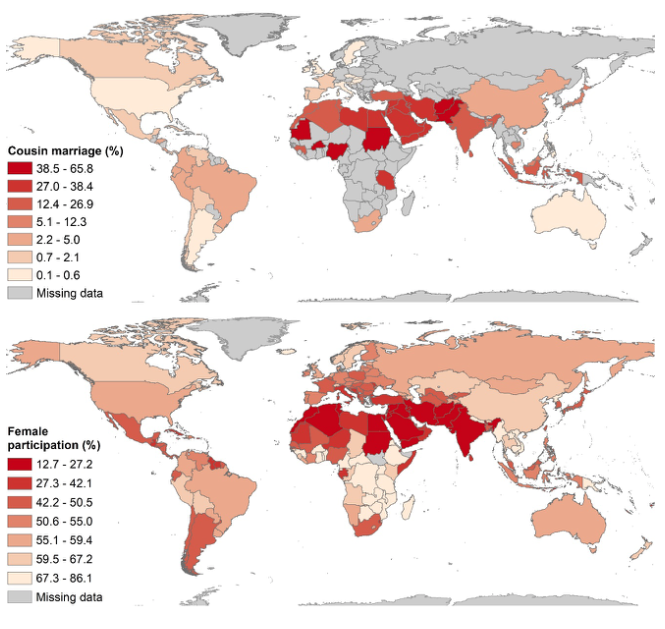

Using data on 1,291 globally distributed pre-industrial societies, I also show that the patterns I have described hold historically. Societies that traditionally practiced female inheritance were also more likely to allow cousin marriage, and less likely to allow female economic participation and premarital sex. This could have important implications for understanding marriage and gender norms in Islamic countries.

Today, cousin marriage rates are highest (32%) and female participation rates are lowest (27%) in the Middle East and North Africa. The cousin marriage culture and unequal gender norms in this region might be partly explained by the fact that Islam is the only religion that formally specifies women’s inheritance rights.

Figure 2

Note: Cousin marriage rates (up to and including second cousins) around the world (Bittles and Black, 2015). Labour force participation rate of women above 15 years old, 2010–2016 estimates by the International Labour Organization, with darker colors indicating lower percentages.

Policy implications: Ownership enjoyment is key

Under patrilineal restrictions on women’s empowerment in developing countries, the mere enacting of female inheritance laws does not ensure women’s property ownership (Roy 2015) and equality for them in all aspects of life. It might even create some unintended consequences for young women’s sexual lives and marital choices (see also Anderson and Genicot, 2015). Therefore, to promote women’s empowerment through female inheritance laws, policymakers should also devise complementary policies to guarantee that women actually own and are able to exploit their property.

References

Anderson, S and G Genicot (2015), “Suicide and property rights in India”, Journal of Development Economics 114: 64–78.

Bittles, A and M H Black (2015), “Global patterns and tables of consanguinity”, www.consang.net.

Deininger, K, A Goyal, and H Nagarajan (2013), “Women’s inheritance rights and intergenerational transmission of resources in India”, Journal of Human Resources 48: 114–141.

Bahrami-Rad, D (2019), “Keeping It in the Family: Female Inheritance, Inmarriage, and the Status of Women”.

Goody, J (1976), “Production and reproduction: A comparative study of the domestic domain”, Cambridge Studies in Social Anthropology 17.

Heath, R and X Tan (2019), “Intrahousehold bargaining, female autonomy, and labor supply: Theory and evidence from India”, forthcoming in Journal of the European Economic Association.

Roy, S (2015), “Empowering women? Inheritance rights, female education and dowry payments in India”, Journal of Development Economics 114: 233–251.