Prior engagement with NGOs boosts intervention effectiveness, which should be accounted for when evaluating research conducted with local implementation partners

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) play increasingly important roles as implementers of development interventions. Over 80% of currently financed World Bank projects, for example, involve the participation of an NGO or a civil society organisation, compared to just 21% in 1990 (World Bank 2013). In recent years, NGOs have also emerged as vital partners for conducting applied development research. NGOs implemented almost 40% - the single largest share - of all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published in top economics journals between 2009 and 2014 (Peters et al. 2018). Despite this growing influence, rigorous analyses of the effects that NGOs have on outcomes are rare (Brass et al. 2018), and little is known about what it is about NGOs - what they do, where they work, or a bit of both? - that drives the success of the interventions they implement.

We show that the effectiveness of an intervention designed to promote cleaner energy technologies in a rural setting was at least 30% higher in communities with prior exposure to a development NGO (Usmani, Jeuland and Pattanayak forthcoming), suggesting that the trust and social capital NGOs foster among beneficiaries over time is a key driver of implementation efficacy. This ‘NGO reputation effect’ has implications for the generalisability and scalability of evidence from experimental research conducted with local implementation partners.

Design: How should we account for non-random NGO location

NGOs are highly selective about where they operate (Fruttero and Gauri 2005), which implies that communities with active NGOs differ significantly from those without. Comparing the effectiveness of interventions in these two groups of communities cannot provide a clear understanding of the extent to which NGOs drive observed differences in outcomes.

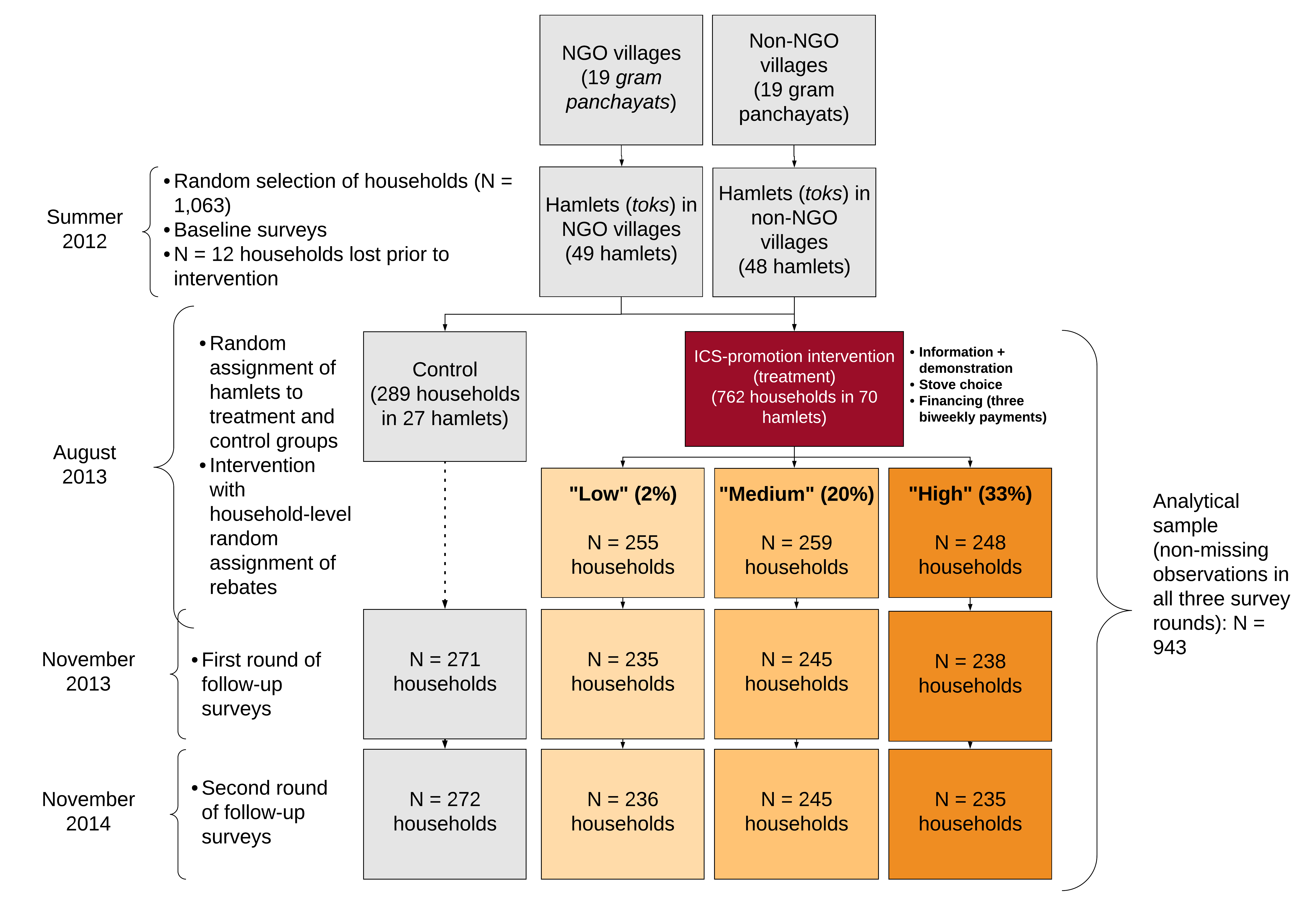

Figure 1: Study design and timeline

Note: “Low,” “medium,” and “high” refer to rebates randomised at the household level (rebate amount in parentheses).

To address this concern, we designed a matched-experimental study in the Indian state of Uttarakhand, where a reputed development NGO is active (Figure 1). First, we identified all 148 ‘NGO villages’ in which this NGO had previously worked. Then, using matching techniques applied to census data on village-level characteristics, we identified a sample of ‘non-NGO villages’ that were observationally similar across many dimensions, but had not previously had any such contact or prior working relationship with this NGO. During the matching process, we paid particular attention to contextual factors that are commonly associated with the presence of NGOs, such as population, distance from nearby towns, and the quality of village-level infrastructure (Brass 2012). After eliminating poorly matched villages, our sample consisted of 38 villages (19 matched pairs of NGO and non-NGO villages). Within each matched village, we randomly selected two to four geographically distinct hamlets, ending up with a total of 97 hamlets. We then randomly selected a total of about 1,000 households from these hamlets for baseline surveys.

Following baseline data collection, we randomly assigned approximately 70% of hamlets to receive an intervention aimed at increasing demand for improved cookstoves (ICS). We thus had treatment and control hamlets in both NGO and non-NGO villages. Importantly, the intervention - consisting of information provision, ICS demonstrations, a rebate randomised at the household level, and an offer to purchase up to two types of devices - was implemented by independent, newly hired, and trained sales staff who identified themselves as affiliated with the NGO.

NGO boosts intervention effectiveness by over 30%

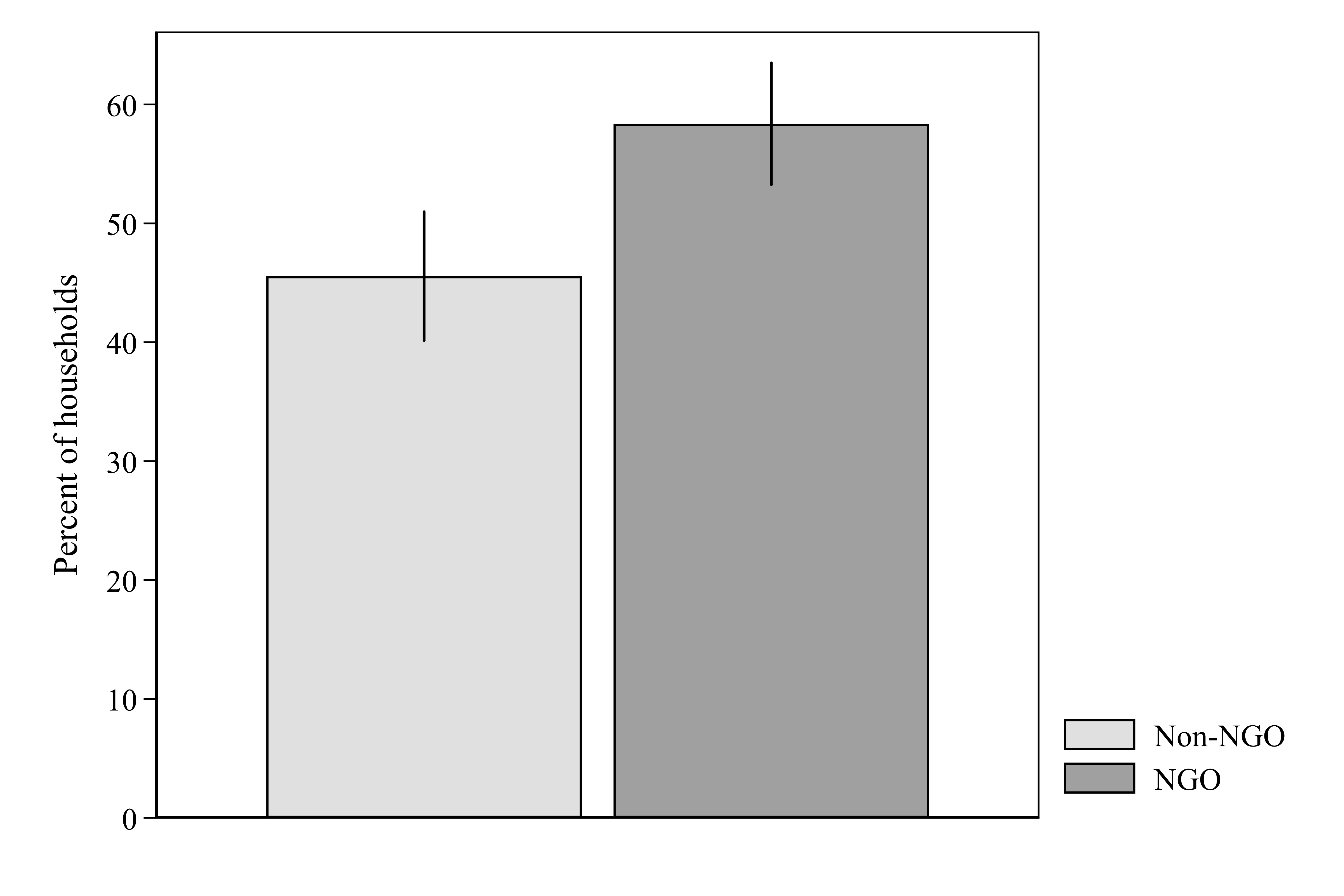

We found that over 50% of households targeted by the intervention purchased at least one promoted device, indicating high demand for ICS in the sample communities (Pattanayak et al. 2019). Differences between NGO and non-NGO communities, however, were large: nearly 60% of targeted households in NGO villages purchased an ICS, compared to only 45% in non-NGO villages (Figure 2). This positive NGO reputation effect corresponds to a 31% increase in the intervention’s effectiveness.

Figure 2: ICS purchase rates in treated hamlets in NGO and non-NGO villages

Note: Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals for the means.

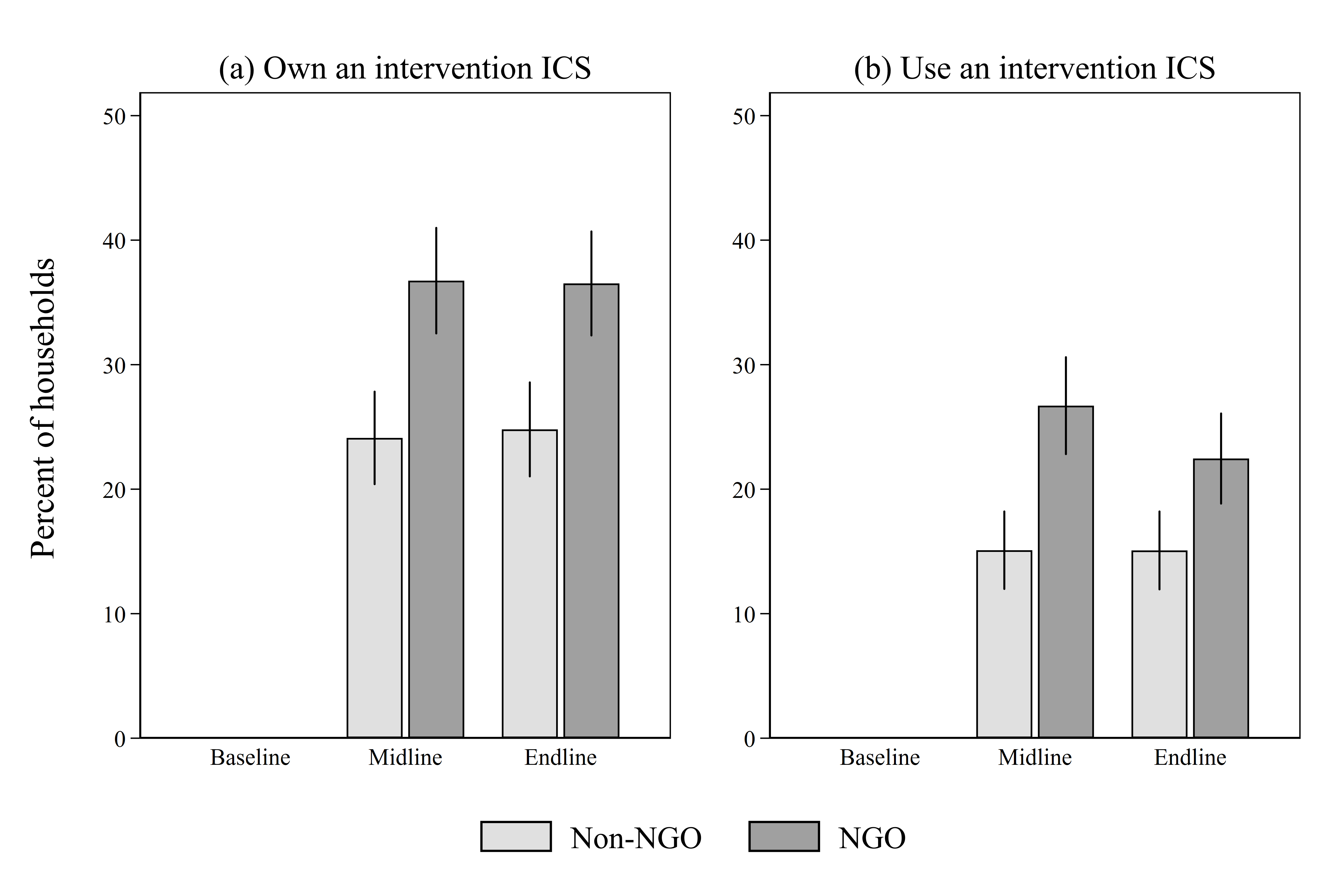

The positive impact of the NGO’s prior relationships was not limited to initial purchases. Using data from two follow-up survey rounds and controlling for unobserved time-invariant household-level characteristics, we found that households in treated-NGO hamlets were up to 16 percentage points more likely to continue to own and use the ICS devices over time than those in non-NGO hamlets, representing a 50 - 80% increase in the size of the treatment effect (Figure 3).

Figure 3: ICS ownership and use in NGO and non-NGO villages

Note: The midline and endline survey rounds correspond, respectively, to three and fifteen months following the intervention. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals for the means.

Finally, this divergence in ICS adoption rates also translated into differential welfare gains. ICS use can deliver environmental, health, and development benefits by reducing households’ reliance on polluting fuelwood (Jeuland et al. 2020). Consistent with this, we found that households in treated-NGO hamlets used less fuelwood over time and reported spending less time collecting fuel per day. In contrast, the energy-use patterns of households in treated hamlets in non-NGO villages were indistinguishable from those of control households not exposed to the intervention.

Synthesis: Learning from the evidence

To better understand how our findings contribute to the limited evidence on how NGOs shape outcomes, we used a simple Bayesian regression framework to combine our data with insights from a nascent literature on the importance of implementer identity, which finds that NGO-led interventions are often more effective than those implemented by other actors (e.g. Cameron et al. 2019, Fischer et al. 2019, Fitch-Fleischmann and Kresch 2021). First, through a review of this literature, we identified three main insights:

Studies that compare NGOs side-by-side with other types of implementers (e.g. Bold et al. 2018) find that NGOs are 10 - 60% more effective.

A meta-analysis finds that effect sizes of NGO-implemented programs are 113% higher than those of government-implemented ones (Vivalt 2020).

- No study reports that NGOs perform worse than other types of implementers. In fact, some studies (e.g. Grossman et al. 2020) report extremely large, positive differences in effect sizes between NGO- and non-NGO-led intervention, depending on contextual factors.

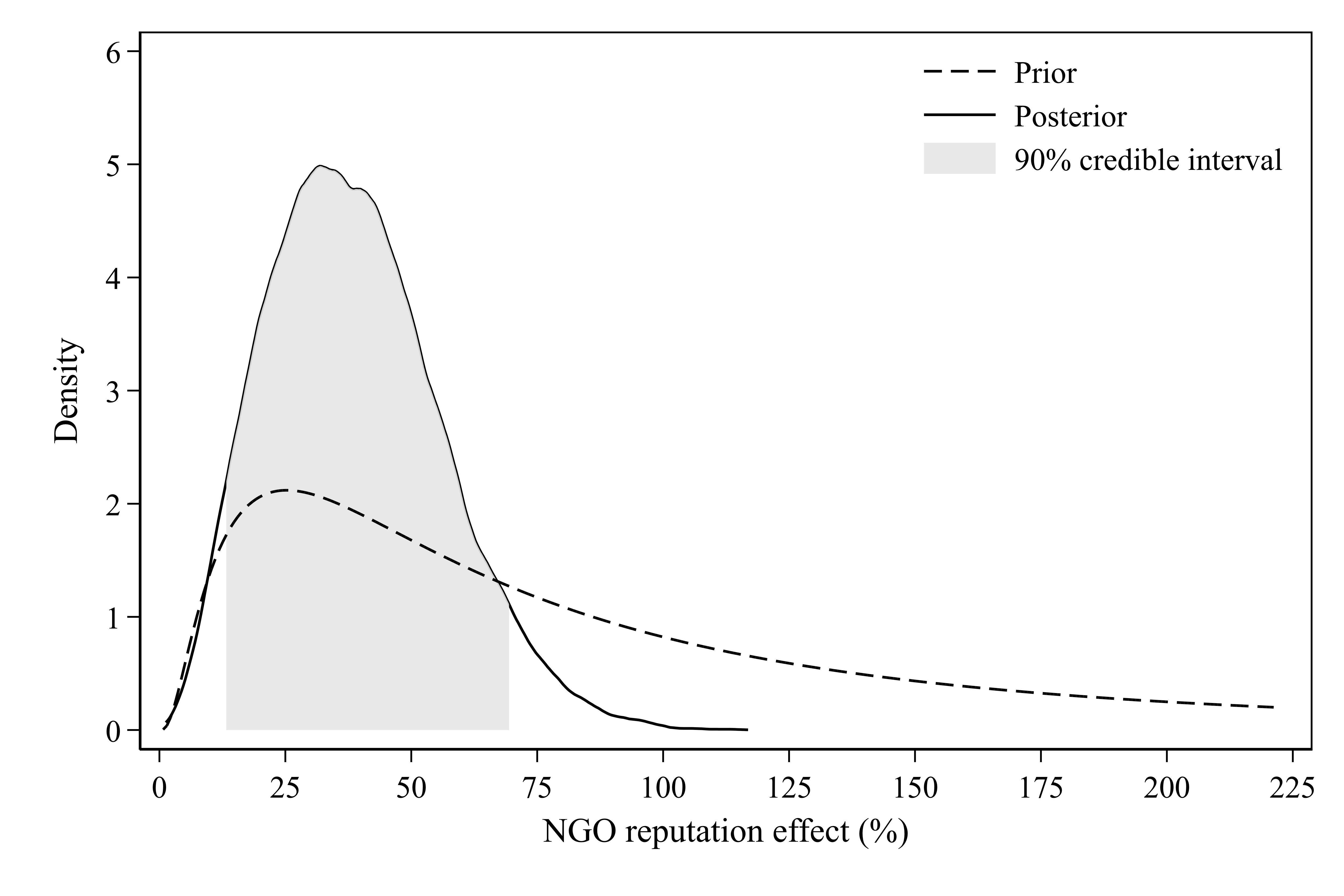

Based on these insights, we then specified a prior distribution for the NGO reputation effect (dashed line in Figure 4) to characterise the existing evidence, and used it to inform a Bayesian regression model. In doing so, we learned two things.

First, the resulting posterior distribution (solid line in Figure 4) has considerably less density in its right tail, reflecting our updated beliefs given this specified prior and our data. In particular, the 90% credible interval (the range that contains the true effect with a posterior probability of 0.9) suggests that an implementing NGO’s prior relationships with beneficiaries can increase intervention effectiveness by 13 - 70%. Second, the estimated posterior mean is 39%. Given that our study focused on an implementing NGO’s prior relationships with beneficiaries whereas most of the existing literature compares NGOs with other types of implementers suggests that, taken together, the NGO reputation effect explains about a third of the overall difference between NGO and non-NGO implementers estimated by Vivalt (2020).

Figure 4: Bayesian analysis of heterogeneity in ICS purchase across NGO and non-NGO hamlets

Note: This figure plots prior and posterior distributions of the regression parameter that represents the additional effect of the ICS promotion intervention on purchase rates in treated NGO hamlets relative to treated non-NGO hamlets. The x-axis is relabelled to highlight relative percentage changes. The prior is a Lognormal (−1.17, 1) distribution. The posterior distribution is estimated via Markov chain Monte Carlo simulation. See Usmani et al. (forthcoming) for additional details.

Conclusion

Clearly there is something about NGOs that drives their success, as previous research has shown. However, we build on this work to show how sustained engagement with a trusted local NGO - and the resulting reputation effect that entails - directly influences household decision-making and ultimately determines intervention effectiveness.

As such, we offer two main insights. First, from a scientific perspective, we must be careful in interpreting results from experimental research conducted in partnership with NGOs and other civil society organisations. Any claim that such findings will generalise is unwarranted if the role of those partner institutions is not adequately accounted for. Second, from a policy perspective, effective NGOs are critical for implementing environmental, health, and development interventions, especially in remote, rural settings. Policymakers looking to scale up successful interventions may do better by building in the time and resources needed for enlisting and engaging well-regarded partners with meaningful local reputational capital.

References

Bold, T, M Kimenyi, G Mwabu, A Ng’ang’a, and J Sandefur (2018), “Experimental evidence on scaling up education reforms in Kenya”, Journal of Public Economics 168: 1–20.

Brass, J N (2012), “Why Do NGOs Go Where They Go? Evidence from Kenya”, World Development 40(2): 387–401.

Brass, J N, W Longhofer, R S Robinson, and A Schnable (2018), “NGOs and international development: A review of thirty-five years of scholarship”, World Development 112: 136–149.

Cameron, L, S Olivia, and M Shah (2019), “Scaling up sanitation: Evidence from an RCT in Indonesia”, Journal of Development Economics 138: 1–16.

Fischer, G, D Karlan, M McConnell, and P Raffler (2019), “Short-term subsidies and seller type: A health products experiment in Uganda”, Journal of Development Economics 137: 110–124.

Fitch-Fleischmann, B and E P Kresch (2021), “Story of the hurricane: Government, NGOs, and the difference in disaster relief targeting”, Journal of Development Economics 152: 102702.

Fruttero, A, and V Gauri (2005), “The Strategic Choices of NGOs: Location Decisions in Rural Bangladesh”, The Journal of Development Studies 41(5): 759–787.

Grossman, G, M Humphreys, and G Sacramone-Lutz (2020), “Information Technology and Political Engagement: Mixed Evidence from Uganda”, The Journal of Politics 82(4): 1321–1336.

Jeuland, M, J Peters, and S K Pattanayak (2020), “Do improved cooking stoves inevitably go up in smoke? Evidence from India and Senegal”, VoxDev.org, April 6.

Pattanayak, S K, M Jeuland, J J Lewis, F Usmani, N Brooks, V Bhojvaid, A Kar, L Lipinski, L Morrison, O Patange, N Ramanathan, I H Rehman, R Thadani, M Vora, and V Ramanathan (2019), “Experimental evidence on promotion of electric and improved biomass cookstoves”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 7: 201808827.

Peters, J, J Langbein, and G Roberts (2018), “Generalization in the Tropics – Development Policy, Randomized Controlled Trials, and External Validity”, The World Bank Research Observer 33(1): 34–64.

Usmani, F, M Jeuland, and S K Pattanayak (forthcoming), “NGOs and the effectiveness of interventions”, The Review of Economics and Statistics.

Vivalt, E (2020), “How Much Can We Generalize From Impact Evaluations?”, Journal of the European Economic Association 18(6): 3045–3089.

World Bank (2013), World Bank–Civil Society Engagement: Review of Fiscal Years 2010–12, Washington, DC: World Bank.