Employment is more likely to be reduced when the minimum wage is binding, in the formal sector, when enforcement is strong, and for vulnerable workers

Evidence from studies of the employment effects of minimum wages in developing countries is mixed. Does this mean there is simply no clear evidence of disemployment effects in developing countries? Or do theory and institutional factors that vary across countries and studies explain the variation in the evidence, with estimated effects more consistently negative in studies with relatively more features for which institutional factors and the competitive model more strongly predict negative effects?

To study this question, we reviewed 61 papers on the employment effects of minimum wages in developing countries (Neumark and Munguía Corella, forthcoming). We selected these papers by searching on Google Scholar for published and unpublished papers, for all the regions in the developing world, and also consulted recent surveys (Belman and Wolfson 2016, Broecke et al. 2017). We restricted the analysis to papers that report employment elasticities with respect to the minimum wage, or that provided enough information to compute these elasticities.

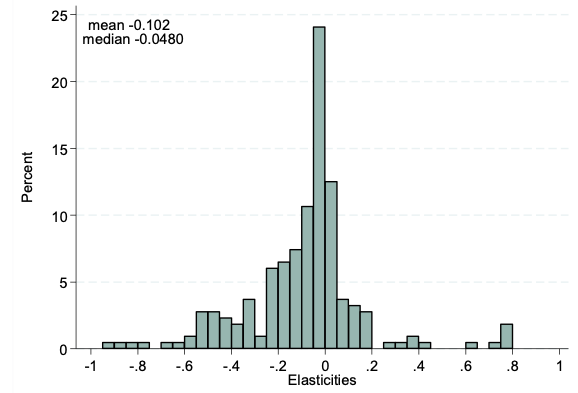

Simple averaging of the authors’ preferred estimates from each study yields an elasticity of −0.102. However, looking across all the studies reveals considerable heterogeneity, with many negative estimates (some substantially larger in absolute value than these averages) but also many (although fewer) positive estimates (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Histogram of authors’ preferred elasticities in surveyed studies

Note: We drop from the histograms (but include in the means and medians) the observations that are larger than 1 in absolute value to eliminate outliers and because most of the observations are between −1 and 1.

The competitive model and institutional factors predict that adverse employment effects are more likely under some conditions than others – such as a strongly enforced minimum wage for lower-skilled workers

Our goal was to try and understand this heterogeneous evidence and what we can learn from it. Is there simply no consistent evidence of negative employment effects of minimum wages in developing countries? Or is there more evidence of negative effects where we would expect them – for example, vulnerable low-skill workers where minimum wage laws are strong and binding – but not for higher-skill workers or where minimum wages laws are weaker and/or less binding?

To answer these questions, we classify the estimates in the studies in our survey by specific features of the estimates. We then ask whether features of estimates that are more likely to predict negative effects either based on economic theory – specifically, the competitive model of the labour market – or because of institutional factors, do in fact do so. We classify estimates based on four features:

- Whether minimum wages are binding, based on evidence of a positive effect of the minimum wage on average wages

- Whether they pertain to the formal sector, informal sector, or both (total employment); in the formal (or ‘covered’) sector, minimum wage laws apply in principle; in the informal sector, minimum wages could increase employment (Harris and Todaro 1970)

- The degree of enforcement of minimum wage laws: no enforcement (countries whose laws do not penalise violations of the minimum wage law); weak enforcement (countries that have low-cost fees for a violation); and strong enforcement (countries whose laws specify severe penalties for not abiding by the law, like time in prison or shutdown of the company) (Munguía Corella 2019)

- Whether they are for low-skilled or ‘vulnerable’ workers (young adults, for women, or unskilled workers), or instead, for all workers

Under the competitive model, at least, it is more likely that minimum wages reduce employment when the minimum wage is binding, in the formal sector, when enforcement is strong, and for vulnerable workers.

Minimum wages are more likely to reduce employment for a binding minimum wage, with stronger enforcement, in the formal sector, and for vulnerable workers

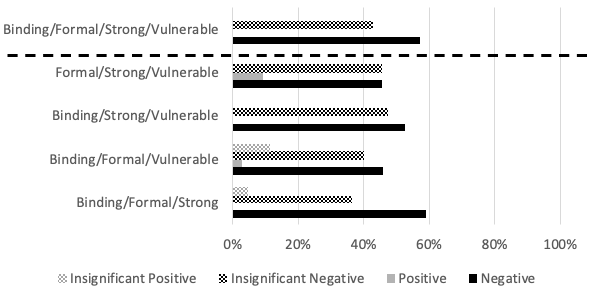

One way to display the evidence from estimates with more or fewer features predicting adverse employment effects is depicted in Figure 2, which presents evidence on the sign and significance of the estimates for estimates for which three or more features more strongly predict negative employment effects. In Panel A, the first set of bars (above the horizontal dashed line) are for all four features. All of these estimates are negative, with 57.1% significant and 36.7% insignificant. The remaining sets of bars are for estimates for each set of three features that more strongly predict negative employment effects. Nearly all of the estimates are negative, and more are statistically significant than not.

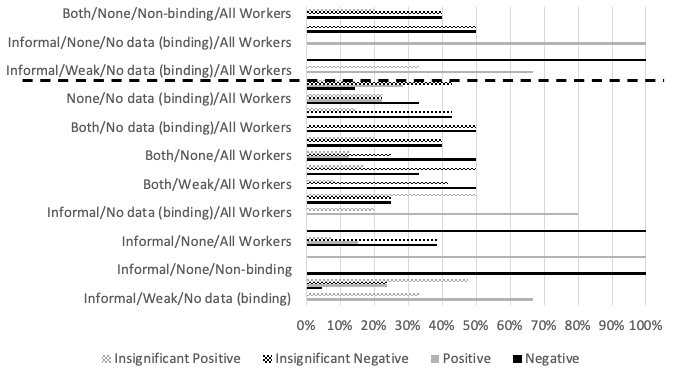

Panel B, in contrast, summarises results for estimates for which three or (all) four features do not more strongly predict negative employment effects. There is no clear pattern of more negative than positive elasticities, and there are many sets of features for which there are more positive than negative effects – for example, informal/weak/all workers and informal/weak/no data (binding).

Our paper presents different kinds of evidence assessing how features of estimates impact their sign and significance. The different analyses deliver quite a clear message: when studies of the employment effects of minimum wages in developing countries have many (or most) features that more strongly predict negative employment effects, based on the competitive model and institutional factors (such as stronger enforcement), the evidence is a good deal more likely to point to negative employment effects.

Figure 2 Results by features of estimates, authors’ preferred estimates, sign and significance

A) Three or four features more strongly predict negative effects

B) Three or four features do not more strongly predict negative effects

Note: Entries with no estimates are not shown. Entries above the dashed line are for four-way classifications of features of estimates. Results labelled “Positive” or “Negative” have p-values ≤ 0.05. See notes to Figure 2A. “None” refers to no enforcement, and “Weak” to weak enforcement. “Both” refers to covering the formal and informal sectors combined.

Minimum wages are likely to reduce employment the most where the potential to help low-wage workers may appear to be the greatest

We conclude that one can draw firmer conclusions about the employment effects of minimum wages in developing countries than first meets the eye when simply looking at all the estimates. We find that the estimated employment effects of minimum wages in developing countries are more likely to be negative, and larger negative, when estimates focus on data and sectors for which the competitive model predicts disemployment effects, and in institutional settings in which we would expect the minimum wage to have more adverse impacts. Specifically, there is more consistent evidence of negative employment effects when the minimum wage is binding, where minimum wage enforcement is stronger, for estimates of effects in the formal sector, and when the data focus on more vulnerable (lower-wage) workers.

Our evidence leads to a few key conclusions:

- Stronger and more consistent evidence of adverse employment effects under conditions where we would expect adverse effects – for less-skilled workers, when minimum wages are binding or strongly enforced, or in the formal sector – does not negate the fact that estimated employment effects in developing countries vary. Rather, the evidence informs us regarding the institutional settings and contexts in which minimum wages reduce employment.

- Our evidence suggests that minimum wages have more adverse consequences when they have the greatest potential benefits – i.e. for low-skilled workers for whom they are effective at raising wages.

- Evidence that minimum wages reduce employment of lower-skilled workers does not imply that minimum wages are the wrong policy choice. However, such evidence would imply that minimum wages in developing countries reflect more of a tradeoff between higher wages and lower employment than what one might conclude from a simple overview of the heterogeneous evidence. Ultimately, we think the wisdom of higher wages in developing countries should hinge more on whether they help raise incomes of low-income families (for more evidence, see Gindling 2018)

References

Belman, D and P J Wolfson (2016), “What does the minimum wage do in developing countries? A review of studies and methodologies”, International Labor Office, Conditions of Work and Employment Series 62.

Broecke, S, A Forti and M Vandeweyer (2017), “The effect of minimum wages on employment in emerging economies: A survey and meta-analysis”, Oxford Development Studies 45(3): 366-391.

Gindling, T H (2018), “Does increasing the minimum wage reduce poverty in developing countries”, IZA World of Labor 30.v2 (on-line).

Harris, J R and M P Todaro (1970), “Migration, unemployment and development: A two-sector analysis”, American Economic Review 60(1): 126-142.

Munguía Corella, L F (2019), “Minimum wages and enforcement effects on employment in developing countries”, Unpublished paper.

Neumark, D and L F Munguía Corella (forthcoming), “Do minimum wages reduce employment in developing countries? A survey and exploration of conflicting evidence”, World Development.