Low-skilled natives tend to be most affected by low-skilled migrants, but are high-skilled natives most affected by high-skilled migrants?

Public debate often expresses fear that immigrants take jobs of natives and increase labour market competition, which causes wages to fall. While this debate is global, the academic literature has concerned itself primarily with immigration to high-income countries, with particular attention given to Mexican immigration to the US. Even though consensus in this literature remains somewhat elusive, we know even less about the labour market impacts of internal migration (migration within the border of one’s own country) in developing countries, even though these migration flows are multiple times larger than those from low to high-income countries (Bell and Charles-Edwards 2013).

Overcoming the challenge of identifying causal effects

The primary econometric concern that has challenged estimates of the impact of migration is that migrants have a tendency to migrate to areas with better labour market opportunities. As a result, simple OLS estimates of labour market impacts of migration are likely biased in the positive direction. In recent work (Kleemans and Magruder 2018), we use an instrumental variable approach to address this issue. We focus on internal migration in Indonesia where we have a rich longitudinal dataset that tracks the place of residence, occupation, and income for almost 29,000 individuals over a 13-year time period. We use empirical migration patterns to form catchment areas of origins that send migrants to each destination district. We then generate exogenous variation in the number of migrants in each district using rainfall shocks in these catchment areas, following Munshi (2003).

Findings: A modest decrease in income and employment

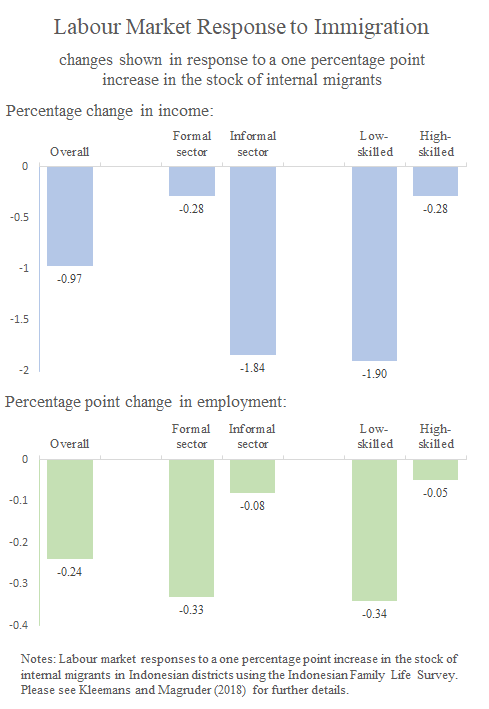

We find that a one percentage point increase in the share of migrants, which is equivalent to a 6% increase compared to baseline migration rates, leads to a modest decrease in income of 0.97% and reduces employment by 0.24 percentage points. We show that, as expected, the negative effects using our instrumental variables approach are larger than OLS estimates. The wage estimates are very similar in magnitude to those reported for the US in Borjas (2003), but the distribution of these effects across sectors and across individuals is quite different as shown graphically in Figure 1.

Labour market effects in countries with a large informal sector

We might anticipate labour market impacts in developing countries to be quite different from those in the US because labour markets are structurally different. The conventional characterisation of developing country labour markets features a heavily regulated formal sector that coexists with an uncovered informal sector, exhibiting lower wages and productivity (e.g. Harris and Todaro 1970). Indeed, the labour market impacts vary strongly by sector: the negative income effects are concentrated in the informal sector, with a 2.11% decrease of informal sector income, and the employment effects are largest in the formal sector at 0.33 percentage points (see Figure 1).

Who is most adversely impacted by immigration, and why?

The literature on migration from Mexico to the US finds that immigration disproportionally affects natives with low levels of education because they are most similar to Mexican immigrants and therefore directly compete for jobs, a phenomenon known as substitutability. Internal migrants in developing countries, however, tend to have higher levels of education than their native counterparts, because the more affluent members of the society have sufficient resources to move (Hicks et al. 2018) and because average educational attainment at the destination is not otherwise so different. Indeed, we find that internal migrants in Indonesia have higher levels of education, are more likely to be employed, and tend to have higher-paying and more secure formal sector jobs compared to natives. In this case, substitutability implies that highly educated natives would be most adversely impacted by immigration, because of their similarity to incoming migrants. Yet, this is not what we find. As shown in Figure 1, it is still the more vulnerable segments of the society with lower levels of education who are most negatively affected and who see their wages go down almost twice as much as those of the general population.

We discuss a number of reasons why poorly educated Indonesians may be disproportionately affected by an influx of highly-educated migrants. We find little evidence that this result could be explained by differences in the returns to skill between migrants and natives, such that highly educated migrants are more substitutable to low-educated natives in terms of skill level. We also do not find support for the hypothesis that this result is driven by differences between average treatment effects of migrants in general and local average treatment effects of weather-induced migrants that we estimate. Instead, we propose that this result may be understood as another consequence of the dual-sector nature of the Indonesian labour market with a wage floor in the formal sector where the less-skilled group faces chances of disemployment from the formal sector, and fiercer wage competition for the more abundant informal sector jobs.

Concluding remarks

These results suggest that context matters in immigration debates. Who gains and loses from immigration will depend on who immigrates, and how those immigrants are integrated into the labour market. These two factors are likely very different in a number of policy-relevant contexts. For example, the skill composition and labour market integration of refugees is likely very different from international immigrants which in turn is likely very different from internal migrants. Simple policies to improve the livelihoods of immigrants, or of the natives who could be displaced by them, may not be effective without a careful consideration of the immigration context.

References

Bell, M and E Charles-Edwards (2013), ‘Cross-national comparisons of internal migration: An update on global patterns and trends’, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Borjas, G (2003), “The labour demand curve is downward sloping: Re-examining the impact of immigration on the labour market,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(4): 1335–74.

Harris, J and M Todaro (1970), “Migration, unemployment and development: A two-sector analysis,” American Economic Review 60(1): 126–42.

Hamory Hicks, J, M Kleemans, N Li, E Miguel (2018), “Re-evaluating agricultural productivity Gaps with longitudinal microdata,” NBER Working Paper.

Kleemans, M and J Magruder (2018), “Labour market responses to immigration: Evidence from internal migration driven by weather shocks,” Economic Journal 128: 2032-2065.

Munshi, K (2003), “Networks in the modern economy: Mexican migrants in the US labour market,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(2): 549–99.