Affording tenants in India property rights on the land they farmed exacerbated son preference, resulting in fewer girls surviving to the age of one

Secure property rights are considered a cornerstone of economic development. Land rights are particularly important in developing countries where large fractions of the population are dependent upon agriculture. Between 1955 and 2000, a billion people and nearly as many hectares were affected by land reform. Previous research demonstrates the importance of land security in increasing agricultural productivity, facilitating access to credit, and in reducing poverty and cross-household asset inequality (Besley and Ghatak 2010, Bardhan et al. 2014). However, very little attention has been devoted to investigating impacts of land reform on gender inequality within the household.

Where land rights are heritable and primarily inherited by sons (Botticini and Siow 2003), land reform may exacerbate son preference. Besides raising land values via productivity improvements, land reform will tend to enhance the inheritance motive for ensuring a male heir. This would be compounded if sons contribute more to cultivating the land than daughters.

In a recent paper (Bhalotra et al. 2018), we study impacts of variation in land rights created by Operation Barga, a tenancy reform in the Indian state of West Bengal that previous research has shown to have increased agricultural productivity and farm incomes significantly (Banerjee et al.2002, Bardhan and Mookherjee 2011). We find that higher programme implementation rates were associated with significantly raised survival chances of boys, especially boys in families in which the first-born child was a girl. This is consistent with primogeniture, as the male-biased inheritance motive no longer operates once a family has a first-born son.

Our findings provide evidence of the role of gender-biased inheritance motive in explaining the ‘missing women’ phenomenon in India, and why it does not abate with economic development. In particular, they highlight unintended consequences of land reform policies in societies exhibiting gender imbalance in property inheritance patterns owing to a combination of traditional norms and inheritance laws.

Data and methods

The land reform programme involved registration of tenant farmers in West Bengal, which endowed them with heritable tenurial security, and capped landlord shares. It was initiated by a Left Front government elected in 1977. It is estimated that 2-3 million sharecropper tenants were registered – comprising between half and two-thirds of all tenants – by the mid-1990s, after which registration plateaued.

We merged district-year data on the sharecropper registration rate in 1977-1991 with the year and district of birth of children in the National Family Health Survey for India (NFHS), which collects fertility histories, including the sex of births and their survival to age one. Using these data, we examined effects of the land reform separately on sex ratios at birth, infant mortality rates, and fertility.

We also utilise a second data set; a farmer-village-household panel survey (VHPS) used by Bardhan and Mookherjee (2011) and Bardhan et al. (2014) to study the impacts of the programme on farm productivity and land inequality. This provides data on proportion of cultivable land registered under Operation Barga at the village rather than district level. It has a finer measure of registration and details of household landholdings but offers only a measure of surviving births by gender and year of birth, which is the net outcome of the sex ratio at birth, gender differences in survival, and fertility.

Results

We identify three principal effects of the tenancy programme, which become discernible once registration reaches 50% of all sharecroppers in a district.

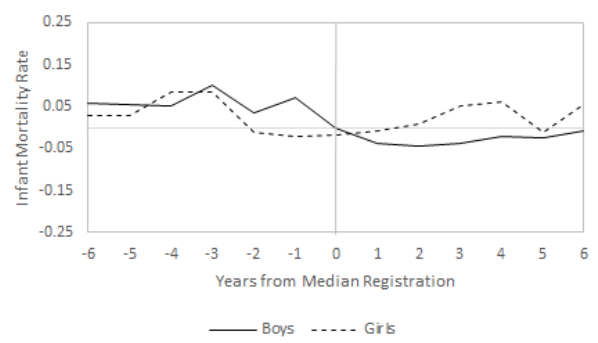

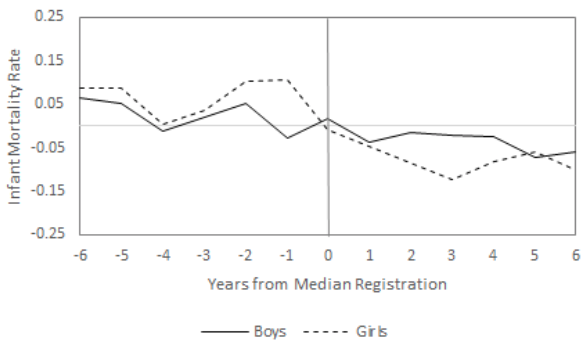

- First, there was a 6.4 percentage point reduction in the infant mortality risk of boys at birth order two or above in Hindu families with a first-born daughter, alongside no change in families with a first son. This indicates that the land reform accentuated the priority accorded by Hindus to ensuring at least one male heir. The mortality risk of girls moved in the opposite direction, showing no change in families in which the first-born was a girl, while exhibiting a six percentage point reduction in families with first sons. This is consistent with previous evidence that wealth effects tend to favour girls, thereby closing the gender gap in mortality risks (e.g. Anukriti 2018, Maccini and Yang 2009). The corresponding estimates for non-Hindu families are smaller and not statistically significant, suggesting that they practice less gender-unequal inheritance practices.

- Second, we find no effects of the land reform on gender differences in the survival chances of first-born children, implying that the gender of the first-born child was effectively random. Previous work confirms this result, by showing balance in a range of characteristics between families with first-born sons and daughters (Anukriti et al.2016).

- Third, we find that the tenancy reform was associated with an increase in the male bias of the sex ratio at birth in Hindu families for second and higher order births, irrespective of the gender of the first-born. Since access to ultrasound facilities was not available in rural West Bengal during the 1980s when land reform was apace, we interpret this as the result of under-reporting of births that survived very short periods, combined with gender bias in these early mortality rates. While the aggregate impact on gender imbalance in reported infant mortality was small (owing to randomness of the gender of the first-born, and opposing effects on the gender gap in infant mortality for families with first born sons versus daughters), the impact of tenancy reform on the sex ratio at birth implies in aggregate an increase of 4-5% in the share of male births.

We additionally find an increase in son-biased fertility stopping after the birth of a second child, which was intensified if the first son was male. This is another expression of an intensified preference for sons following land reform. This was found in both Hindu and non-Hindu families.

The differencing in our specifications between families with first-born sons versus daughters effectively controls for a host of household and community specific variables. Nevertheless, we do not evidence of differential pre-trends, and show robustness of the preceding results to mother or household fixed effects,1 birth year and birth order fixed effects, mother's age at birth, district-specific linear time trends and district-year measures of rice productivity and infrastructure.

Analysis of the second dataset provides corroborating results. We find that an above-median registration rate was associated with a 4.9 percentage point greater probability of boys surviving (to the date of survey) in families in which the oldest surviving child was a girl. This estimate is robust to controls for household fixed effects, land owned prior to the reform, land titles received under a parallel land reform programme, and district-year fixed effects. The differential effects are again significant among Hindu families, but not among non-Hindu families. We additionally find that the documented effects were concentrated among landless households and among small landowners (owning between 1.25 and 2.5 acres of cultivable land). They were plausibly the largest beneficiaries of the programme: the landless owing to gaining secure and heritable cultivation rights to leased land, and the small landowners owing to rising land values.

Figure 1 Infant mortality of Hindu children with first-born sisters

Figure 2 Infant mortality of Hindu children with first-born brothers

Discussion

Using two different datasets with different measures of the rate of tenant registration, we find compelling evidence that it was associated with increased survival of boys relative to girls. The most plausible explanation of this is that gaining land rights that could be passed on to sons led families to attach greater value to having sons. In households that had a son at first birth, we observe larger survival gains for girls, in line with the wealth effects of land reform (which has been shown to raise productivity) favouring girls.

Related research (Almond et al. forthcoming) analyses the Chinese land reform during the late 1970s and, like us, finds child gender ratios became more male-biased after land reform. However, there are differences in the institutional setting and hence in plausible explanations of this result. Under the Chinese reform, the state retained control over land allocation, land rights were not necessarily intergenerationally transferable, and men and women had equal rights in state redistribution of land. Hence male-biased inheritance, which we argue explains the results in India, is unlikely to have driven behaviour in China. Almond et al. argue that income gains from land reform in China raised both the desire to have sons and the feasibility of fulfilling this desire.

Editors’ note: This column has been published in collaboration with Ideas for India.

References

Almond, D, H Li and S Zhang (Forthcoming), “Land Reform and Sex Selection in China”, Journal of Political Economy.

Anukriti, S (2018), “Financial Incentives and the Fertility-Sex Ratio Trade-Off”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics,10(2): 27-57.

Anukriti, S (2018), ‘Financial incentives and the fertility-sex ratio trade-off in India’, Ideas for India, 25 June 2018.

Anukriti,S, S Bhalotraand H Tam (2016), ‘On the Quantity and Quality of Girls: New Evidence on Abortion, Fertility, and Parental Investments’, IZA (Institute of Labor Economics) Discussion Paper No. 10271: October.

Banerjee, A V, P J Gertler and M Ghatak (2002), “Empowerment and Efficiency: Tenancy Reform in West Bengal”, Journal of Political Economy, 110(2): 239–280.

Bardhan, P and D Mookherjee (2011), “Subsidized Farm Input Programs and Agricultural Performance: A Farm-Level Analysis of West Bengal’s Green Revolution, 1982–1995”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3(4): 186–214.

Bardhan, P, M Luca, D Mookherjee, and F Pino (2014): “Evolution of land distribution in West Bengal 1967–2004: Role of land reform and demographic changes,” Journal of Development Economics, 110, 171–190. 27.

Besley, T and M Ghatak (2010): “Property Rights and Economic Development,” in Handbook of Development, ed. by D. Rodrik and M. Rosenzweig, s.n, 4525–4595.

Bhalotra, S, A Chakravarty, D Mookherjee and F J. Pino (2016), ‘Property Rights and Gender Bias: Evidence from Land Reform in West Bengal’, IZA Discussion Paper No. 9930 (forthcoming, American Economic Journal: Applied).

Botticini, M and A Siow (2003), “Why Dowries?”, American Economic Review, 93(4): 1385–1398.

Maccini, S and D Yang (2009), “Under the weather: Health, schooling, and economic consequences of early-life rainfall”, American Economic Review, 99(3): 1006–26.

Endnotes

[1] Fixed-effects help to analyse the impact of variables that vary over time. They explore the relationship between predictor and outcome variables within an entity. Each entity has its own individual characteristics that may or may not influence the predictor variables. Fixed effects remove the effect of those time-invariant characteristics so we can assess the net effect of the predictors on the outcome variable.