The farm size–yields relationship is not informative for improving agricultural productivity among small landholders in developing countries

Among developing and poor countries, agriculture remains the dominant source of livelihood despite low agricultural productivity, with shares of employment in agriculture exceeding 50%. It follows that growth in agricultural productivity is key in promoting structural transformation and fighting poverty and food insecurity. Globally, most of the extreme poor live in rural areas and are engaged in small-scale household farming. In this context, countries and international organisations often focus their attention on land policies targeting smallholder farmers.

Policies aiming to reduce land concentration and foster smallholders are partly supported by a large literature documenting a negative relationship between the land size of farms and their ‘yields’ – a measure of land productivity, defined as output per unit of land. The observation was first noted in the late 1930s by Chayanov (1966) in Russian agriculture, later documented by Sen (1962) for India, and subsequently replicated all around the world, becoming one of the most entrenched stylised facts in development economics (Berry and Cline 1979, Barrett et al. 2010, Foster and Rozensweig 2022).

The inverse relationship between farm size and yields has been interpreted as evidence that small farms are more productive than large farms, with consequential policy implications. If small farms are indeed more productive, then policies that encourage small landholdings (such as land redistribution or land ceilings) could increase aggregate productivity and reduce rural poverty. Such measures are also attractive from a policy perspective, since farm size is easily observable, facilitating the implementation of seemingly productivity-enhancing agricultural policies.

In Aragon, Restuccia, and Rud (2022), we highlight the limitation of using yields as a measure of farm productivity in developing countries, and argue that it leads to a misinterpretation of the relationship between farm size and productivity.

Distinguishing between yields and total factor productivity

We start by distinguishing two alternative measures of productivity. The first measure is farm productivity or ‘total factor productivity’ (TFP), which captures the returns to all factors of production, i.e. the ability of a farmer to produce an amount of output with a given set of inputs – including land, labour, tools, and fertilizers, among others. The second measure, more commonly used in the literature, is ‘yields’, defined as production per unit area of cultivated land.

Yields is a partial measure of productivity. It can increase either when total factor productivity is higher, or when the use of other inputs is higher. In contexts where all inputs are fixed, changes in total and partial productivity due to external reasons (such as temperature or pollution) are the same. However, when other inputs change, these productivity measures would diverge. For example, farmers can increase yields by using more labour in a fixed amount of land. In this case, even if TFP remains the same, a higher land productivity (yields) is attained at the expense of lower labour productivity (with diminishing returns to labour).

Using yields as a measure of productivity leaves greater room for measurement errors

Our research shows that using yields as a proxy for farm productivity can introduce other sources of inaccuracy. If smaller farms have less access to land markets than larger farms, then this can affect their input choice. For example, by inducing small farms to use relatively more labour in production which would increase yields even if a small farm is less productive. Similarly, if the agricultural technology is such that there are decreasing returns to scale to variable inputs, doubling inputs produces less than twice the output. In that case, for two farms with the same TFP, the smaller farm may have higher yields.

These findings imply that the statistical relationship between yields and farm size that researchers have been emphasising would not capture the true relationship between farm productivity and farm size. While TFP is more difficult to obtain, as more detailed data is required to estimate it, it is the measure that matters for policy purposes. In a world with no frictions, we expect high TFP farmers to operate larger farms, just as in other less constrained economic environments, where more productive firms tend to be larger.

The relationship between farm size, yield, and TFP in Uganda

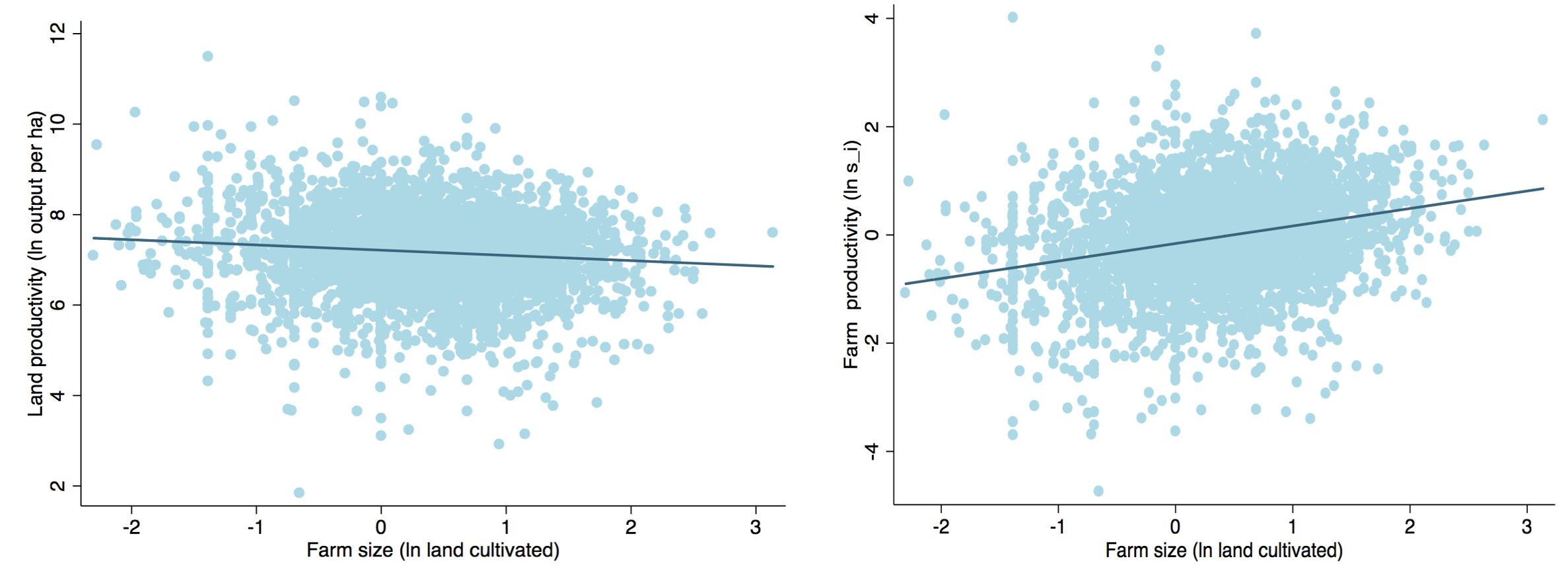

Using rich data from four waves of a survey that follows more than 4,000 farming households in Uganda over time, we estimate a measure of farm-level TFP and find that when using this measure instead of yields, the size–productivity relationship turns positive (see Figure 1). Larger farms are on average more productive than smaller farms, even though their yield is lower. These results hold when we consider different characteristics of the farms, and when we use GPS measures of land (a more accurate measure of land input), rather than farmer self-reported variables. Interestingly, when we apply the same methods to data from Tanzania, Bangladesh, and Peru, the results show the same pattern.

Figure 1 Land productivity (yield), farm productivity (TFP), and farm size

Notes: The panel on the left graphs farm productivity, using yields (per hectare), on the vertical axis and farm size on the horizontal axis. Consistent with the literature, a slight inverse relationship is seen. The panel on the right graphs TFP on the vertical axis and farm size on the horizontal axis, for the same farms, and finds instead a positive relationship between productivity and farm size.

While more productive farms operate more land, the land allocation is still far from that implied by an efficient allocation of land across farmers, consistent with a literature emphasising misallocation in agriculture in poor and developing countries (Adamopoulos and Restuccia 2014, Restuccia and Santaeulalia-Llopis 2017, Adamopoulos et al. 2021). In this context, we also find that the positive relationship between farm size and productivity is stronger for households (farms) that own their land, as opposed to households holding customary rights over their land. In the context of Uganda, customary land tenure may prevent households to pledge or sell land as easily as freeholders. This suggests that market distortions play an important role in the allocation of land and that the productivity of the agricultural sector in developing countries would benefit from stronger land property rights.

How informative is the size–productivity relationship?

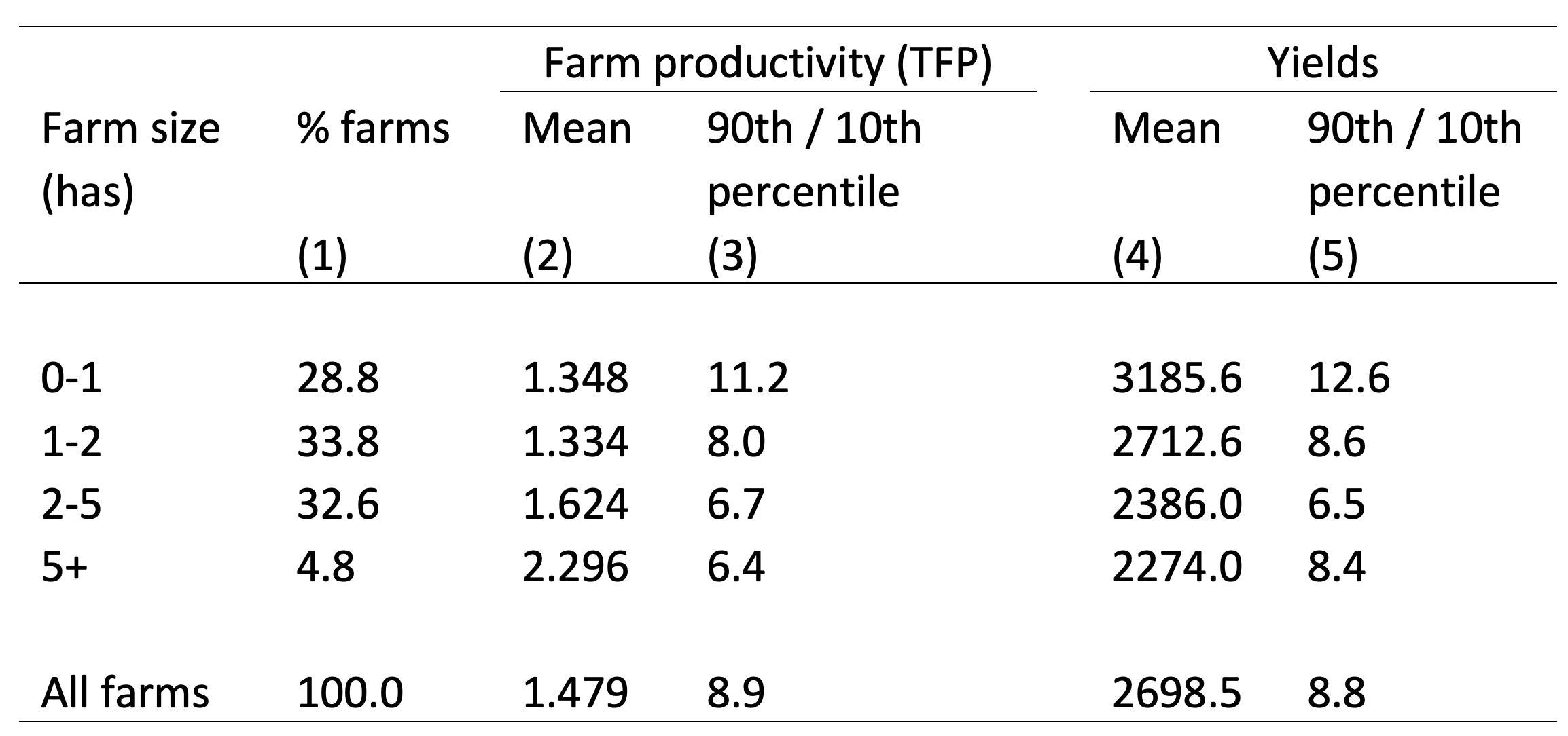

The detailed data reveal a substantial amount of dispersion in both measures of productivity for farms of the same size category, a dispersion that is similar in magnitude to the differences in productivity across farms of different sizes (see Table 1). This finding implies that policies using farm size as proxy for productivity targeting are likely to be ineffective. This may explain why prevalent policies in developing countries that aimed to improve productivity by targeting farm size have often failed to deliver positive results; see, for example, the case of land ceilings and government intervention in the redistribution of land in Philippines in 1980s (Adamopoulos and Restuccia 2020).

Table 1 Productivity dispersion by farm size

Notes: Farm size calculated using average area planted. Farm productivity is farm TFP and Yields is the average land productivity of each farm.

Policies must focus on farm productivity, not farm size

Our results indicate that there is no simple policy instrument to improve agricultural productivity and address rural poverty and food security. An effective policy should facilitate better resource allocation by farm productivity. The problem is that productivity is difficult to observe for the policymaker. For that reason, policy should focus on fostering and improving markets, in particular markets for land that facilitate the flow of resources to more productive uses.

Policies that secure and enforce land ownership and user rights may be an important step forward in the development of better functioning markets. Even with an egalitarian distribution of property rights, which may satisfy other objectives (cultural or political), land ownership can be decoupled from farm operational scales through rental markets or other decentralised mechanisms. Decoupling land use from land rights can also have substantial effects on the economic decisions of farmers, including migration, sector of occupation, and mechanisation or other technology adoption, further contributing to productivity growth in agriculture (de Janvry et al. 2015, Adamopoulos et al. 2021).

References

Adamopoulos, T, and D Restuccia (2014), "The size distribution of farms and international productivity differences", American Economic Review 104(6): 1667-97.

Adamopoulos, T, and D Restuccia. 2020. "Land Reform and Productivity: A Quantitative Analysis with Micro Data", American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 12(3): 1-39.

Adamopoulos, T, L Brandt, J Leight, and D Restuccia (forthcoming), "Misallocation, selection and productivity: A quantitative analysis with panel data from China", Econometrica.

Aragon, F, D Restuccia, and J P Rud (2022), "Are small farms really more productive than large farms?", Food Policy 106: 102-168.

Barrett, C, M Bellemare, and J Hou (2010), "Reconsidering conventional explanations of the inverse productivity-size relationship", World Development 38(1): 88-97.

Berry, R and W Cline (1979), Agrarian Structure and Productivity in Developing Countries, Johns Hopkins University Press.

Chayanov, A (1966), The theory of peasant economy, Richard Irwin.

De Janvry, A, K Emerick, M Gonzalez-Navarro, and E Sadoulet (2015), "Delinking land rights from land use: Certification and migration in Mexico", American Economic Review 105(10): 3125-49.

Foster, A and M Rosenzweig (2022), "Are there too many farms in the world? Labour-market transaction costs, machine capacities and optimal farm size", Journal of Political Economy 130(3).

Restuccia, D and R Santaeulalia-Llopis (2017), "Land misallocation and productivity," NBER Working Paper No. 23128.

Sen, A (1962), "An aspect of Indian agriculture", Economic Weekly 14(4-6): 243-246.