Income increases for international migrants from the Philippines fostered economic development and investments in education in migrant-origin communities.

While there is ample evidence that international migration raises incomes for the migrants themselves (Clemens et al. 2019, Mobarak et al. 2023, Naidu et al. 2023), evidence is scarce on how international migrant income affects development outcomes in the areas from which migrants originate. On the one hand, migrant income can lessen cash flow problems and lead to increased educational and entrepreneurial investments (Yang 2008). Increased spending in origin communities, through remittances, can further stimulate the origin economy, also benefitting households without migrants. On the other hand, a common concern surrounding international migration is that better migration opportunities might lead to ‘brain drain’, with negative development impacts (Docquier et al. 2007). Evidence pointing to one of these possibilities would be informative about whether migration policy could play a prominent role in efforts to reduce global poverty.

The Philippines is a major source of international migrants

We study how persistent increases in international migrant income affect long-run economic development in migrant-origin areas. We do so in the context of one of the largest origin countries for migrant labour, the Philippines. The Philippines presents an ideal context to study this question, as:

- International migration is exceedingly common in the Philippines, with one-fourth of households reporting that they receive migrant remittances.

- Filipino migrants migrate to a diverse set of destination countries, which is crucial for the identification of causal impacts in our setting.

- The regulated nature of migration leads to high-quality data that facilitates precise measurement.

However, the Philippines is not unique in regulating and facilitating labour migration. Motivated by the substantial income gains that accompany international migration, many developing countries facilitate citizens’ international migration. In fact, of 70 developing countries with a population exceeding a million, over 88% have a dedicated government agency for overseas employment and diaspora engagement, and 78% have policies promoting migrant remittances (United Nations 2019).

Unique international labour migration data in the Philippines

We combine novel administrative data on migrant contracts from the Philippines Overseas Employment Agency with household surveys and Census microdata. The Philippines Overseas Employment Agency data includes the migrant’s destination country, earnings, and province of origin. This granular data allows us to tie migration episodes to specific provinces and, therefore, measure migrant income at the province level. Further, the ability to form dyadic province-destination country pairs provides the foundation for our causal identification strategy, as we discuss further below. Household survey and census data provide province-level measures of income, consumption, and educational attainment. Combining this data allows us to study the impacts on province level global income per capita - defined as the sum of its domestic income and (international) migrant income per capita - and its international and domestic income components over roughly two decades after the migrant income shock took place in 1997.

The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis was a shock to international migrant income

To isolate the causal relationship between migrant income and development in their home countries, we combine changes in relative exchange rates driven by the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis with the varying migration ties of Filipino provinces to different migrant destination countries.

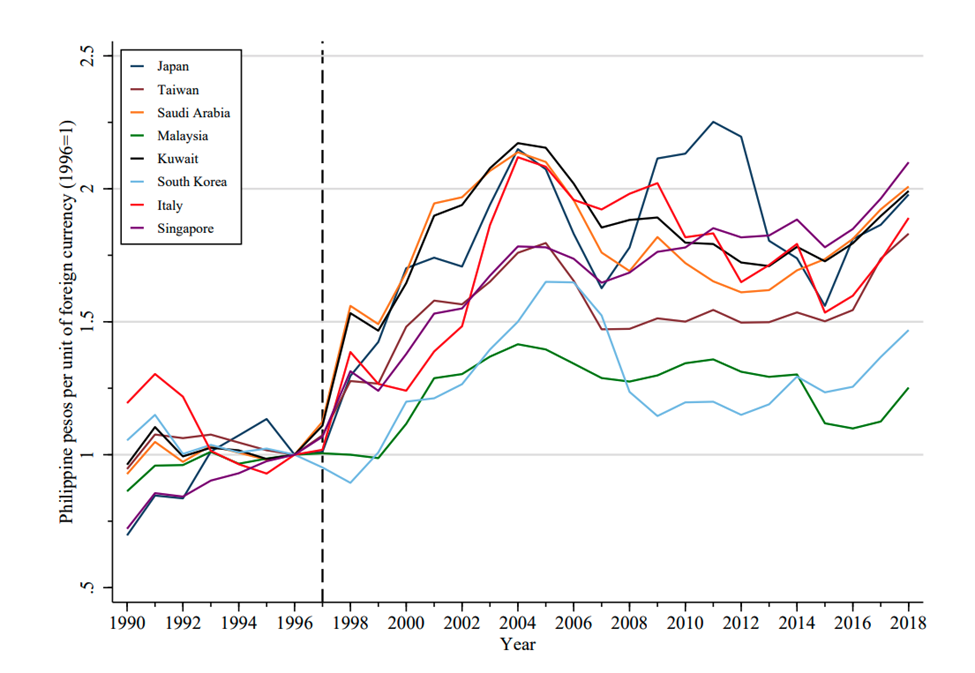

Figure 1

Figure 1 illustrates how the various destinations for different Filipino migrants saw differing changes to their relative exchange rates. These exchange rate movements were persistent over the following two decades. Further, Filipino provinces vary greatly in terms of how much of their migrant income is from different destination countries. For example, baseline migrant income from Japan is 10.7 times higher on a per capita basis for the province of Bulacan as opposed to Leyte province. Japan’s exchange rate shock, therefore, should have a greater impact on population-level outcomes in Bulacan than in Leyte. We generate a province-level migrant income shock measure based on this intuition.

Migrant income leads to long-run income and consumption increases in origin areas

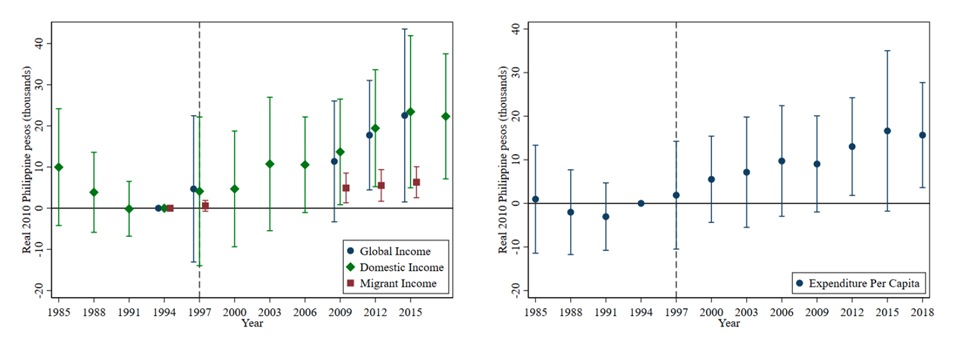

We find that the persistent migrant income shock after the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis leads to significant increases in both per-capita migrant income and per-capita domestic income (income earned in the Philippines) over two decades. The left panel of Figure 2 presents the corresponding event study results.

Figure 2

While the initial migrant income shocks led to increases in both migrant and domestic income, over 75% of the increase in a province’s per capita global income is driven by effects on domestic income. This is a novel finding in the development literature: while an exogenous increase in migrant earnings opportunities leads to income gains from both domestic and international sources, over the course of two decades, the domestic income gains actually come to dwarf the international income gains.

The large impact on domestic income is driven by increases in both wage income and entrepreneurial income, suggesting broad development impacts on origin economies. Overall, a 1 standard deviation migrant income shock increases per capita domestic income by 1,750 Philippine pesos over two decades, which corresponds to 6.7% of mean per capita domestic income in 1994. These gains in domestic and global income are also reflected in increases in per capita household consumption in origin provinces, as shown in the right panel of Figure 2.

The increase in migrant income not only reflects the mechanical impact of the exchange rate shifts but is also driven by an increase in overseas income per migrant and an increase in the skilled overseas migration rate. Combined, the higher participation and better performance in overseas labour markets led to migrant income gains that are substantially magnified compared to the initial shock itself. Overall, a 1 standard deviation migrant income shock increases per capita migrant income by 523 Philippine pesos over two decades, which corresponds to 12.7% of mean per capita migrant income in 1994.

A quarter of the long-run income gains are due to increased educational investments

Given the central role of human capital accumulation for development, and long-standing debates on whether migration leads to brain drain or brain gain, we also empirically estimate the impact on origin educational attainment. We find large positive impacts on the share of the working-age population with secondary schooling and college. Further, the share of overseas migrants with a college education also responds positively to the shock.

How much of the long-run impact of the migrant income shock on both domestic and migrant income is due to increased educational attainment? There are two key pathways from educational attainment to increased global income. First, educated workers earn more domestically. Second, better-educated individuals both have higher international migration rates, and they work in higher-skilled overseas occupations.

To quantify the role of educational investments on the income gains, we build and estimate a simple model of international migration with differing skill levels. The model implies that about 23% of the domestic income gains and 24% of migrant income gains are due to educational investment, suggesting that approximately a quarter of the total long-run income gains are realised through educational gains.

Migration policy should be a tool in the development policy toolkit

Our findings suggest that international migration not only offers potentially high pecuniary returns for the migrants themselves, but also leads to longer-run development of migrant-origin areas. This is not only manifested in increased domestic earnings in response to migrant income shocks, but also in increased educational outcomes for the origin populations, which can lead to higher economic growth in the long run. That migrant income can lead to increased educational investment through potentially relaxing liquidity constraints or increasing returns to education suggests that simplistic accounts of how migration leads to brain drain for the origin-area may miss sizable dynamic gains over time. Overall, migration policy should be considered as an important part of the development policy toolkit.

References

Abarcar, P., and Theoharides, C. (2024), "Medical Worker Migration and Origin-Country Human Capital: Evidence from U.S. Visa Policy," Review of Economics and Statistics, 106(1): 20-25.

Clemens, M. A., Montenegro, C. E., and Pritchett, L. (2019), "The Place Premium: Bounding the Price Equivalent of Migration Barriers," The Review of Economics and Statistics, 101(2): 201–213.

Docquier, F., Lohest, O., and Marfouk, A. (2007), "Brain Drain in Developing Countries," The World Bank Economic Review, 21(2): 193–218.

Mobarak, A. M., Sharif, I., and Shrestha, M. (2023), "Returns to International Migration: Evidence from a Bangladesh-Malaysia Visa Lottery," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 15(4): 353–388.

Naidu, S., Nyarko, Y., and Wang, S. (2023), "The Benefits and Costs of Guest Worker Programs: Experimental Evidence from the India-UAE Migration Corridor," NBER Working Papers, No. 31354.

United Nations (2019), "World Population Policies 2019: International Migration Policies and Programs," Technical report, United Nations.

Yang, D. (2008), "International Migration, Remittances and Household Investment: Evidence from Philippine Migrants’ Exchange Rate Shocks," The Economic Journal, 118: 591–630.