Civil society oversight can curb corruption in public infrastructure development, when supported by the relevant anti-corruption authority

Lava Jato, or ‘Operation Car Wash’, began in early 2014 and is a striking reminder of Latin America’s corruption problem. A team of Brazilian prosecutors found that Odebrecht and other construction firms had been colluding to ensure that the state awarded them infrastructure contracts at inflated prices (Smith et al. 2015, Fuentes 2016, Lagunes 2018). It was later discovered that bribes paid by Odebrecht extended beyond Brazil’s borders. In his plea-bargain testimony, the then-CEO of Odebrecht admitted that his company had bribed politicians in multiple countries, including Peru (Pressly 2018). All told, Odebrecht paid nearly $800 million in bribes to secure government contracts across Latin America (Smith et al. 2017). A subway line in Lima was one project, among several, whose contracts are suspected of having been awarded on the basis of bribes (Agencia DPA 2018).

A field experiment in Peru

Responding to the concerns raised from corruption in Latin America, I executed a field experiment in Peru to test the extent to which civil society oversight can curb corruption and inefficiency in public infrastructure, when its efforts are supported by the relevant authority. The study shows that municipalities that received anti-corruption monitoring executed their public infrastructure at a normal rate. Importantly, they also executed their public infrastructure at a lower cost than similar municipalities that did not receive the anti-corruption monitoring. In other words, the monitoring intervention caused overall efficiency gains. Figure 1 shows images captured using Google Earth of public infrastructure pre- and post-treatment.

Figure 1 Before and after: Images of public infrastructure that received the monitoring intervention

Corruption and inefficiency in public infrastructure

There are reasons why this study, which focuses on corruption, also raises the issue of inefficiency. For one, corruption and inefficiency are related pathologies. A bureaucracy that is affected by one is likely also affected by the other. Indeed, there is empirical evidence that corruption and inefficiency are strongly correlated (Dal Bó and Rossi 2007). There is also evidence that bureaucratic delays incentivise bribery (Mauro 1995), which serves to show that corruption and inefficiency are mutually reinforcing. This likely explains why anti-corruption agencies, including the one featured in this study, uphold the mandate of fighting both corruption and inefficiency.

One of the areas where corruption and inefficiency can have the greatest negative impact is in the construction of public infrastructure. Communities lacking in infrastructure are disconnected from the rest of the world, finding it difficult to attract investment and promote economic development (Sachs et al. 2004). Aware of this, the United Nations (2016) included infrastructure investment among its priorities for sustainable development.1

However, ensuring that communities in the developing world have universal access to basic infrastructure requires contending with corruption and inefficiency. Transparency International (2008, 2011) finds that public infrastructure is one of the sectors with the highest corruption vulnerability. Corruption can target a public infrastructure project at any of five stages, including procurement and construction (Wells 2014). In the construction stage, developers can scheme to increase the contract sum in an attempt to capture greater profits or recover whatever was paid in bribes during the procurement stage (Wells 2014).

A key reason why infrastructure is especially prone to corruption is that it is difficult to standardise the cost of projects (Collier and Hoeffler 2005). This lack of standardisation, in turn, allows developers and government officials to take advantage of the taxpaying public’s ignorance about the appropriate cost of infrastructure development.

Curbing corruption with civil society oversight

Following this logic, a solution to the problem of corruption in public infrastructure could require that citizens receive more and better information about public infrastructure development. However, the members of the public dedicate a majority of their time to private affairs and are often confused, if not repelled, by the complexities of government. The illiteracy and poverty found in the developing world only adds to this challenge. Considering the limitations that beset citizen oversight, what if, instead, the effort focused on empowering organised civil society to monitor the execution of public infrastructure?

Collaboration between civil society and an anti-corruption authority

The study assumes that civil society organisations (CSOs) have many of the resources, including the know-how, needed to detect corruption, but beyond public naming and shaming they lack the capacity to sanction wrongdoing. Thus, it is important that the authorities who do have the capacity to punish wrongdoers support the work of CSOs.

To test the effect of a one-two punch delivered by a CSO and an anti-corruption authority, I generated a formal collaboration with two key organisations. The first is a reputable non-governmental organisation with nearly fifteen years of experience promoting ethical conduct in public administration. The second is Peru’s agency responsible for auditing, evaluating, and investigating all government activities.

Thus, two major national anti-corruption forces – one hailing from civil society and the other from the public sector – came together for the purpose of monitoring public infrastructure. Half of the municipalities in the sample were randomly selected to enter into a control group. These local governments were left untouched by the study’s intervention. In contrast, the other half received letters from the collaborating CSO and from the national anti-corruption agency. These letters announced that specific infrastructure projects under the municipal governments’ charge were being monitored.

The impact

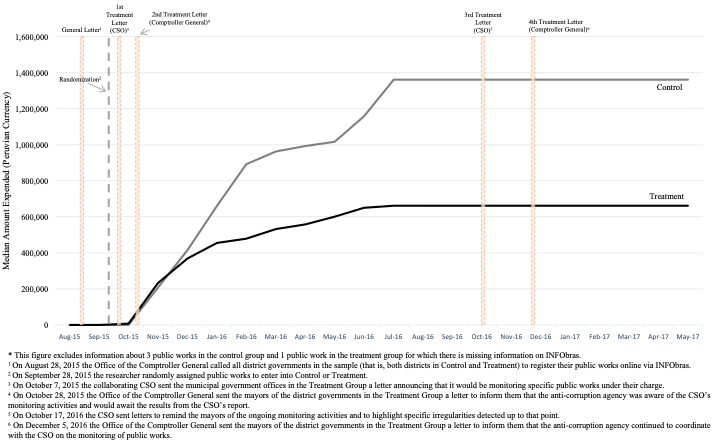

It is noteworthy that the field experiment’s results show that, on average, the municipalities that received the monitoring intervention spent an estimated 297,900 soles (approximately $91,000) less per project. Stated differently, the monitoring intervention resulted in a 15.05% decrease in the cost of infrastructure development. As illustrated by Figure 2, the monitoring scheme worked.

Figure 2 Month-by-month reporting: Median amount expended on public works (N=196)

Policy implications

The results highlight that civil society oversight can curb corruption and inefficiency in public infrastructure development, when supported by the relevant authority. Municipalities that received the monitoring intervention did not experience time delays and also spent considerably less per project. This shows that anti-corruption agencies can work with CSOs to form effective partnerships that will help tackle the widespread corruption and inefficiency in public infrastructure, nowhere more so than in Latin America.

References

Agencia DPA (2018), "Testigo: Odebrecht pagó más de US$ 24 millones por metro de Lima", El Comercio, 5 October.

Collier, P and A Hoeffler (2005), "The economic costs of corruption in infrastructure", in Global Corruption Report: Corruption in construction and post-conflict reconstruction, Pluto Press.

Dal Bó, E and M Rossi (2007), "Corruption and inefficiency: Theory and evidence from electric utilities", Journal of Public Economics 91: 939.

Fuentes, E (2016), Understanding the Petrobras scandal, Council on Hemispheric Affairs.

Lagunes, P (2018), Backgrounder on Lava Jato, Centre on Global Economic Governance at the School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University.

Mauro, P (1995), "Corruption and growth", Quarterly of Journal of Economics 110: 681-712.

Pressly, L (2018), "The largest foreign bribery case in history", BBC News, 22 April.

Sachs, J, J McArthur, G Schmidt-Traub, M Kruk, C Bahadur, M Faye and G McCord (2004), "Ending Africa's poverty trap", Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1: 117-240.

Smith, M, S Valle and S Blake (2017), "No one has ever made a corruption machine like this one", Bloomberg Businessweek.

Smith, M, S Valle and B Schmidt (2015). "The Betrayal of Brazil", Bloomberg, 8 May 8.

Transparency International (2008), Bribe Payers Index, Transparency International.

Transparency International (2011), Bribe Payers Index, Transparency International.

Wells, J (2014), "Corruption and collusion in construction: A view from the industry", Eds. T Søreide, T and A Williams (eds), Corruption, grabbing and development, Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 23-34.