Conditional transfers in childhood improve education, labour, and economic outcomes in adulthood, especially for women

Cash transfers have become an increasingly popular anti-poverty tool in the developing world. This has seen the uptake of this foundational approach to social protection around the world: India is gradually replacing its Public Distribution System (PDS), which delivers food and other goods to the poor, with monetary transfers. In East Africa, the charity, Give Directly has distributed millions of dollars directly to the mobile bank accounts of poor farmers in Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda. Conditional cash transfer (CCT) programmes that pay parents on the condition that their children attend school (as well as other forms of human capital investment), have thrived in Brazil and Mexico for over two decades, inspiring similar programmes throughout Latin America and beyond.

The short- and long-term effects of cash transfers

A large body of research documents the short-term success of these programmes, often using experimental designs. For example, in Kenya, a year-long randomised trial of Give Directly found that the programme’s unconditional payments raised psychological wellbeing and food security (Haushofer and Shapiro 2018).

Mexico’s CCT programme, Progresa (later known as Oportunidades and now as Prospera), increased schooling enrolment and attendance in its initial 18-month randomised evaluation (Parker and Todd 2017). However, less is known about effects at horizons lasting more than a few years (Blattman et al. 2017). Questions about the longer-term dynamics are only beginning to be addressed and they are causing much debate in the blogosphere and on Twitter.

The long-term effect of conditionalities

These longer-term questions are especially important for CCTs, since the conditionality is specifically designed to improve the lives of the next generation. While unconditional transfers may be sufficient to fight present poverty, requiring investment in children’s human capital is thought to potentially reduce poverty in the future: when children grow up and enter the labour market with greater skills. Testing this proposition is crucial for justifying CCTs.

Evaluating the long-term effects on individuals exposed to CCTs in childhood is fraught with difficulty. In many parts of the developing world, high rates of migration, both within and across international borders, make longitudinal tracking of experimental samples expensive and complicated. Many experimental evaluations of CCT programmes are short-lived, with small differences in exposure between treatment and control groups.

In the case of Progresa’s well-known randomised evaluation, control communities started receiving benefits approximately 18 months after treatment communities. This small difference presents a hurdle to estimating the overall effect of being exposed to the programme in childhood, a more useful comparison than estimating the differential effect of being exposed for slightly longer.

Determining the long-term effects of Mexico’s Progresa

1. Research design

In our research (Parker and Vogl 2018), we overcome these challenges by estimating the long-run impacts of Progresa with a quasi-experimental approach that uses census data on adult outcomes linked to administrative data on programme rollout during childhood. We compare early beneficiaries to a slightly older group that was too old at rollout to reap the programme’s educational benefits, across municipalities with varying rollout timing.

Earlier studies based on the randomised evaluation found that exposure to Progresa during the transition from primary to secondary school — when many students drop out — is key to increasing school enrolment (Behrman, Sengupta, and Todd 2005). We thus compare youth aged 7-11 (pre-transition) with youth aged 15-19 (post-transition) at the onset of rollout, in areas where rollout was more concentrated in the early years of the programme (1997-1999) versus areas where rollout was more concentrated in later years of the programme (2001-2005). Therefore, these age groups are revealing because the 15-19 year olds were too old to reap the central benefits of the programme in both areas, while the 7-11 year olds were young enough to benefit in early rollout areas, but mostly too old to benefit in later rollout areas.

2. Data challenges

Our sample from the 2010 Mexican census includes nearly 700,000 individuals who were aged 7-11 or 15-19 at the start of Progresa. The research design amounts to asking whether the area with earlier rollout saw improvements in lifetime outcomes for earlier cohorts of children, for two areas with the same share of households taking part in the programme.

Our approach enables us to study a sustained difference in programme exposure, and also to study a nationwide programme at scale. It also allows us to move away from the original evaluation sample, for which long-run follow-up is complicated by migration. The sample size of the most affected individuals is small, and selected communities may not be nationally representative.

Muralidharan and Niehaus (2017) highlight issues like these in their recent proposal that randomised evaluations of government programmes be run at scale. They contend that larger-scale evaluations are more likely to deliver representative estimates of large-scale programme impacts. Although they apply this argument to the design of prospective experiments, it raises interesting questions about a trade-off that arises in the long-term follow-up of programmes that were initially evaluated with a small-scale experiment: Should researchers restrict their analyses to the original experimental cohort, or should they look for quasi-experiments that can shed light on a broader sample? We posit that these two approaches are complementary.

The findings: Gendered education, labour market, and household economic outcomes

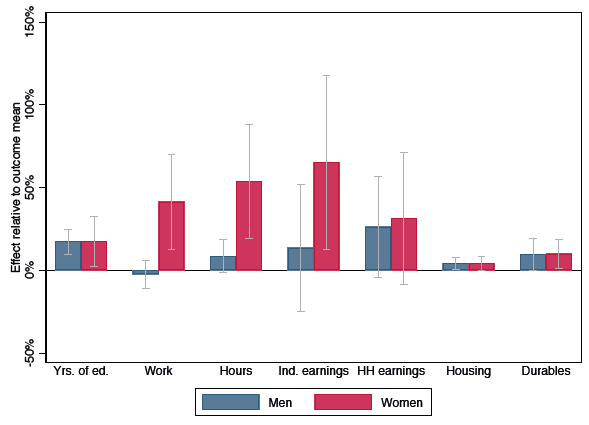

Figure 1 Effects of childhood exposure to Progresa on education and labour market outcomes

Note: The figure displays difference-in-difference estimates of the effect of growing up in a fully treated municipality, divided by the sex-specific outcome mean. Capped spikes are 95% confidence intervals based on bootstrapped standard errors. (See Parker and Vogl 2018 for more details.)

Key findings are shown in Figure 1, which plots the proportional effects of enrolling all households in a municipality before a resident child reaches age 12, with 95% confidence intervals, revealing the following:

Education

- Complete rollout before age 12 improves accumulated education, labour market outcomes, and household economic outcomes in early adulthood, especially for women.

- Educational attainment increases by roughly 1⅓ years for both genders, or 17% of mean attainment.

Labour market

- Labour market effects are more pronounced for women: Childhood Progresa exposure raises women’s probability of working by 41% (11 percentage points), women’s labour hours by 54% (6 hours per week), and women’s labour earnings by 65% (nearly US$40 per month).

- Despite the lack of statistical significance on labour income for men in Figure 1, we do find that childhood Progresa exposure leads men to work in higher paying sectors and increases the probability of having health insurance as a job benefit by more than 50%.

Household economic outcomes

- Household economic outcomes improve for both genders.

- Household ownership of durable goods enumerated in the census increases 10% for both genders.

- Improved housing conditions increases 4%, although some of these effects are only statistically significant at the 10 % level.

- Marginally significant increases in total household labour income are also visible for both genders.

- The gender parity in household-level effects reflects the tendency of early beneficiaries to marry other early beneficiaries, as well as the tendency of young Mexican adults to live with their parents, who were the direct recipients of the cash transfers.

Mechanisms behind the labour market effects

Education

Education likely plays an important role, as a key distinction between the 7-11 year olds and the 15-19 year olds is that the former were young enough to stay in school when the programme rolled out.

Migration

We also find that internal migration may contribute to the labour market effects. Among both men and women, early beneficiaries have higher rates of urban residence and cross-municipal migration. These results suggest a possible causal chain in which Progresa raised educational attainment, which led affected youth to move to more urban areas in search of labour market opportunities.

Implications

These results suggest important positive effects of CCTs on education and labour market outcomes for men and women. Our findings are quite encouraging for proponents of CCTs, as they suggest that youth exposed to CCT programmes may reap benefits throughout their working lives, long after their parents stop receiving cash transfers.

While more evidence is needed, unconditional cash transfer programmes appear to have lower effects on youth education and therefore may have smaller effects on poverty for the next generation compared to CCTs. Our results suggest that government-run CCT programmes, like Progresa, are living up to their promise to lift up the next generation.

Editor's note: An earlier version of this column appeared on VoxEU.org.

References

Blattman, C, Faye, M, Karlan, D, Niehaus, P and Udry, C (2017), "Cash as Capital", Stanford Social Innovation Review, Summer.

Behrman, J, Sengupta, P and Todd, P (2005), "Progressing through PROGRESA: An Impact Assessment of a School Subsidy Experiment in Rural Mexico", Economic Development and Cultural Change, 54(1): 237-275.

Haushofer, J and Shapiro, J (2016). “The Short-Term Impact of Unconditional Cash Transfers to the Poor: Experimental Evidence from Kenya”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(4): 1973-2042.

Muralidharan, K and Niehaus, P (2017). “Experimentation at Scale”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(4): 103-24.

Parker, S and Todd, P (2017). “Conditional Cash Transfers: The Case of Progresa/Oportunidades”, Journal of Economic Literature, 55(3): 866-915.

Parker, S and Vogl, V (2018). “Do Conditional Cash Transfers Improve Economic Outcomes in the Next Generation? Evidence from Mexico”, NBER Working Paper 24303 (latest version available here).