New export opportunities led to a rise in hiring of female white-collar workers through changes in the use of technology and a correction of discrimination amongst Chilean firms.

Editor’s Note: Check out our VoxDevLit to learn more about female labour force participation and trade.

The gender gap in employment stifles economic progress and long-run growth (Lagerlof

2003). According to the International Labour Organization (ILO 2018), only 47% of women aged 15 and older, compared to 80% of men, participated in the labour force in Latin American countries. A host of Latin American countries started to participate in the global market, especially from the 1990s onward. Therefore, it is imperative to understand whether and how such trade policy changes can contribute to enhancing gender convergence in employment, an aspect which is relatively under-researched due to a paucity of data (Goldberg and Pavcnik 2018). In our recent research (Banerjee et al. 2024), we explore how a Free Trade Agreement (FTA), signed between Chile and Mexico in July 1998 that came into force in August 1999, affected the gender gap in employment for Chilean manufacturing firms.

Three features drive our choice in studying this FTA:

- Following the debt crisis of the 1980s, many Latin American countries adopted the export-led development strategy by signing new economic cooperation and trade agreements, and Chile was the leader among them.

- The agreement with Mexico was among the earliest major trade agreements signed by Chile.

- This FTA led to the highest increase in exports (> 200%) for Chile to any single country till 2007. The average tariff on Chilean exports dropped from 14% to zero.

Furthermore, Chile provides an interesting study case because of its diverse manufacturing sector and severe gender employment gap at 23.2% and wage gap at 20.4% in 2020 (INE 2022).

How did the Chile-Mexico Free Trade Agreement affect employment across genders?

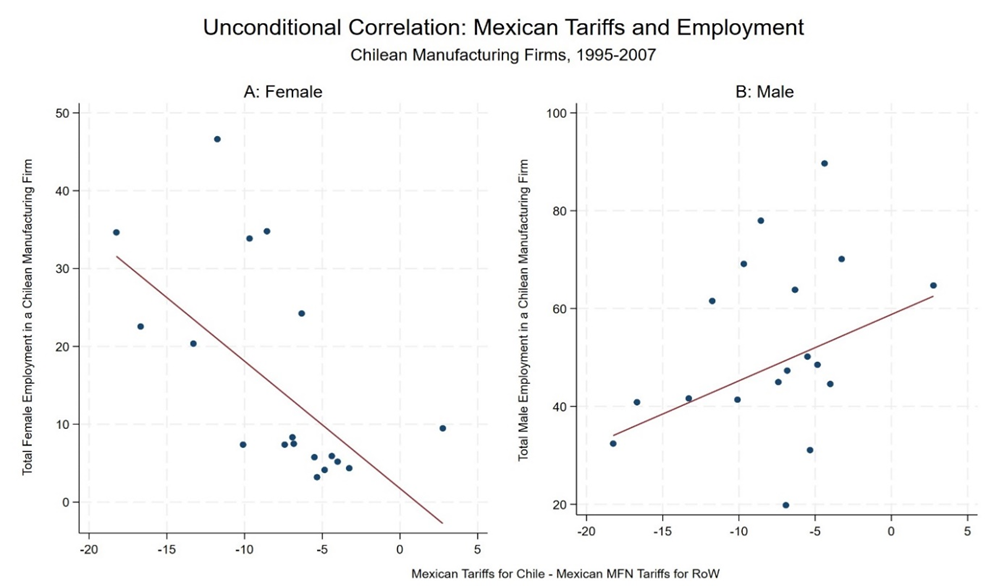

We motivate our analysis with a simple graph on how the FTA affected employment, especially for women. Panel A (Panel B) of Figure 1 presents an unconditional correlation between the total number of female employees (male employees) in an average Chilean manufacturing firm and Mexican tariffs on Chilean goods. We find opposite effects of tariff changes for female and male employment: the lower tariffs on Chilean exports the higher (lower) is the female (male) employment for an average Chilean manufacturing firm.

Figure 1: Chile-Mexico FTA and employment, Chilean manufacturing firms, 1995–2007

Notes: The figure plots the unconditional correlation (non-parametric) between tariff rates for Mexico imposed on Chilean exports and total female employment of a firm. We define the tariff change as: Chile – Mexico FTA Tariffsj = ln(1 + Mexico Tariff in industry “j” on Chilean exports) – ln(1 + Mexico tariff in industry “j” on exports from Rest of the World) The data are divided into 20 bins of each variable.

Which type of exporters explain the gendered impact of trade in Chile?

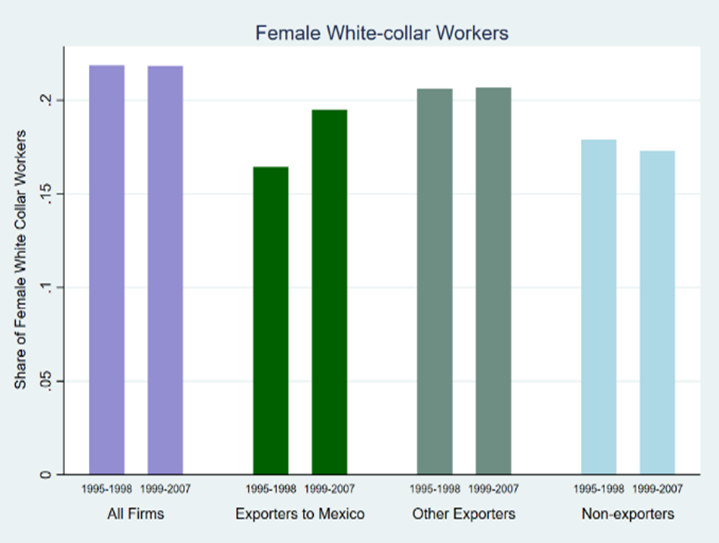

Next, to understand which type(s) of firms are driving our observation we match our firm level data with customs data that has detailed information on export value by each destination to which a firm exports. Figure 2 plots the share of female white-collar workers (including CEOs, owners and skilled workers) for four different types of firms: (a) all firms, (b) exporters to Mexico, (c) other exporters, and (d) non-exporters. The figure clearly shows that the share of female white-collar workers only increased for firms that export to Mexico after the Chile-Mexico FTA. This increase for exporters exporting to Mexico is accompanied by a simultaneous decrease for the non-exporting firms.

Figure 2: Chile-Mexico FTA and female white-collar workers: by exporter type, Chilean manufacturing firms, 1995–2007

Notes: Figure plots the average share of female white-collar workers (female white-collar/total white-collar) according to different types of exporters for the period 1995–1998 and 1999–2007

These stylised facts motivate our empirical investigation which estimates the impact of the FTA on employment. We look at both white- and blue-collar workers.

Female white-collar employment increased for new exporters following a reduction in tariffs to Mexico

Our estimates reveal that a 10% drop in tariffs after the trade agreement increased the share and number of female white-collar workers for a new exporter exporting to Mexico (i.e. firm that starts exporting to Mexico after the FTA) by 1% and 2.9% respectively when compared to an incumbent exporter to Mexico. In other words, the Chile-Mexico FTA, which eliminated tariffs led to about 10% increase in the share of female white-collar workers for a new Chilean manufacturing exporter exporting to Mexico. We also find an overall increase in female employment (both number and share).

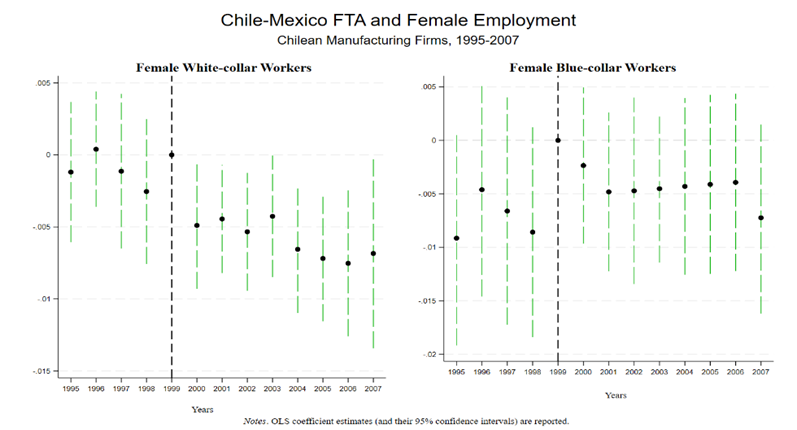

Panel A of Figure 3 plots the evolution of the share of female white-collar employment for new Mexican exporters relative to other exporters. This shows that the drop in tariffs significantly increased the share of female white-collar employment (the coefficients are negative and significant) – the share started to increase significantly from 2000 onward.

Why is there a substitution towards female white-collar workers following the FTA?

This increase in the share of female white-collar workers is primarily driven by an increase in the employment of skilled workers. In particular, we find a substitution effect from male to female in this category of worker (as seen in Figure 1). As a result, the female/male ratio of white-collar workers increase by 1.8% (due to a 10% drop in tariffs). As for the blue-collar workers, our results are mixed, and we do not find a significant effect of tariff changes. Panel B of Figure 3 demonstrates this.

Figure 3: Chile-Mexico FTA and female employment (white- and blue-collar Workers), Chilean manufacturing firms, 1995-2007

Notes: The figure plots the evolution of the share of female white-collar employment for new Mexican exporters relative to other exporters, plotting the yearly OLS coefficients (and their 95% confidence intervals). The coefficients are the differences in the share of female white-collar workers (Panel A) and female blue-collar workers (Panel B) for exporters (new) to Mexico and other exporters. The vertical line denotes the Chile-Mexico FTA. Our yearly coefficients portray that the share of female white-collar workers before the FTA is economically small and not statistically significant, thereby indicating no differential pre-reform trends in female white-collar employment between new exporters to Mexico and other exporters.

The Free Trade Agreement increased labour productivity among firms that export to Mexico

The substitution of male with female white-collar workers had a significant impact on firms’ performance and labour productivity. Firm performance improved in terms of sales (4.8%), value-addition (4.6%), and labour productivity (14%). The increase in firms’ performance is driven not only by the adoption of new technology, but also the reorganisation of the workforce, which is in line with the findings of Hsieh et al. (2019) and Choi & Greaney (2022).

These results are driven by two major channels:

- Changes in a new exporter’s (exporting to Mexico) non-production tasks: use of technology (both domestic and foreign), innovation-related expenses, and publicity and promotional expenses (Bustos 2011, Juhn et al. 2014, and Bonfiglioli and De Pace 2021).

- A reduction or correction of discrimination in the face of pro-competitive markets. Our results show that the increase in the share of female white-collar workers is significantly higher (3-15 times) in firms which have higher proportion of males in the C-suite (both as owners and CEOs). These firms may be those with higher discrimination against women before the FTA.

Another potential mechanism which can explain the improvement in the gender gap in Chilean manufacturing firms is the supply side channel. It is possible that the new exporting firms are hiring more women because most of the available labour supply pool in Chile is women. In such a scenario, any policy change that improves the gender gap in employment in Chile could merely be due to the skewness of the sex-ratio of the population towards female in certain regions. Our evidence rules out this channel.

To test the demand-side channel, we divide our industries into export competitive (EC) and non-export-competitive (non-EC) or concentrated industries (Black & Brainerd 2004). The idea here is that the FTA opens up new trading opportunities for all industries and would expose all industries to (international) competition. However, these new opportunities would affect the non-EC industries more as they faced less competition beforehand. Therefore, if labour demand is the channel behind our observed increase in the share of white-collar workers, then we should find an increase in the relative share in non-EC industries, with little to no increase for the EC industries. We find that the increase in the share of female white-collar workers is visible across both types of industries, with higher effects for non-EC industries, thereby suggesting that the labour demand channel could be a factor in explaining the observed firm-level effects.

Trade as a policy tool for raising female labour force participation

International trade is known to influence firm level choices and thereby affect the within-firm gender gap (Black and Brainerd 2004, Bonfiglioli and De Pace 2021, Juhn et al. 2014). However, the impact can vary depending on the industries exposed to trade (Heath et al. 2024), and the underlying mechanisms behind this effect are still not well understood. Our findings demonstrate that international trade can increase female employment, specifically in white-collar jobs within the manufacturing sector. We emphasise the role of globalisation in improving labour force participation of high-skilled women, especially with soft skills.

Second, we highlight that this change in female employment is driven mainly by an increase in foreign technology adoption of the firms in the manufacturing sector. Another channel that contributes to the increase in female white-collar workers is the reduction of discrimination amongst business owners and CEOs. Therefore, new export markets or opportunities which facilitate the adoption of technology and increase the amount of skilled jobs can go a long way in reducing the gender gap in developing economies.

References

Banerjee, Utsa, Chakraborty, Pavel, and Castro Peñarrieta, Luis (2022), "Can Trade Policy Change Gender Equality? Evidence from Chile." Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4106545 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4106545.

Black, S, and E Brainerd (2004), “Importing Equality? The Impact of Globalization on Gender Discrimination,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 57(4): 540–559.

Black, S E, and A Spitz-Oener (2010), “Explaining Women’s Success: Technological Change and the Skill Content of Women’s Work,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(1): 187–194.

Bonfiglioli, A, and F De Pace (2021), “Export, Female Comparative Advantage and the Gender Wage Gap,” CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP15801.

Bustos, P (2011), “Trade Liberalization, Exports, and Technology Upgrading: Evidence on the Impact of MERCOSUR on Argentinian Firms,” American Economic Review, 101(1): 304–340.

Cortes, G M, N Jaimovich, and H E Siu (2018), “The ‘End of Men’ and Rise of Women in the High-Skilled Labor Market,” NBER Working Paper No. 24274, NBER, Massachusetts.

Eurostat (2017), “Gender Pay Gap Statistics—Statistics Explained.”

Heath, R, A Bernhardt, G Borker, A Fitzpatrick, A Keats, M McKelway, A Menzel, T Molina, and G Sharma (2024), “Female Labour Force Participation,” VoxDevLit, 11(1), February.

Goldberg, P and N Pavcnik (2018), “Integrated and Unequal?: The Effects of Trade on Inequality in Developing Countries” VoxDev.

ILO (2018), World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends for Women 2018 – Global Snapshot.

INE (2022), “Geodatos Abiertos - Lista Atlas de Género.” Available at: http://www.ine.cl/estadisticas/sociales/genero/atlas-de-genero/geodatos-abiertos-lista-atlas-de-genero. Accessed: 2022-05-04.

Juhn, C, G Ujhelyi, and C Villegas-Sanchez (2013), “Trade Liberalization and Gender Inequality,” American Economic Review P & P, 103(3): 269–273.

Juhn, C, G Ujhelyi, and C Villegas-Sanchez (2014), “Men, Women, and Machines: How Trade Impacts Gender Inequality,” Journal of Development Economics, 106: 179–193.

Lagerlof, N-P (2003), “Gender Equality and Long-Run Growth,” Journal of Economic Growth, 8: 403–426.

Melitz, M J, and D Trefler (2012), “Gains from Trade When Firms Matter,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(2): 91–118.

OECD (2011), OECD Statistics.

Trefler, D (2004), “The Long and Short of the Canada–US Free Trade Agreement,” American Economic Review, 94(4): 870–895.

World Bank (2011), World Development Report 2011: Gender Equality and Development.

World Bank and WTO (2020), Women and Trade: The Role of Trade in Promoting Gender Equality.