Autocracies and weak democracies are more likely to import facial recognition AI from China, particularly in years when they experience domestic unrest

Global economic integration has long been considered instrumental to building a liberal democratic world order (Mousseau 2003, Tabellini and Magistretti 2023). President George H.W. Bush once remarked: “No nation on Earth has discovered a way to import the world’s goods and services while stopping foreign ideas at the border.” President Bush had in mind the diffusion of democracy, in an age when democracies were the leading producers of frontier technology. However, with the emergence of China as a leading innovator in AI technologies, could greater economic integration move countries away from liberal democratic institutions? This question is particularly relevant to developing countries, many of which are institutionally fragile and which are increasingly connected with China via trade, foreign aid, loans, and investments.

In recent research (Beraja et al. 2023b), we explore the patterns and political consequences of trade in facial recognition AI technologies. Artificial intelligence (AI) technology has been hailed as the basis for a “fourth industrial revolution” (Schwab 2017) that will drive economic growth in the years to come (Bughin, and Hazan 2017, Aghion et al. 2018, Brynjolfsson et al. 2021). But the technology has also brought new challenges to the fore. It might undermine democracies (Acemoglu 2021a, 2021b), enhance autocrats’ aims of social control (Guriev and Treisman 2019, Tirole 2021), and empower “surveillance capitalists” (Zuboff 2019). China, in particular, has used facial recognition AI as a key technology to support its surveillance state (Beraja et al. 2023a).

Tracking global trade in facial recognition AI

We begin our paper by constructing a database on global trade in facial recognition AI. We collect data on trade in facial recognition AI from 2008 to 2021 by combining AI trade deals listed in the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s report The Global Expansion of AI Surveillance (Feldstein, 2019) with our own search of AI trade deals from all facial recognition AI firms in the Capital IQ database. In total, we find 1,636 AI deals from 36 exporting countries to 136 importing countries. From this dataset, we document three facts.

China has a comparative advantage in facial recognition AI

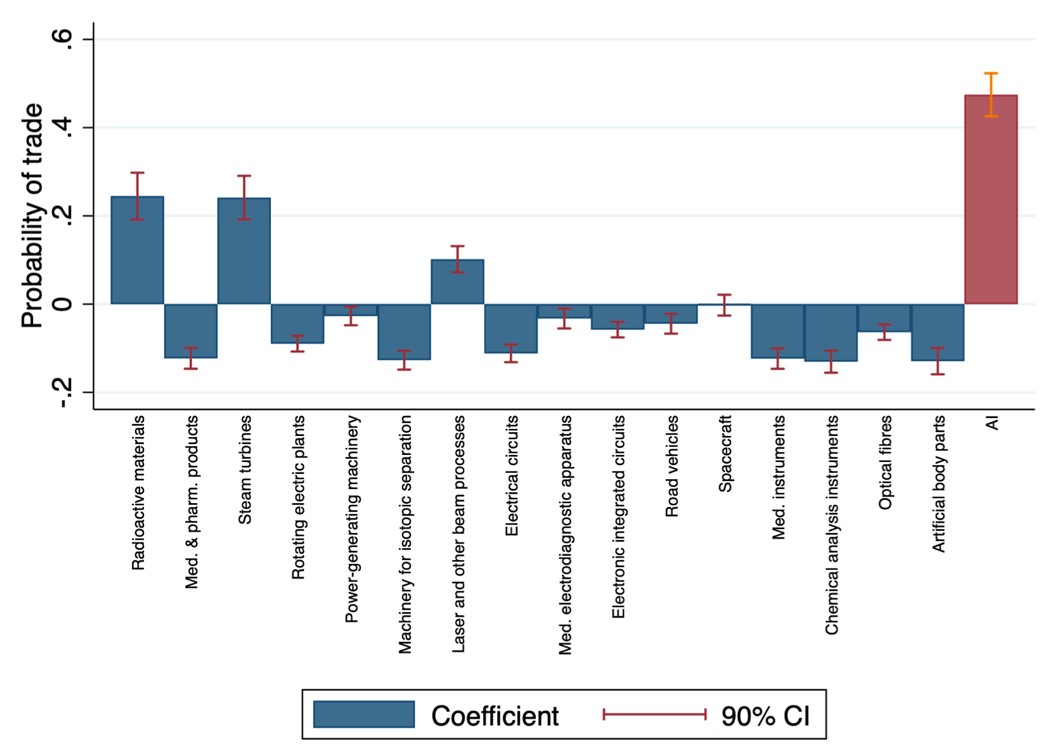

First, China has a comparative advantage in facial recognition AI. In Figure 1, we plot trade flows for the two largest exporters of facial recognition AI, China and the US. China exports to roughly twice as many countries as the US (83 versus 57 links) and has about 10% more trade deals (238 versus 211). To test China’s comparative advantage more rigorously, we compare whether China is more likely to export facial recognition AI relative to other kinds of frontier technology. In Figure 2, we plot China’s probability of trading each kind of frontier technology, relative to other countries and technologies. We see that while China displays a comparative advantage in radioactive materials, steam turbines, and laser and other beam processes, China’s largest comparative advantage is in facial recognition AI. Different factors may have contributed to this fact: the Chinese regime has explicitly made becoming a world leader in AI one of their key development and strategic goals, and the facial recognition AI industry has benefited from the government’s own demand for surveillance technology, often receiving access to large-scale government datasets (Beraja et al. 2023c).

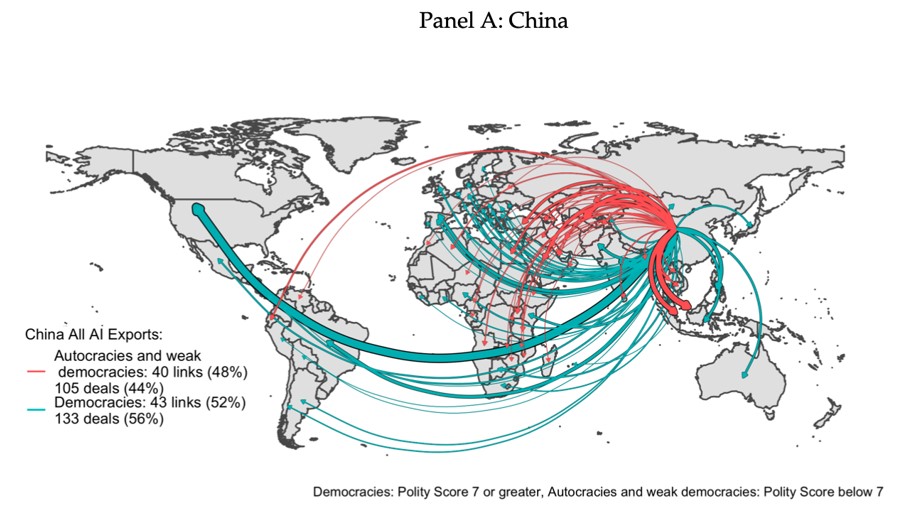

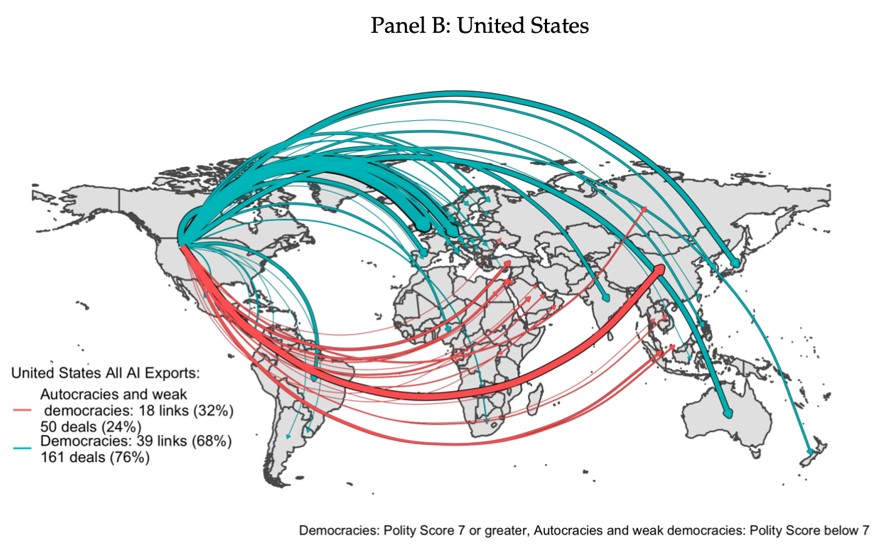

Figure 1: Surveillance AI exports from China and the US.

Figure 2: China’s probability of trade, compared against the rest of the world and other frontier technology exports.

Autocracies and weak democracies are more likely to import facial recognition AI from China

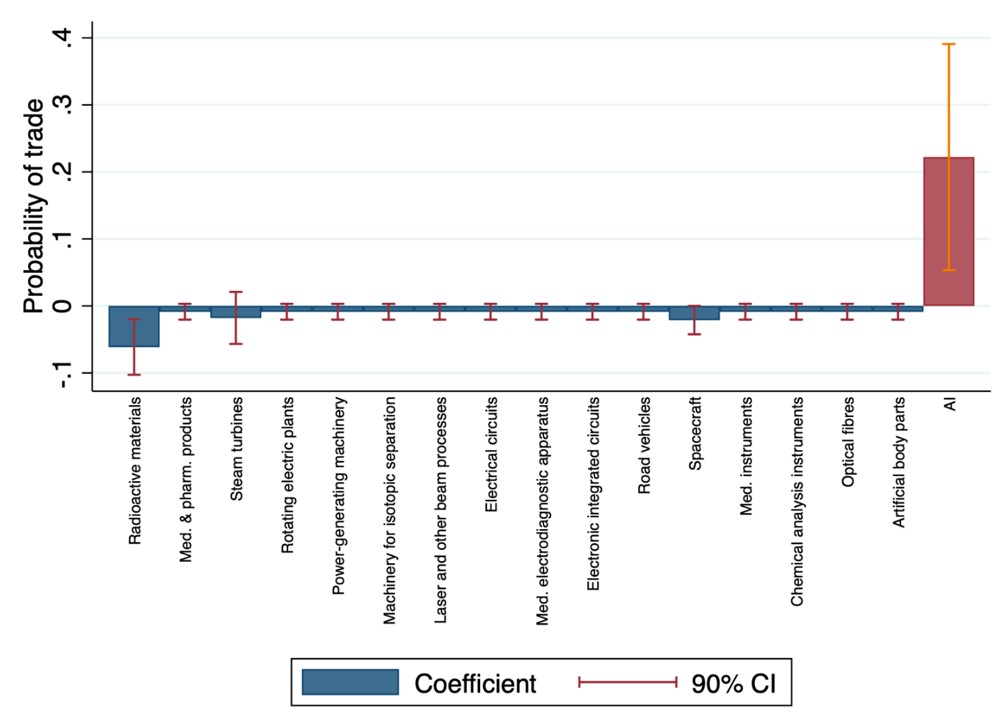

Second, we find that autocracies and weak democracies are more likely to import facial recognition AI from China. In Figure 3, we reproduce Figure 1, now breaking up trade flows by whether the destination country is an autocracy/weak democracy or mature democracy. While the US predominantly exports facial recognition AI to mature democracies (roughly two-thirds of its links, or three-quarters of its deals), China exports roughly equal amounts to mature democracies and autocracies or weak democracies. Might this just be because China exports more to autocracies and weak democracies across all products? We formally test for China’s autocratic bias in exporting facial recognition AI by comparing it against China’s exports of other frontier technologies. In Figure 4, we show that this is not the case. Facial recognition AI is the only technology for which China displays this political bias. Notably, we do not find any such bias when investigating the US. One potential explanation for this fact is that autocracies and weak democracies might specifically turn to China for AI technology used for social and political control. We explore this possibility in greater depth in our last fact.

Figure 3: Surveillance AI exports from China and the US, split by destination regime type.

Figure 4: Political bias in frontier technology exports from China.

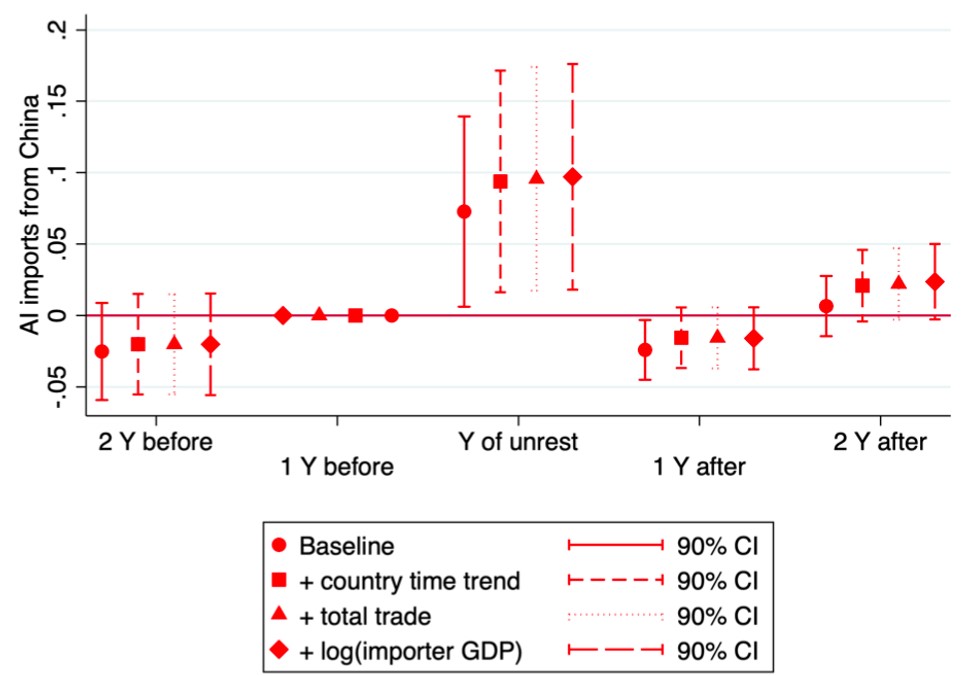

Autocracies and weak democracies are more likely to import facial recognition AI from China in years when they experience domestic unrest

Third, we show that autocracies and weak democracies are more likely to import facial recognition AI from China in years when they experience domestic unrest. We focus our analysis on weak democracies and autocracies and examine when they tend to import facial recognition AI from China, relative to times when they experience high levels of social and political unrest. In Figure 5, we show that surveillance AI is imported during the year of unrest, and not pre-emptively (before unrest occurs) or following unrest. This pattern holds when we focus attention on only “smart city” AI trade deals that are most likely associated with mass surveillance (the two prior facts also hold when looking at this subset of deals). However, we do not find that mature democracies import more facial recognition AI in response to unrest; we also do not find that autocracies and weak democracies import more facial recognition AI from the US in response to unrest.

Figure 5: Event study, local unrest in autocracies and weak democracies on surveillance AI imports from China (different symbols present estimates from models including different sets of control variables)

Does importing surveillance AI technology accompany broader institutional changes?

Finally, we examine whether imports of surveillance AI technology during periods of domestic unrest are concomitant with broad changes in domestic institutional quality in autocracies and weak democracies. We show that Chinese surveillance AI imported during episodes of domestic unrest are associated with a country’s elections becoming less fair, less peaceful, and overall of lower quality. This pattern appears to also hold with imports of US surveillance AI, although it is less precisely estimated. In contrast, we do not find any association between surveillance AI imports and electoral institutional quality among mature democracies. Rather than interpreting our findings as the causal impact of AI on institutions, we think of the import of surveillance AI and the erosion of domestic institutions in autocracies and weak democracies as the joint outcome of a regime desiring greater political control. Interestingly, we find that imports of military technology follow a similar pattern to surveillance AI during periods of unrest. We also find suggestive evidence that autocracies and weak democracies importing large amounts of Chinese surveillance AI during unrest are less likely to transition to mature democracies when compared to their peers that import low amounts of surveillance AI. On the whole, these results suggest that the broad set of tactics employed by autocracies during times of unrest—importing surveillance AI, eroding electoral institutions, and importing military technology—may entrench non-democratic regimes.

Policy implications

Our research reveals that trade may not always foster democracy and liberalise regimes. In particular, China’s greater integration with the developing world may yield undesirable political consequences, suggesting the need for AI trade regulation. Regulation of surveillance AI can be modeled on regulation of other goods that produce similar negative externalities. Autocratically biased AI may be trained on data collected for politically repressive purposes, similar to goods produced from unethically sourced inputs, such as child labour. Surveillance AI may also have negative downstream global externalities, such as lost civil liberties and political rights, similar to pollution. Finally, like dual-use technologies, facial recognition AI has the capacity to benefit consumers and firms, but may cause harm when deployed for the wrong purposes. Altogether, these features suggest that trade regulations must be carefully devised to ensure that frontier AI technology can diffuse around the world, without also supporting the diffusion of autocracy.

References

Acemoglu, D (2021a), “Harms of AI,” Oxford Handbook of AI Governance, forthcoming.

Acemoglu, D (2021b), “Dangers of unregulated artificial intelligence,” VoxEU.

Aghion, P, B F Jones, and C I Jones (2018), "Artificial intelligence and economic growth." In The Economics of Artificial Intelligence: An Agenda, pp. 237-282. University of Chicago Press, 2018.

Beraja, M, A Kao, D Y Yang, and N Yuchtman (2023), "AI-tocracy." Quarterly Journal of Economics, 138(3): 1349-1402.

Beraja, M, A Kao, Y D Yang, and N Yuchtman (2023), "Exporting the Surveillance State via Trade in AI." NBER working paper.

Beraja, M, A Kao, Y D Yang, and N Yuchtman (2023), "Data-intensive Innovation and the State: Evidence from AI Firms in China." Review of Economic Studies, 90(4): 1701-1723.

Brynjolfsson, R, D Rock, and C Syverson (2021), “The Productivity J- Curve: How Intangibles Complement General Purpose Technologies," American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 13(1): 333-72.

Bughin, J and E Hazan (2017), “The new spring of artificial intelligence: A few early economies,” VoxEU.

Feldstein, S (2019), The Global Expansion of AI Surveillance (Vol. 17). Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Guriev, S, and D Treisman (2019), "Informational Autocrats." Journal of Economic Perspectives 33(4): 100-127.

Schwab, K (2016), The Fourth Industrial Revolution. New York: Crown Business.

Mousseau, M (2003), "The Nexus of Market Society, Liberal Preferences, and Democratic Peace: Interdisciplinary Theory and Evidence." International Studies Quarterly, 47(4): 483–510.

Magistretti, G and M Tabellini (2023), "Economic integration and democracy: An empirical investigation." Working paper.

Tirole, J (2021), “Digital Dystopia,” American Economic Review, 111(6): 2007-2048.

Zuboff, S (2019), The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs.