In Mexico, where formal jobs have low starting salaries which increase rapidly over time, temporary wage subsidies to young high school graduates lead to sustained formal employment gains

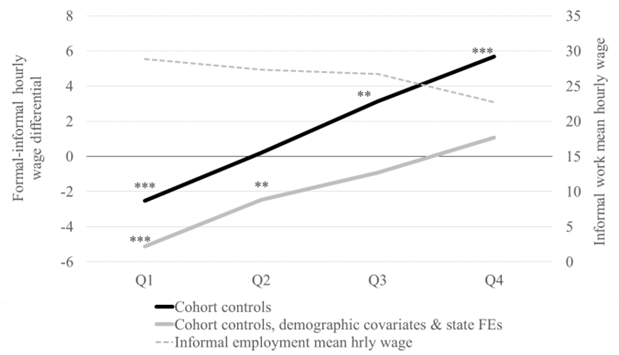

In many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), young people face different employment paths when entering the labour market. Among the most important decisions is whether to start their career in the formal or in the informal sector. Informal sector jobs are often easier to obtain and may offer advantages such as shorter commuting times and more flexibility compared to formal employment. They also offer relatively high starting hourly pay for low-skilled labour market entrants. Indeed, in Mexico, entry-level hourly wages for low-skilled youths aged 17 to 20 are 9% to 17% lower in the formal than in the informal sector (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Wage differentials between formal and informal work

Notes: Source: National-level panel data from ENOE 2016-2019. Standard errors are robust, *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Graphs depict trajectories of hourly wage differentials across youth employment spells. Hourly wages are in pesos. Sample limited to youth aged 17-20 starting a new employment spell and with positive wages.

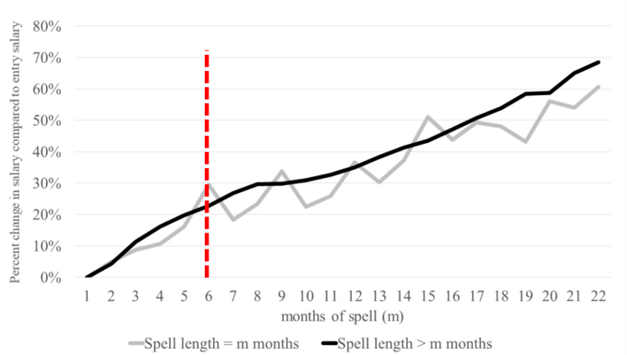

Therefore, youths may choose informal employment as their entry-point into the labour market, especially if they are focused on short-term benefits. This choice can have long-term adverse effects as informal work offers relatively constant wages and only rarely presents a steppingstone to formal work (Levy 2010 ILO 2015). By contrast, formal wages grow substantially by about 25% (35%) over the first six (twelve) months on the job (Figure 2), in addition to other benefits such as coverage by social security programs.

Figure 2: Formal sector wage growth

Notes: Administrative data from the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS), June 2019-May 2021. Graph depicts mean percent salary change from formal employment over time (capturing 1005 employment spells). The grey line shows the average wage gain for workers who leave after exactly m months.

Our study

To address the initial (wage) disincentive of formal work, in partnership with the Mexican government, we designed and tested an employment incentive that pays recent secondary school graduates the equivalent of about 20% of the average formal entry level wage, for up to six months, if they hold a formal job (Abel et al. 2022). In contrast to similar programs tested in LMICs, which tend to find modest results (McKenzie 2017), the program circumvents employers and pays incentives directly to workers.

We conducted a study with a sample of almost 2,000 graduating students across vocational and general education tracks from 13 upper secondary schools in the San Luis Potosi metropolitan region. We randomly assigned half of the graduating students in each school to be eligible for the wage incentive and test its effect on employment outcomes over two years (starting in June 2019) combining survey and high-frequency social security data. Employers in our study area face high turnover and struggle to fill positions. While the study was not designed to measure displacement effects, they tend to be less pronounced in these tight labour markets (Crepon et al. 2013).

Does this incentive work?

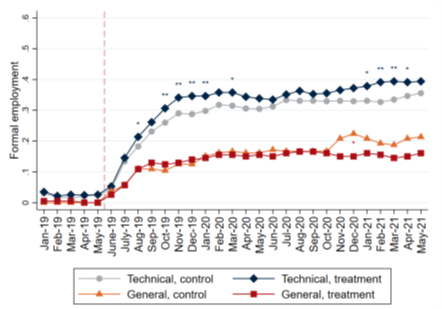

The incentive increased formal employment among eligible vocational school graduates by 4.2 percentage points (14.5 percent) over the first two years, driven by a 5 percentage point (25 percent) increase in jobs with permanent contracts (Figure 3). Formal employment gains are due to both extensive and intensive margin effects. On the extensive margin, the incentive increases the share that ever holds a formal (permanent) job by 10% (21%). About half of this effect comes from a reduction in informal employment. On the intensive margin, the incentive increases retention rates among workers starting with temporary contracts. For those in the treatment group, the hazard rate of leaving employment is 26% lower, and they are 70% more likely to transition to a permanent contract.

In contrast, no effects are found among graduates of general schools, which aim to prepare students to pursue further education – an important finding for policymakers who are concerned about unintended consequences on school leavers' decisions to pursue or complete further education.

Figure 3: Employment impacts of wage bonus treatment, by school type. (a) Share with formal work (b) Share with permanent contract

Notes: Source: Administrative data from the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS), June 2019-May 2021. The vertical dotted line indicates the time of graduation when participants started to be eligible for the wage incentive.

The documented shifts in employment types matter as formal jobs, especially those with permanent contracts, lead to an accumulation of human capital that benefits workers. Importantly, we find that when workers switch formal jobs, even involuntarily, they do not experience a drop in wages, suggesting that the skills workers learn on the job are not firm-specific (Becker 1964). Especially in LMICs where youth turnover rates are high (Donovan et al. 2020), obtaining general skills is important for helping workers maintain positive wage growth, even as they transition between firms.

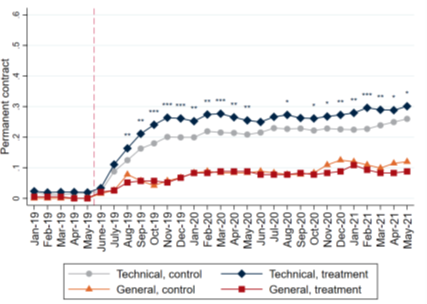

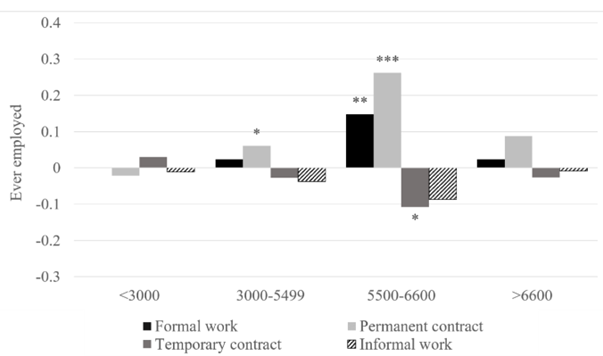

Treatment effects are concentrated among youths with reservation wages just above formal sector starting wages (Figure 4). High reservation wages (the lowest wage level for which a job seeker would be willing to accept a job) may help explain why youths do not pursue careers that are more stable and lucrative in the long-run but offer low starting wages.

Figure 4: Incentive impacts by baseline reservation wage

Notes: Sources: Endline surveys and administrative data from the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS), June 2019-May 2021. Graphs depict treatment coefficients for youth by subgroup of self-reported reservation wage at baseline; no control variables included in regression. Reservation wages are monthly in pesos. N-sizes for baseline-reported reservation wages are as follow: 542 youth reported below $3000, 823 youth reported $3000-$5499, 200 youth reported $5500-$6000, 359 youth reported over $6600. Standard errors are robust, *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

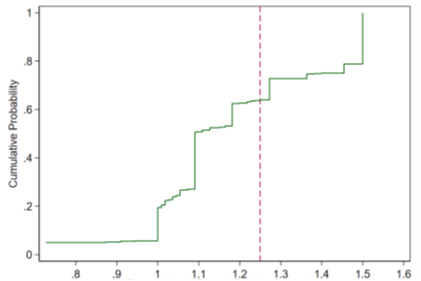

This raises the question of why job seekers set high reservation wages and search little for jobs in the formal sector relative to the informal sector. For one, we find that young individuals tend to significantly underestimate formal wage growth (Figure 5). Moreover, similar to patterns observed in other countries (Harrison et al. 2002), youth in our sample have very high discount rates, which limits the attractiveness of future benefits that (formal) jobs offer including strong wage growth and social protection coverage. Thus, providing information about benefits of formal employment may not be sufficient to dampen reservation wages if youths heavily discount the future.

Figure 5: Beliefs formal sector wage growth (6 months)

Notes: Source: Endline Survey. The graph shows the cumulative probability distribution of the perceived growth in formal jobs over a six months period. The dotted line shows the actual growth rate of about 25% computed with IMSS data. The majority of participants substantially underestimate formal sector wage growth: 20% believe that there is no wage growth and the median belief is less than 10%.

Immediate incentives such as our wage supplement circumvent these problems, effectively lowering reservation wages and nudging youths towards accepting initially lower-paying formal jobs. So, why don’t firms just pay them more in the beginning? The acquisition of general skills helps explain why firms do not pay starting wages that are (temporarily) above workers' productivity levels, as they may be poached by other firms at later points in time when firms need to pay below their marginal productivity in order to compensate initial losses.

Implications for policy

Our wage incentive experiment effectively increases workers' return to accepting formal employment thus providing insights into an important debate about how the tax implicit in the design of social security and social protection systems affects formal sector labour supply (Packard et al. 2019). Social security deductions on wage income act like a tax on formal employment while non-contributory social protection programs act like a subsidy to informal employment, widening the gap between the marginal product of formal and informal labour. For low-skilled workers in Mexico the implicit tax-cum-subsidy is estimated to be in the order of 34% (Levy 2010).

It has been argued that this wedge may contribute to an oversized informal sector, which workers enter in part by choice (Levy and Cruces 2021, Perry et al. 2007). Lowering these deductions would raise the net pay for formal workers. Our experimental results suggest that a 20% increase in (starting) wages paid to workers increases formal employment by about 4 percentage points or 10%, which implies a labour supply elasticity of around 0.5 at the level of formal sector starting wages. For permanent formal employment, the elasticity is around 1.2, suggesting that a reduction in this tax-cum-subsidy would have sizeable effects for low-skilled youths in Mexico.

References:

Abel, M, E Carranza, K Geronimo, M E Ortega (2022), “Can Temporary Wage Incentives Increase Formal Employment? Experimental Evidence from Mexico”, Policy Research Paper WPS 10234. The World Bank.

Becker, G S (1964), “Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education”, University of Chicago Press.

Crepon, B, E Duflo, M Gurgand, R Rathelot, and P Zamora (2013), “Do labor market policies have displacement effects? Evidence from a clustered randomized experiment.", Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128: 531-580.

Donovan, K, W J Lu, T Schoellman (2020), “Labor market dynamics and development”, Discussion Papers. 1079. Yale University.

Harrison, G W, M I Lau and M B Williams (2002), “Estimating individual discount rates in Denmark: A field experiment.”, American Economic Review, 92(5): 1606-1617.

ILO (2015), “Promoting Formal Employment Among Youth: Innovative Experiences in Latin America and the Caribbean”.

Levy, S (2010), “Good Intentions, Bad Outcomes: Social Policy, Informality, and Economic Growth in Mexico”, Brookings Institution Press.

Levy, S and G Cruces (2021), “Time for a New Course: An Essay on Social Protection and Growth in Latin America”, UNDP LAC Working Paper.

McKenzie, D (2017), “How effective are active labor market policies in developing countries? a critical review of recent evidence.”, The World Bank Research Observer, 32(2): 127-154.

Packard, T, U Gentilini, M Grosh, P O'Keefe, R Palacios, D Robalino, and I Santos (2019), “Protecting All: Risk Sharing for a Diverse and Diversifying World of Work”, The World Bank.

Perry, G, W F Maloney, O Arias, P Fajnzylber, A Mason, and J Saavedra-Chanduvi (2007), “Informality: Exit and Exclusion”, The World Bank.